Twelve of them were waiting patiently for the medical students. On the trolleys beneath their blue plastic sheets they had all the time in the world and nowhere particular to go except the next one.

But, as cadavers in Keele University's new medical school, they had a valued place in educating tomorrow's doctors - and if they provoked their share of macabre humour, they're immune to it now. How else have young doctors always come to terms with death? There are mannequins costing £5,000-plus and a lot of the latest digital doodahs, but they still need dead bodies to cut up and learn on.

No, I didn't really want to see one of the corpses, I told Hayley Derricott, a prosector in anatomy, with a delightful line in black humour, who was showing me round the anatomy lab.

What I didn't tell her was that my father had died a year ago that day and I was suddenly flooded with memories of talking to his corpse laid out in the undertaker's coffin and deciding that no, he wasn't going to wake up like the time that, as kids, we buried him on the beach at Dunbar.

What hadn't occurred to me or my siblings was to pack him off to the nearest medical school to entertain and educate the students, which in retrospect seems a bit of a waste. After a lifetime in teaching it might have been a fitting part of his afterlife. Yes, I could see him quite happily under a blue sheet on a trolley - perhaps that's why I was not keen to let Derricott unveil one of her charges for me.

New company always perked him up, especially young women, so being the centre of attention and some good banter might not have been such a bad next stage.

Certainly medical schools need all the stiffs they can get.

Last week the British Medical Association's annual conference in Belfast passed a motion of concern over the decline in donations, calling on UK Transplant, the organisation that supports transplantation services, to launch a campaign to encourage whole body donation. At present the website (www.uktransplant.org.uk) allows you to register to donate only your kidneys and corneas and so on.

Over the past five years the number of people in England and Wales leaving their bodies to medical education and research has fallen from 670 to 600. At the same time, the advent of eight new medical schools and the expansion of existing ones means 6,000 students being trained, and 15 new postgraduate anatomy departments have opened to improve the training of surgeons. The situation is so serious that the chief medical officer, Sir Liam Donaldson, earlier this year urged all doctors to encourage their patients to sign up to bequeath their bodies to their nearest medical school.

Mike Mahon, director of anatomy at Keele, says about 1,000 bodies a year are needed nationally. But while an established medical school like Manchester, where he worked for 25 years, has built up a list of up to 10,000 donors, the position is more acute for a new school like Keele, which has to build up a local clientele.

The public doesn't distinguish between anatomy - strictly controlled since 1832 by a law to stop bodysnatchers - and pathology. Donations fell following the discovery that body parts had been retained without consent by the pathology departments at Bristol children's hospital and Alder Hay hospital in Liverpool.

Donations - or "bequeathals" as they are quaintly termed - fell further after the lurid Channel 4 series Anatomy for Beginners, featuring Gunther von Hagens. The Department of Health said intending donors cited these as prompting them to withdraw.

The Human Tissue Act 2004, which comes into force in September, should clarify the legal position on using body parts for research, but it is also stricter in requiring the written and witnessed consent of the donor.

Mahon says plenty of people say: "I've always wanted to donate my body, but I don't know how to go about it." Quite a few women inquire about their husbands, he notes. Men tend to be less organised.

It's not made particularly easy. It's simple to register online at UK Transplant but that is only for organs. Not everyone thinks to approach their local medical school, even if they know which it is. There is a national Department of Health number you can ring and leave a message - probably feeling rather self-conscious. Followed, in my case, with a brisk but friendly phone call asking for an address. They post a form for your local teaching hospital. Simple if you know about the number.

Providing the paperwork is in order - a copy with the medical school and one with your solicitor or a relative - things have to move fairly quickly as you have to be embalmed and refrigerated within three days to be at your best for the next three years, the period a medical school can retain your posthumous services. The medical school takes care of the arrangements and sends undertakers to collect.

It will also arrange (and pay for) a funeral and/or cremation for your (re-collected) remains if that is what your family wants.

With permission of the next of kin, body parts may be retained for longer. A particularly interesting heart, for instance, might be seen by thousands of students over the years in the lab, says Mahon.

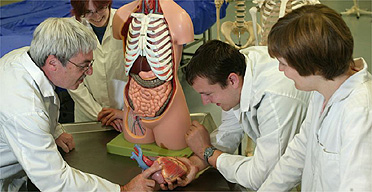

It's this individuality that mannequins or computer modelling cannot give the students. Groups of students work on dissecting a dozen bodies in the lab at Keele. "The most interesting things are the differences from body to body - one has a coronary artery across the front of the heart, another has two branches. They get a feel for solid lumps and soft tissue, for a cist or stones in kidneys. They don't get a surprise when they do surgical work later and find there is so much variation from person to person. Without a cadaver they don't get the three dimensional aspects and the texture and variation," says Mahon.

Students are reticent at first, he says, but soon become rather proprietorial about "their" body. American medical schools talk a lot about bereavement. "We don't run courses on it, we just get on with the practical work to be done," says Mahon.

Not every corpse makes the grade when it comes to medical school. If a coroner's post mortem has been carried out, you're not much use and you won't be accepted with hepatitis or dementia in case of infection. Cadavers at Keele range from 52 to 99 years old, but the average age is mid-70s. No under 18s are eligible.

What would my father have felt about it? We never discussed funerals or his mortal remains, he being a man who cheerfully followed the biblical injunction to take no thought for the morrow, even when it drove his loved ones berserk.

The nearest he and I got was a jokey reference to Browning's wicked renaissance bishop ordering his tomb in St Praxed's church surrounded by his bastards.

But, unlike the bishop who looted a huge piece of lapis lazuli - "blue as the vein o'er the Madonna's breast" - for a decent tomb in his church, I wouldn't mind making do with a blue plastic post-mortem covering and the company of students. I intend to steer clear of hepatitis, dementia and violent death - but to keep those medics waiting a bit longer.

· To donate your body to medical education contact HMIA, Wellington House, 133-155 Waterloo Road, London SE1 8UG; 020 7972 4342