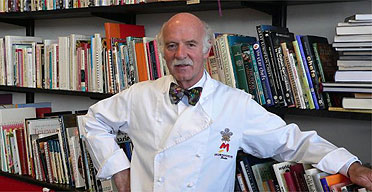

Cookbooks in my house end up with pages turned down and spattered with food so I'm surprised that the Swiss master chef Anton Mosimann even lets me near the famous collection he has built up over a lifetime of global culinary adventures.

Housed in his chefs' academy in a quiet south-west London backstreet, the library is a modern space, lit by huge windows and with a ceiling high enough that you could imagine clouds forming. Nearly 6,000 cookbooks stretch along the shelves, taking in seven languages, half a dozen centuries and a staggering diversity of subjects. Some of the ingredients in Mosimann's older books are fairly unappealing. Boiled cow's udders jump out from Meg Dodd's 17th-century book, Cookery: A Practical System of Modern Domestic Cookery, sliced and served with tomato or onion sauce, unless you would prefer them simmered and salted, served cold with oil and vinegar.

Many of the earliest recorded recipes seem benign by comparison, such as the 1,800BC Sumerian clay tablet bearing an ale found to be excellent by modern brewers. And the Greek commentator Athenaeus's treatise The Deipnosophistai (The Learned Banquet) in the second century BC features dishes as familiar as stuffed vine leaves and cheesecake.

Athenaeus mentions more than 20 other cookery writers who preceded him, all lost, alas. One famous work survives from antiquity, however - De Re Coquina (On Cooking), a chronicle of the culinary obsessions of a first-century Roman, Marcus Apicius. His search for ever more outre delicacies included snacking on nightingale tongues and feeding pigs with dried figs before killing them with overdoses of honeyed wine.

Among the earliest handwritten recipe collections in English was The Forme of Cury (cury meaning cooked food, derived from the French cuire - to cook), compiled around 1390 by a master cook to Richard II to show readers how "to make common pottages and common meats for the household, as they should be made, craftily and wholesomely". A decade earlier, Guillaume Tirel, chef to the French royal family, produced the first known French cookbook, Viandier. Original copies no longer exist, although an 18th-century version of The Forme of Cury is available on Amazon and you also can download it free from manybooks.net.

England's entry into the printed cookbook stakes occurred in 1500, when Richard Pynson - one of the first English printers - published The Boke of Cokery [sic], though it was thought to be lost until a copy reappeared in 2002 during a clearout by the Marquess of Bath at Longleat House.

François Pierre de la Varenne produced the first culinary bestseller in 1651. Le Cuisinier François replaced medieval anarchy and Renaissance fantasy with a reliance on good stocks and a harmonious fusion of ingredients - an approach that clearly chimed with cooks, who snapped up 250,000 copies. Translated into English in 1653, Varenne's success doubtless inspired Robert May to produce the first comprehensive English language cookbook, The Accomplisht Cook, which included tips such as "how to boil a pike in city fashion" and "à la mode ways of dressing the head of any beast". This year a copy discovered in a trunk fetched £4,500 at auction.

With so many wonderful historic books in his library, which would Mosimann grab should an overzealous student's flambé in the academy kitchen set the library ablaze? He plumps for a work by Bartolomeo Scappi, a 16th-century chef to the Pope, and takes down a 1605 edition (a 1570 first edition sits alongside other rarities in his safe) to marvel at the beautiful illustrations. "It's amazing how little has changed," he says. "Ladles, pots, fish kettles, just like you see today."

Some of the most intriguing recipes come from the 17th- and 18th-century books produced by the first wave of women cookery writers, of which perhaps the best known is Hannah Glasse's The Art of Cookery (1747). Trained to run domestic kitchens and informed by a need for practicality rather than fancy, the recipes are a tantalising mix of the familiar and startling.

Mace and nutmeg appear frequently, as do barberries - a sharp-tasting fruit still used in Middle Eastern dishes under the name zereshk. Pickling is common, along with tips on rescuing meat of dubious freshness or guidance on skinning swans. Pike and lamprey, meanwhile, are common fish dishes - indeed, Henry I was reported to have died after eating "a surfeit of lampreys". Yet at times, the leap from aged to modern menus doesn't seem quite so big. Leafing through Elizabeth Raffald's 1769 book, The Experienced English Housekeeper, a dish like "Ragoo of Pig's Ears" might not look out of place today on the menu at St John, Fergus Henderson's acclaimed Smithfield temple to "nose-to-tail eating" in London.

So if the proof of the pudding is in the eating, why not try this recipe from Eliza Smith's The Compleat Housewife (1742). Historic recipes are often lax with quantities and cooking times, so educated guesses are in order for some of the following.

Marjoram pudding

Large tub plain cottage cheese (in place of "the curd of a quart of milk")

Marjoram

3 eggs

Few drops rosewater

Nutmeg

Sugar

3/4 lb butter

½ pint of double cream

Chop marjoram "as fine as dust", then beat together all the ingredients, adding the melted butter last. Line a baking dish with a thin sheet of pastry and pour in mixture. Top the tart with a criss-cross of pastry, dab with melted butter and bake in the oven until cooked.