Deborah Voigt, saucer-eyed with apology, sweeps late into her favourite restaurant, round the corner from the San Francisco Opera, to a chorus of "Hi Debbie" from everyone in sight. She is an all-American lady: cheerful and frank in demeanour; in appearance, trim of figure, averagely tall, carefully made-up, with blonde hair buoyant and well coiffed.

But in 2003 Voigt - one of the most revered dramatic sopranos of her generation - was sacked from a production of Richard Strauss's Ariadne auf Naxos at the Royal Opera for being too fat. Voigt let the fact slip the following year: asked by a British interviewer why she was never seen at Covent Garden, she decided to tell the truth. She had no idea that it would start a media furore, but it made news across Europe and the US. When the story broke, she was staying in a hotel in Geneva and had to change her name on the registration to get the phone to stop ringing (the first thing that came to mind was "Mrs George Harrison" - she's a huge Beatles fan).

Just over two years ago, the now 46-year-old Voigt was obese: the sort of extreme over-weight where her features had disappeared into a pillowy anonymity and she would panic when given a chair with arms. "I didn't feel good. My knees were starting to hurt," she says. "I knew it would be only a matter of time before diabetic or hypertensive problems. I was out of all the large-lady dress sizes; I was about a size 28 or 30 [UK size 30-32]. I think back and I just can't believe it."

Later in 2004, she was back in the news: she had had gastric bypass surgery, she announced - a radical intervention that limits stomach capacity. After two years, patients can lose 80% of excess weight. She is now a UK size 14-16, and just over 10 stone. At her heaviest, she was 25 stone.

And, lo and behold, she is not only due to sing a London recital at the Barbican next June, but she has also been invited back to the Royal Opera House to star in that production next year. When she got the call, she says, "I had to chuckle. Peter Katona [the Covent Garden head of casting who was responsible for the sacking] is going to have to take me out for a really good lunch."

Was she not tempted to tell them to go to hell? "You know, a handful of people made this decision, maybe two or three," she says. "For me to say I am not going to sing in that opera house based on a decision made by just a few people would be foolish. I am an international singer, I want to sing in England and that's your major opera house. So I am going back." She will also star in Tosca the following year.

The question everyone seems to want answered is: can she still sing? A voice does not exist in isolation but depends on the workings of the musculature of the stomach and abdomen. Change the fleshy support system of the instrument, and you could change the nature of the sound. After Maria Callas lost a great deal of weight, some thought that her voice lost a portion of its beauty (though the idea that fat people always make better opera singers is surely myth, since there have always been slender divas). Voigt herself says, "I don't think my voice has changed, but I am only hearing it from inside, so I can only speak about the sensation of singing. Every 20lbs I lost, I felt less rounded and less able to support the sound; well, that was because my support system" - she gestures at empty space around her now slim hips - "was vanishing. At 150lbs heavier, you take a breath and those muscles are already engaged, you don't have to think about it. Now, I have to think about it, about how things line up." She pauses. "In terms of the timbre, the size? I don't think the size of my voice has changed. Maybe it's a little brighter, more silvery rather than gold."

Voigt is still baffled about the fuss. "I never dreamed that telling the truth would become the story that it did," she says. She seems far too straightforward to have outed the Royal Opera House deliberately to attract controversy. She laughs when she tells me that one of her former publicists said she was too bland, too pleasant, and needed a bit of scandal to raise her profile. The idea of doing that turned her - a regular midwestern girl from a churchy background - cold. "Well, he was right in a way," she says.

In fact, the fascination of what Voigt calls "the Covent Garden debacle" is surely obvious. Leaving aside our generalised cultural anxiety about obesity, into which l'affaire Voigt feeds directly, there are the multiple idiosyncrasies of opera. It has, fairly or otherwise, become known for its fat ladies singing. In an artform that traditionally valued the quality of a voice over all things, it long seemed reasonable to cast fleshy divas, sometimes advanced in years, to play sex goddesses or consumptive teenagers. Looks were secondary. Audiences were used to suspending disbelief.

But, though individual opera houses operate differently, it is more and more rare to see women cast entirely against type. Some argue that it is about time the opera world accepted that singers have to be right for a part dramatically and physically - audiences are used to realism in the movies. Some still contend that in opera the voice must come first. Others, including Voigt, point out the sexism inherent in all this. "I once read a review pointing out how overweight I was," she says, "but they said that the tenor had shoulders like a linebacker. They did not also say that he had a stomach like a nine-months-pregnant woman."

She has resigned herself to the fact that people will assume she had the surgery because of the Covent Garden sacking. But, she says, "I started thinking about it a long time ago - I've been dealing with this problem my entire life. I had my consultation prior to the Covent Garden debacle and the surgery after. It is not a procedure one undergoes simply because a few people say your hips are too big. It's too dangerous." She says she tried everything to get weight off - every kind of diet, exercise regimes - for years, but to no long-term avail.

"Anyway, I was looking for a time when it would be possible to have the surgery and, lo and behold, I had all this time off [in summer 2004] because Covent Garden had fired me. And they had had to honour their financial commitment. So, if you want to get technical and ironic about it, Covent Garden paid for the operation." If you want to get even more ironic about it, the British taxpayer helped out: about a third of the Royal Opera House's income is from the public purse.

