My mother has always been up-front about the fact that when she learned she was pregnant with my older brother she flew into a rage. She had been married to my father for only a month. After one of those rare 1950s weddings between bona fide virgins, she had barely sampled the pleasures that legitimacy afforded, and three was a crowd. Her spitting indignation at the doctor's office became the stuff of family myth, often related with a comic, cheerful cast. Whether knowledge that his arrival was unwelcome later contributed to my older brother's ... um ... difficult character I couldn't say, though it may not have helped.

Given my mother's - let's use a gentle word - ambivalence over her own first pregnancy, it is little wonder that she took me aside when I was in my mid-30s, and had just fallen in love. She warned me that if we decided to have a child, motherhood would "completely transform" my relationship. Though she did not spell it out, there was no question that she meant for the worse.

I am struck by my mother's candour. Nowadays, for a mother to openly allow that her offspring was an unwanted intrusion into her marriage would probably be considered child abuse. My mother would be expected to shut it, to bury her real feelings and concoct something nauseously rosy instead. Indeed, one of the things that has put me off having children is motherhood's unwritten gag law. While we may have taken the lid off sex, it is still out of bounds to say that you do not like your own kids, that the sacrifices they have demanded are unbearable, or that, perish the thought, you wish you had never had them.

As it happened, my mother's cautions were unnecessary. I have been ambivalent about motherhood - or more honestly, hostile to it - from about the age of eight. I did not even engage with the issue until my early 40s, when I wrote We Need To Talk About Kevin, a novel that examines what it might be like for motherhood to go fatally, catastrophically wrong.

Much to my surprise, after six of my previous novels had sold modestly at best, Kevin has created a stir in the US, and was selected by ABC's Good Morning America television book club. The novel has already prompted a strong response in the UK as well, having recently been chosen for BBC1's book programme Page Turners, to be broadcast in April. Of course, I like to fancy that the novel is nicely written. But the reason for the unlikely popularity of this rather dark book must go deeper than that.

I think Kevin has attracted an audience because my narrator, Eva, allows herself to say all those things that mothers are not supposed to say. She experiences pregnancy as an invasion. When her newborn son is first set on her breast, she is not overwhelmed with unconditional love; to her own horror, she feels nothing. She imputes to her perpetually screaming infant a devious intention to divide and conquer her marriage. Eva finds caring for a toddler dull, and is less than entranced by drilling the unnervingly affectless, obstreperous boy with the ABC song. Worst of all, Eva detects in Kevin a malign streak that moves her to dislike him. Her misgivings seem well founded when, at the age of 15, he murders nine people at his high school. Whether Kevin was innately twisted or was mangled by his mother's coldness is a question with which the novel struggles, but which it ultimately fails to answer. That verdict is the reader's job.

Though some readers have been put off by my narrator's unattractive confessions, a remarkable number of people have expressed to me their gratitude that someone in modern literature has put motherhood's hitherto off-limits emotions into print. Novels routinely portray children as adorable moppets who pop up with wisdom beyond their years at the dinner table. Oh, they may get a little fussy, but any less than charming behaviour is never their fault: they need a nap, or their parents are getting a divorce.

This perfumed and blameless version of childhood does not comport with my memory of being a kid (my brother was not the only one who was difficult), nor with the real-life tearaways whom I encounter in the supermarket. And surely the obnoxious, demanding, shrill and vicious children to whom I give wide berth in the baked-goods aisle are not all, to their parents, ceaselessly sweet darlings whose company affords only joy and celebration of new life.

But that gag law ensures that if their parents do go through periods of disliking their own children, they will not say so, not to anyone. One of the reasons that mothers enter into a pact to be sunny come what may is that they live in terror that some careless slip or angry explosion will damn their poor urchins for all time, which is why my mother's honesty about her first pregnancy would be less likely a generation later. Modern-day mothers get stuck with virtually blanket responsibility for how their kids turn out.

How we came to conceive of children as passive objects upon which adults act is beyond me. From my earliest years, I remember being a conscious agent. I knew when I was not supposed to do something, and sometimes I did it anyway.

A random example? When I was 10, my father had given my mother a Russell Stovers assortment box for her birthday, and after a Sunday lunch my mother offered each of us kids one chocolate. But we weren't allowed to pick the cream-filled sort (the round ones), which were her favourites, only a caramel (the squares). But I preferred the cream-filled kind, too. I flew into a tantrum. I screamed. I wailed. I flopped about the floor.

The point of this anecdote is not that I was the pettiest kid imaginable (though maybe I was). The point is, I knew full well that they were my mother's chocolates, and I was lucky to get a caramel. I knew that I was ruining everyone's afternoon. I knew that whether I got a cream or a caramel didn't matter that much, even to me. I knew that I had no call to fly into a fit, and I screeched my head off anyway. (To my parents' credit, not only was I rewarded with no chocolate at all, but before sending me to my room, they laughed at me. I commend the gambit. At 47, I still feel ashamed of myself.)

When I have pressed proponents of kid-as-pure-victim to consider whether they, too, experienced an ongoing sense of volition as children, they often frown. Hmm, they reflect. Yes, actually. Why is this such a revelation? Weren't we all kids once? And was everything disagreeable we did because we were abused, neglected, or traumatised by divorce? I did not want a caramel. I wanted a cream! I was a perfect horror that afternoon, and that discreditable tantrum was all my fault - I don't care that I was only 10.

Yet while researching Kevin I came across multiple studies and editorials that placed the blame for American school shootings firmly on the parental doorstep. My own reading failed to substantiate that most shooters suffered in any exceptional sense; after all, life is hard, and somewhere along the line we are all abused, if you loosen the definition enough. Nevertheless, countless sociologists have strained to explain the phenomenon in a way that turns the culprits into victims. Like my character Eva, several parents of these killers have been sued by the families of murdered children for parental negligence.

The contemporary parent-child model seems to be a whitewash at both ends. Parents can't confess to even passing dislike for their kids, much less can they entertain regrets. And kids are innocents, any of whose atrocious behaviour can be traced back to a parent's original sin. Since both constructs are lies - the happy-happy parent, the purely reactive child - this rigid archetype is a formula for artifice, misunderstanding and, in some cases, disaster.

Although my narrator in Kevin may be painfully candid with the reader, she was dishonest throughout her son's upbringing. Eva went through all the right motions; she baked biscuits. But she was meanwhile stifling a host of furies and resentments, and her son could tell. Ironically, it is only after Kevin has done the unthinkable that all pretence is stripped away.

So I would rather know how my mother really reacted to her first pregnancy than be fed acceptable but fraudulent claptrap about how delighted she was, and I wager that even my older brother would prefer the truth as well. Parents are people too, and their emotions are sometimes going to depart from script. Moreover, children are people too, which means that to give them at least partial responsibility for how they turn out, and for whether they murder their classmates, is to take them seriously as fully human.

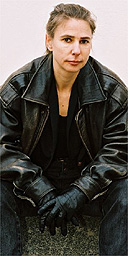

· We Need To Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver is published on March 1 by Serpent's Tail