It has been argued that human beings love the water because we evolved from a species of aquatic ape, but if you look at the state of Britain's swimming pools, you wonder if we're now heading in the opposite direction. Having spent the past few centuries developing ever more sophisticated monuments to aquatic recreation, swimming pool architecture seems to be in a state of regression. The scenario today's swimmers are most likely to experience is a lukewarm bath of chemicals and urine in a humid 1970s leisure centre - possibly the closest mankind has come to recreating the primordial soup.

Swimming architecture in Britain reached its evolutionary peak in the 1930s and 40s. This was the golden age of the lido, an era to which older swimmers look back with nostalgia and younger ones with envy. The word itself (derived from the bathing resort just off Venice) conjures images of something more exotic than a utilitarian swimming pool ("machines for swimming in", as Iris Murdoch, who preferred rivers, described them). The prospect of being able to swim outdoors, lie in the sun and generally reconnect with our inner aquatic ape was appealing enough to interwar Britons, but lidos were also places to commune. They were an environment outside the ordinary rules of society, where physiques could be safely displayed and appraised, and where the mixing of the gene pool was a distinct possibility.

Package holidays, council cutbacks and maintenance headaches have all added to the demise of the British lido, and out of the 300-odd lidos and outdoor pools in operation before the second world war, only about 100 are still open. But the functions they fulfilled can hardly be said to have gone out of fashion, and in recent years a growing grassroots community - including architectural conservationists, hardcore bathers and ecologically responsible leisure-seekers - has mobilised to stop the lido going the way of the dodo.

And they've been making considerable progress. A number of derelict lidos around the country have been successfully reinstated in recent years, such as those in Plymouth, Penzance and Brighton. Others, in Uxbridge, Brockwell Park, Broomhill in Ipswich, have been brought back from the brink of extinction, thanks to new refurbishment contracts. Putatively leading the current renaissance is Hackney's London Fields Lido, which closed in 1984 and has been undergoing a £3m renovation. As well as restoring the facility to its former glory, the scheme aims to put a removable roof over the pool, to allow for winter swimming. But although the lido was due to re-open this month, the date has now been put back till October - due, among other things, to the discovery of large quantities of asbestos in the buildings.

As much as some lido lobbyists would like to see every pool restored to its prime, the London Fields Lido serves as a reminder that most lidos were not necessarily built to last. Lidos were very much an early 20th-century craze, and as a result they were frequently thrown up quickly, using cheap labour, in the interests of political gain. Most were built by local authorities, and overseen by engineers rather than architects. Consequently, their styles vary wildly, as Janet Smith's comprehensive book Liquid Assets, published by English Heritage, attests. Some look like adapted cricket pavilions, others like neo-classical temples or art deco palaces.

But above all, lidos were a place where racy new European modernism found a safe haven. Mendelsohn and Chermayeff's celebrated De La Warr Pavilion, in Bexhill-on-Sea, introduced Britain to seaside modernism in 1935, and its nautical influence is clearly visible in Brighton's Saltdean Lido, with its flat roofs, curvilinear facades and ship-like railings, built three years later.

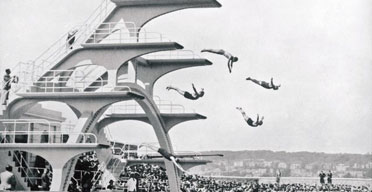

Lidos produced other striking structures, not least Weston-super-Mare's diving platform. An evocative, extravagant tower built upon two reinforced concrete arches, its swooping lines and slender cantilevers somehow summed up the spirit of the age, but it was demolished in 1982. In London, architects Rowbotham and Smithson produced a run of handsome deco lidos typically composed of harmoniously proportioned brick boxes, which could almost have come off the drawing board of Frank Lloyd Wright. Many are still running, including those at Brockwell Park and Parliament Hill Fields.

