I was a bit off colour. More languid than I normally am first thing in the morning. My head felt denser than usual, as if it had been filled overnight with sand. But it was my turn to make the tea, so I rolled over and ... pffff. One ear gone.Then, as I sat up, I kept on going past the point of perpendicularity, like a Weeble. The room swam. The Ps and Fs in my ear grew louder. I felt sick.

Sudden neurosensory hearing loss (SNHL) is called that because they can't think of anything better to call it. This is because they don't really know what it is. What is known is its effect: hearing is taken away suddenly and the victim loses all sense of balance. Any movement results in acute vertigo and vomiting. You can lose vision, too. The most likely causes are either viral or vascular, resulting in the denial of blood to important bits of neural kit. Permanent damage is inflicted on the tiny hair cells or cilia in the inner ear, which are vital conductors of auditory information to the brain. Once torched, they don't grow back. SNHL is really quite calamitous.

An hour after the first attack, when my wife and two children carried me deaf, blind, immobile, nauseous and incoherent into the doctor's surgery, my GP's first thought was that I had a brain tumour. In hospital an MRI scan revealed nothing. "Sit tight," they said.

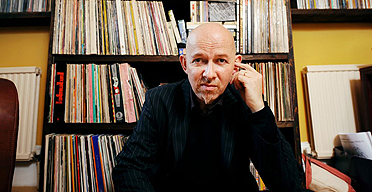

"But my hearing is my favourite sense. I need ears for work. Music is my great passion in life: I write about it and I do it a bit too. I'd rather lose an eye, a foot ..."

"We don't guarantee that hearing will return," the surgeon replied. "But don't worry. It may." He then sidestepped his own sidestep. "Anyway, lots of people live perfectly normal lives with only one ear."

I emerged from hospital a week later, profoundly deaf in one ear, my brain refusing to let my ear go quietly. Its reaction is to fill my head with noise. Imagine the sound of pressurised air escaping from a central heating valve. That's the sound that fills the right hemisphere of my head round the clock. Concealed within that hissy cloud there's another layer of far subtler sounds. In the dead of night, when my wife is breathing silently and there is no other sound going in my good ear, I can hear beneath the pfffff a strange polyphony of whistles and cries, like a drowning choir, accompanied by a tiny monkey playing a teeny pipe organ. It can be quite soothing. But if my wife suddenly exhales through her nose, or rustles the duvet by moving her head slightly, then all hell breaks loose. I hear gasping cats and boiling kettles. When two or more voices are joined together in amiable conversation, I hear trains entering underground stations. Right now, sitting at my computer in an otherwise silent house, the minuscule hum of the machine is at a pitch somewhere between the central-heating pffff and the cat's gasp.

This is not conventional tinnitus, but entirely reactive to input in the good ear. It is the auditory equivalent of the illusion experienced by amputees - the feeling that the missing limb is still attached. My brain is generating sound to compensate for the lack of auditory activity in my ear.

So where does that leave music? It leaves music pretty much nowhere. Put it this way: I can hear music but I can't listen to it, not for pleasure. What I can hear is monophonic, on the far side of whatever uproar happens to be filling my head. Music is merely a sound. It is not, for me, the same thing that it was for a good 40 of my 47 years, right up until the end of August.

I don't know how you hear music. I imagine that if you like music at all then it has, in your head, some kind of third dimension to it, a dimension suggesting space as well as surface, depth of field as well as texture.

Speaking for myself, I used to hear "buildings"... three-dimensional forms of architectural substance and tension. I did not "see" these buildings in the classic synaesthetic way so much as sense them. These forms had "floors", "walls", "roofs", "windows", "cellars". They expressed volume. Music to me has always been a handsome three-dimensional container, a vessel, as real in its way as a Scout hut or a cathedral or a ship, with an inside and an outside and subdivided internal spaces.

I'm absolutely certain that this "architecture" had everything to do with why music has always exerted such a hold over me. I think music was the structure in which I learned to contain and then examine emotion.

I've always kept quiet about this architecture business, partly because it sounds pretentious and even slightly self-congratulatory (you hear Amy Winehouse, I hear Apsley House), but also because I'd never been entirely confident that "architecture" was what I really meant. Maybe "hearing music architecturally" was just me being inarticulate.

