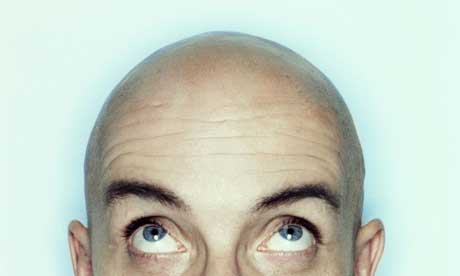

When it comes to wrapping up on a cold winter's day, a cosy hat is obligatory. After all, most of our body heat is lost through our heads – or so we are led to believe.

Closer inspection of heat loss in the hatless, however, reveals the claim to be nonsense, say scientists who have dispelled this and five other modern myths.

They traced the origins of the hat-wearing advice back to a US army survival manual from 1970 which strongly recommended covering the head when it is cold, since "40 to 45 percent of body heat" is lost from the head.

Rachel Vreeman and Aaron Carroll, at the centre for health policy at Indiana University in Indianapolis, rubbish the claim in the British Medical Journal this week. If this were true, they say, humans would be just as cold if they went without a hat as if they went without trousers. "Patently, this is just not the case," they write.

The myth is thought to have arisen through a flawed interpretation of a vaguely scientific experiment by the US military in the 1950s. In those studies, volunteers were dressed in Arctic survival suits and exposed to bitterly cold conditions. Because it was the only part of their bodies left uncovered, most of their heat was lost through their heads.

The face, head and chest are more sensitive to changes in temperature than the rest of the body, making it feel as if covering them up does more to prevent heat loss. In fact, covering one part of the body has as much effect as covering any other. If the experiment had been performed with people wearing only swimming trunks, they would have lost no more than 10% of their body heat through their heads, the scientists add.

The researchers then decided to look at several other widely held beliefs to see if there was any published scientific evidence to support them. In many cases, they found several studies that completely undermined them. "Examining common medical myths reminds us to be aware of when evidence supports our advice, and when we operate based on unexamined beliefs," they write.

Another myth exposed by the study was that sugar makes children hyperactive. At least a dozen high-quality studies have investigated the possibility of a link between children's behaviour and sugar intake, but none has found any difference between children who consumed a lot and those who did not. The belief appears mostly to be a figment of parents' imaginations. "When parents think their children have been given a drink containing sugar, even if it is really sugar-free, they rate their children's behaviour as more hyperactive," the researchers write.

The warning that snacking at night makes you fat is on similarly thin ice, Vreeman and Carroll discovered. At first glance, some research suggests there may be a link, with one study showing that obese women tended to eat later in the day than slimmer women. But according to the BMJ article, "The obese women were not just night eaters, they were also eating more meals, and taking in more calories makes you gain weight regardless of when calories are consumed."

The researchers also have some unwelcome news for those hoping to survive the festive excesses by turning to hangover cures. After an extensive review of evidence for the curative benefits of bananas, aspirin, vegemite, fructose, glucose, artichoke, prickly pear and the drugs tropisetron and tolfenamic acid, they conclude that none has been proven to cure hangovers. "No scientific evidence ... supports any cure or effective prevention for alcohol hangovers," they state. "The most effective way to avoid a hangover is to consume alcohol only in moderation or not at all."

The team went on to show that contrary to popular belief, the Christmas plant poinsettia with it blood-red leaves is not toxic, and that suicides do not rise over the holiday period