Some of Britain's grandest lidos are lost forever, such as the stupendous Super Swimming Stadium in Morecambe, which held Esther Williams-style swimming revues and weekly heats of the Miss Great Britain contest. Or Blackpool's Open Air Baths, a lavish beaux arts-style swimming temple the size of a football stadium, complete with a domed main pavilion and a pergola-shaded rooftop cafe. Or the colossal New Brighton Bathing Pool, which attracted more than a million swimmers in 1934. At the time, these were some of the largest pools in the world, but they were frequently structurally unsound and built on unsustainable visitor numbers, destined to become the dinosaurs of the lido world.

If you look beyond lidos, there are contemporary alternatives for outdoor communal swimming. The idea of a floating lido, for example, has been repeatedly explored. Such a facility existed on the Thames in the 19th century (although it was essentially just a closed-off portion of the river); artist Tracey Emin has expressed a desire to design one; and 10 years ago architect Alex Lifschutz proposed an Olympic-sized floating pool for the Coin Street estate, to be moored off the South Bank. With a glass-sided swimming tank, poolside restaurants, and a transparent roof that would collect solar energy to heat the pool water, it was a tantalising prospect, but the economics didn't pan out, Lifschutz explains. "It was too expensive, even if funded by the restaurants around it. We've now got a site on land [on Doon Street], and we've just put in a planning application for a swimming pool and sports centre of a more conventional size, but funded by a 40-odd storey tower. There's an understanding now of the huge economic burden of a swimming pool, and we need the housing to subsidise that."

While the funding of lidos and public pools has been the subject of heated debate in Britain, a floating pool, the Piscine Josephine Baker, opened in Paris just last week (and promptly closed again, after it was found that tiles were coming loose from its base). On the whole, though, things are rosier for public swimmers in France. Home of the famed Piscine Molitor, the pool that arguably started the lido craze, Paris has more Olympic-sized swimming pools than the whole of Britain put together.

In reality, the Piscine Josephine Baker is more of a swimming pool barge hugging the bank of the Seine, but it could prove to be a new solution for public bathing. "It has a sliding roof, and you can also open the facade towards the river, so when you're swimming in the pool you have the impression you're swimming in the Seine," says its architect, Robert de Busni. "And in a way you are, because it's the same water. The pool takes it from the river and treats it, then we give it back to the Seine more pure than when we took it out." The pool was a challenge to design and build, according to de Busni, since it combines conventional and naval architecture. In order to get it to its location in the 13th arrondissement, it had to be designed in pieces and assembled on site, with the result that it can be taken apart "like Lego" and rebuilt somewhere else, says de Busni. "We can put it anywhere. We can take it to London if you like."

Another promising new branch of pool design opened recently in Gloucestershire: a commercial eco pool. Domestic eco pools have been around for a few years, but this one is part of a luxury health "artspa" at the Lower Mill Estate - a sort of Hamptons-style second-home complex-cum-nature reserve near Cirencester. Rather than treating the water with chlorine and other chemicals, eco pools use reed beds to clean it naturally, and the water flows like a slow river, preventing the build-up of algae and debris. As a result, they're not only more environmentally sound than conventional pools, they're also friendly to wildlife. "I have this sort of ridiculous notion of Swallows and Amazons, and swimming in rivers and ponds as a kid, and it just appealed to me, the idea of having a swimming river," says Jeremy Paxton, Lower Mill Estate's developer. "It's a fabulous habitat - we get swallows and housemartins and dragonflies, we even had a kingfisher come by the other day." Paxton is already planning a whole village based around a much larger eco pool, which residents will be able to dive into from their balconies.

This exclusive fantasy world might be a long way from your average municipal pool, of course, but that's possibly the only context in which such ideas are ever likely to be realised. And once developed, there's no reason why eco pools couldn't work in the public realm. Paxton estimates his cost 25% less to build than a conventional domestic swimming pool. "I'm of a vintage where lidos existed and I loved them," he says. "It would be fabulous to see a proper public lido heated by solar and wind power, filled by rainwater run-off, full of wildlife. Could it work? Absolutely."

A public eco lido in every town might be some way off, but it's a persuasive idea, less primordial soup than garden of Eden. Perhaps such ideas run counter to the concerns of the lido conservationists, but there is room for alternatives; a return to our primal state, underpinned by the sustainable technology of the future, could be the next evolutionary step for aquatic apes everywhere.