But I am confident now. "Architecturally" was precisely right. What I hear now when I listen to music is a flat, two-dimensional representation. Where I used to get buildings, I now only get architectural drawings. I can interpret what the drawings show, but I don't get the actual structure: I can't enter music and I can't perceive its inner spaces. I've never got much of an emotional hit from technical drawings. Here is what really hurts: I no longer respond to music emotionally.

The celebrated neurologist and author Oliver Sacks has recently published a book, Musicophilia, all about the relationship between the brain and music. In it he tells the story of a Dr Jorgensen who lost all hearing in one ear following an operation on a nerve. He, like me, afterwards found music as flat and unengaging as a line drawing. Dr Jorgensen did not get the tinnitus, however. He enjoyed blissful silence in his duff ear. Yet music for him remained steadfastly flat.

Jorgensen wrote to Sacks to tell his story and to pass on the interesting information that, counter to all logic, after about six months' dogged listening, he fancied that his single ear was beginning to offer him a "pseudostereo effect", giving him "ample compensation" for the loss of real stereo. He speculated on the possibility of his brain doing a bit of surreptitious rewiring: "Hearing fibres might have crossed in the corpus callosum to receive input from my functioning left ear ..."

Sacks is doubtful about the extent of such rewiring, but goes on to ruminate on what might be expected of a brain in such circumstances, not least with regard to the brain's capacity to register "space" in music as an active element in its emotional reach. He talks about the "recruitment" of different brain areas not normally used for the purpose.

I began to do little experiments on myself. I dared not listen to my favourite music for fear of what I might hear (imagine: Miles Davis as a papery squiggle), but I kept up a steady drip of new and potentially interesting (quiet) music into my one good ear, on the off chance that something desirable might happen. And on November 11 I tottered downstairs to watch the Remembrance Day broadcast at the Cenotaph.

I am always affected by the Cenotaph ritual, in particular the Guards' stacked Nimrod, followed by When I Am Laid in Earth (from Purcell's Dido and Aeneas) and Beethoven's Funeral March: grey greatcoats, deep trombones, utter stillness. Gets me every single time. Every year I watch and wait for Nimrod's unfailing impact on my metabolism, fascinated by the serpentine passage of emotion through my body, from its bed in the pit of my stomach, slow as a Guardsman's dead march. It's an extraordinary sensation, made all the more so because of its complete and utter predictability.

So I switched on and sat there. What if nothing happened? I needn't have worried. David Dimbleby had only to intone, "And now, from Elgar's Enigma Variations ..." and, before a single Guardsman had so much as licked his mouthpiece, I was a mess.

Yes, of course, I was snivelling for my lost cilia. But also, quite clearly, my psyche was not going to run the risk of me being unable to feel a thing in the face of stick-on emotional music. But that wasn't the interesting thing. What was really interesting was that, as I sat there shuddering and trickling, I began to hear the music better. Melody, metre, a little bit of timbre, the puffiest cloud of harmony. Yes, yes ... I began to sense the tiniest swelling of architectural form in my head. You wouldn't have called it the Taj Mahal, but equally, this was no papery squiggle.

When it was over, I stuck the Purcell on my stereo. I thought: if I'm getting that much from the TV, what am I going to get from a good recording coming out of big speakers? I only got discomfort and bewilderment. The music was close to unreadable. It was certainly unbearable. I turned it off and let the uproar in my head subside.

Oliver Sacks was in London a week or two later, talking about his book. He kindly agreed to meet. We sat in the foyer of his hotel and he listened, kindly and attentively, taking notes. He seemed interested by the Cenotaph experience and my uncooked theory of music-as-emotional-petri-dish. He then told me that he'd recently lost the sight in one eye and that it had broken his heart.

Sacks has maintained a lifelong fascination with, and experimental expertise in, the subject of stereoscopy. He has tinkered with the science and the showmanship of seeing with two eyes since the 30s and has developed an almost metaphysical affection for the way stereoscopy makes the world lovable, as well as livable in. He pointed a thumb out of the window of the breakfast bar and drew my attention to the thick, shifting foliage on the other side of the glass. "Beforehand," he said, "I would take active pleasure in the movements of tricky jungle surfaces, and the way we perceive depth and distinctiveness in the most complex visual environments. But now," he hesitated, obviously not wanting to labour the point, "everything's rather flat."

The Monophone and the Monoscope felt each other's pain and agreed to correspond.