The three-and-a-half hour operation involves dividing the stomach with staples to create a new, smaller pouch. The small intestine is also divided into two segments, one of which is connected to the new pouch so it can empty food contents into the bowel. The lower stomach and a portion of the small intestine is thus "bypassed". It was done at Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan, which specialises in bariatric (obesity) surgery.

"Sadly, I am still a foodie," she says, picking at her chicken-and-noodle salad. "It has taken away the pleasure in eating, to a certain extent. Not in terms of taste, but in the fact that I can't eat that much.

"I was out to dinner a couple of nights ago in a little diner, and I looked over and there was a man eating a big greasy hamburger and french fries and he was just . . . well, not being piggish about it, but really enjoying it. You know, I really miss that." She still has the occasional McDonald's. "But I have a Filet-o-Fish and I take the bun off the top, and I only eat half of it. About six months after the surgery I had this craving - I've got to have some McDonald's. So I went to a drive-through. And I forgot that after the surgery you have to eat differently: you have to eat slowly, you have to chew, take your time. And driving along, I took a handful of fries and put them in my mouth ... 20 minutes later I was so ill, I had to pull in off the road. It was so ingrained."

She was addicted to food, she says. "I used food the way that alcoholics use alcohol and drug addicts use drugs. If I was sad I ate, if I was happy I ate, if I was lonely I ate. And I grew up sitting on a piano stool and singing and not running around playing soccer. My fingers were in great shape."

Even with the reduced stomach capacity, "I could really sabotage myself if I wanted. I could eat a Snickers bar every 15 minutes and put on weight ... I still have the same compulsions and addictions to food that I had before. You are told [about the operation]: this is not a cure, it's a tool. It's a way of getting off a lot of weight, seeing results, feeling them and hopefully learning some better behavioural skills along the way."

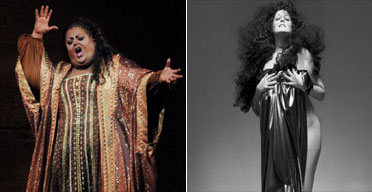

That involves working out most mornings: at the moment, she has a particular incentive. After her current stint singing Amelia in Verdi's Un Ballo in Maschera (A Masked Ball) in San Francisco till the end of this week, she is off to Chicago (with her dog Steinway, her constant companion), to take on Strauss's Salome, a part that notoriously involves the dance of the seven veils. A newsletter from the Lyric Opera of Chicago recently featured an astonishing publicity photograph of Voigt standing on a plinth, naked but for a length of fabric and spectacularly bewigged. "It's a combination of excellent lighting and a contortion of body," she says of the picture. "It involved sticking my hip out so far, I practically needed chiropractic afterwards."

Will she get naked for the part? "You know, I had an email from the costume designer a few weeks ago saying, 'Will you take your top off? Will you show your backside?' I said, 'I don't know, and probably won't until very late in the day.' I don't want to be pressured into anything that doesn't seem appropriate. My poor parents! They were a little taken aback when they saw the photo. They are very conservative, very churchgoing people."

Salome is a role, she says, that she would never have been asked to do before the surgery - despite the fact that she is acknowledged as one of the great Strauss interpreters. "I'm not sure I would have have wanted to see me, 150lbs heavier, singing Salome. I think opera houses have to compete for entertainment dollars just like anyone else ... I would like to believe that the most important thing in opera is the voice. But at the same time it's a business, just like anything else."

Unsurprisingly, Voigt's views on all this are ambiguous. "It always bothered me when people said such and such is not believable in a part because we don't believe that [at her size] the tenor would love her. As a woman who's always had a boyfriend or a husband or a lover, it's just not true. There are always people out there who will love you, whatever your size." (Voigt is, she says, in the middle of a break-up with her boyfriend and, what is more, she is pretty thrilled that Paul McCartney is newly available - "He should be seeing an international opera star!")

On the other hand, she has accepted that the pragmatic decision to lose weight means she will have more career options - she will be asked to take on those Salomes, those Toscas and Strauss's Eygptian Helen, "who is supposed to be the most beautiful woman in the world". She is also enjoying actually being able to act. "I've just been doing Sieglinde [in Wagner's opera Die Walküre] in Japan. I've done that production many times, and this was the first time since losing weight. Moving around was so much easier; the way you can use your body to express a character is really something. Things don't read the way they do [on a larger figure] as they do on a small frame. That's just the fact of matter."

She also hated being judged for her size. "I had a boyfriend who was not terribly discreet, and he would tell me about the sniggers in the audience when I walked on stage. Of course I knew these things, and I was never OK about it in the way that some of my heavy-singer colleagues are OK about it - or seemingly so. I knew I could sing circles around these people, but I also knew that Debbie Voigt was not supposed to be 350lbs."

Paradoxically, she still thinks of herself as obese. "Last night, in rehearsal, I went to sit down in the wings and they brought over a flimsy-looking folding chair. I couldn't even speak. Or walking along the street with a friend the other day, I noticed our shadows were the same size - I was, like, 'Oh my God, look!'

"I hesitate to talk about it because I'm sure it sounds flipping insane. But in the old days, I'd be sitting in [an airline seat in] economy and constantly leaning away to avoid disturbing my neighbour. Now I sit down, cross my legs and there's room either side of me".