An internationally renowned contemporary artist and a professor of neuropsychology peered into their own brains yesterday, to see if they could identify what made them different.

Richard Wentworth, the artist, and Richard Gregory, emeritus professor of neuropsychology at Bristol University, discovered they had more in common than their first names. As boys they took carpentry classes on Saturdays: but if this was influenced by any part of their brains, neither could spot it, until yesterday.

No one had compared the brains of scientists and artists until then. Research has suggested differences in the brains of musicians and mathematicians, and one study found changes in brain function in taxi drivers before and after they did the Knowledge - suggesting that sections of the brain work like muscles, and can grow.

Both men volunteered to go through a CAT scanner in a London hospital, as part of Head On, a Science Week exhibition opening at the Science Museum in London on Friday, which looks at the links between art, science and the brain.

The scientist described the experience as feeling like being a cross between Tutenkhamun's mummy and a space man; the artist said it was "like being in the top bunk of a P&O ferry to France".

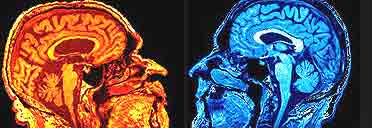

The scans, brilliantly coloured to reveal all the brain structures, fascinated them.

"They are jolly different, aren't they?" said Professor Gregory. "I've ordered thousands of scans in my career, but it's a very strange feeling to be looking at an image of my own brain."

Mark Lythgoe, of Great Ormond Street Hospital, who did the scans, believes significant differences will be discovered in the way the brains of scientists and artists work, but warned that no deductions were possible on a sample of two.

The only safe instant conclusion was that one was the brain of a much older man.

Prof Gregory, 78, looked slightly downcast; 55-year-old Mr Wentworth looked smug.

Another scientist, Lewis Wolpert, dismissed the experiment as trivialising, and insisted scientists and artists were so different it would make more sense to compare rugby and billiards on the basis that both were played with a ball.

Both men leapt on the allusion. The artist said how fascinating it would be to try billiards with an oval ball, the scientist announced that he had built an elliptical snooker table.

Mr Wentworth stared at the two scans. "I think it's like hav ing an A to Z and a Nicholson's guide to London - the places are the same, but the ways you get there are different."

The experiment left Prof Gregory with an emotion which has inspired art for thousands of years: intimations of human mortality.