A few days later I tottered off to watch a preview of the Led Zeppelin concert film The Song Remains the Same, which was coming out on DVD with remastered sound. It's a daft film but I am fond of it, and it seemed an ideal opportunity to test a couple of things: the significance of familiarity in any emotional response to music, and whether there was anything in the vague feeling carried over from the Cenotaph that seeing the music helped with the process of hearing it. (I know what you're thinking: Led Zeppelin? Emotion? What kind of weirdo are you? But the fact is, I have always got a lot of emotional pleasure from Led Zeppelin, a pleasure that is, I suspect, not unakin to Sacks's pleasure in the shifting of jungle foliage.)

Crash bang wallop. I lasted three songs and had to leave the cinema clutching my head in a state of disorientation. The reactive tinnitus took me close to the threshold of actual physical pain. Great swaths of the music were simply unreadable. Jimmy Page's guitar, in particular, was a storm of detuned noise.

I sent an email to Daniel J Levitin, musician, neuroscientist and the author of This Is Your Brain on Music, to see what he thought. I explained about the flatness, the absence of warmth and timbre. This is what he said: "We don't know much about those higher-order qualities. I know about them as a recording engineer and producer, but not as a scientist. I suspect that something has gone awry in the inner ear and so the cortex isn't getting all the information it's accustomed to. In the case of pitch, the brain can fill in the missing information, but with those higher-order properties not."

So there it is. I can make analytical "sense" of music most of the time because my brain can compensate for any loss of pitch, which is the very first quality that differentiates music from pneumatic drills and bickering children. What my brain can't seem to do is fill in the timbre, warmth, texture and depth - what Levitin calls the higher-order qualities.

Does this mean that it is the higher-order qualities that generate the emotional response to music? Or is it just me? Does it merely mean that in order for me to be able to register music's architectural dimension - and therefore have a special place in which to register emotion - I need warmth, timbre, texture and depth? This might explain why, if I listen hard to music in my new condition, I feel perfectly capable of making aesthetic judgments, even as I feel nothing much at all at the emotional level.

A week or two later I had a kindly letter from Oliver Sacks, enclosing a copy of a piece he wrote for the New Yorker, Stereo Sue, about a woman who had "acquired stereoscopy after almost half a century of being stereo-blind". It was, she said, "a constant source of delight". The neurological basis of Sue's transformation was by no means clear, but the impact of it was abundantly so.

Stereo Sue described to Sacks the effect of being "inside" a snowfall for the first time, because she was able now to see it shifting and flowing around her in three dimensions, as opposed to "looking in on it", as she had done all her life. "I watched the snow fall for several minutes, and, as I watched, I was overcome with a deep sense of joy." She might have been describing how I used to feel when I listened to John Coltrane or Marvin Gaye or the St Matthew Passion or, for that matter, Led Zeppelin. I used to inhabit all of them, as they inhabited me, in three-dimensional space. Now I only look in.

Sacks was particularly engaged by my Cenotaph episode. "What you say about the power of emotion to restore a sense of depth and spaciousness (to music) is extremely interesting," he wrote. "You must have (and will always have) the memory of such spaciousness, and the power to evoke it in imagination - and 'imagination' imagery is neurologically almost equivalent to perception. One might expect that such a power, while not available (or less available) voluntarily, could occur spontaneously by association with emotion, a memory. But you have to sort this out for yourself." He is currently reading a book entitled A Singular View: The Art of Seeing With One Eye.

So I know that the only way forward with this is to keep listening to music, even though it hurts. The more I listen, the greater the chance of cortical adaptation, but also the greater the chance my memory has of helping me to rediscover the sensation of what music used to do.

After six months, a fair amount of adaptation has already taken place. I decided to do away with my walking stick a couple of weeks ago and I now swank around slowly, like a cowboy without his horse, legs spread. And I have begun to force myself to share space with other people while they talk. It isn't easy, but it's easier. It feels like progress.

But music is still perceived flatly in a sliver of space on the far side of the noise in my head. It kind of hurts. I do find, though, that I am learning to "read" music in a different way. It involves a lot of effort.

Music has always penetrated me effortlessly - that has been part of my pleasure in it. Its power to get inside, to saturate, has been its greatest power. And in response I have always been delighted to be the passive recipient. But that doesn't work any more. I now have to fight to hear music: to resist the discomfort that arises from listening and to clear the space in my head for music to have some wriggle room - and of course, or so I fervently hope, for music one day to snap into three dimensions and give me my buildings back.