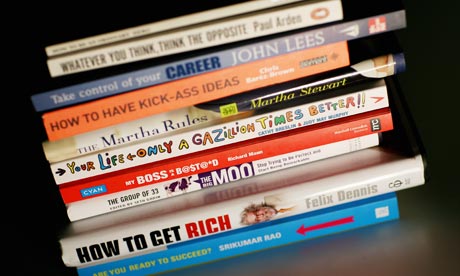

Recently, I made the mistake of looking over the non-fiction charts. It was a depressing experience. In Nielsen, books by Diana Athill and Barack Obama are just about the only islands of sanity in an ocean of celebrity biographies, celebrity cookbooks, celebrity TV spin-offs and – most egregious of all – self-help books. Books like Feel the Fear and Do It Anyway and The Element are dominant, on Amazon, Paul McKenna has taken up both positions four and six in Nielsen's paperback charts with I Can Make You Sleep (surely his truest ever claim!) and I Can Make You Thin, while Rhonda Byrne sits at number three amongs the hardbacks with The Secret.

It was the continuing presence of The Secret that most inclined me to despair. It's bad enough that all these self-help books should have outstayed their annual welcome and continued to dominate the charts weeks after the January self-improvement surge. That one of them is more than two years old – and more than usually awful – and still riding so high is especially annoying.

For those lucky enough to have avoided The Secret so far, some explanation is in order. The book rests on the theory that the "ancients" held a secret that can generate wealth and happiness. This "secret" was shared by (in chronological order) Plato, Da Vinci, Shakespeare, Newton, Beethoven, Einstein and Byrne herself, hitherto an Australian daytime TV producer. It pertains to "The Law Of Attraction" and the fact that positive thinking can change real life events. Just thinking about things you want intently enough will make them happen. Which is odd, because in two years of intense wishful thinking, I still haven't managed to make The Secret disappear.

The fact that it's transparent hocus pocus isn't the only thing that annoys me about The Secret. This co-opting of the "ancients" is one of the most notable trends in current self-help literature. Every guru from Alain de Botton to the Dalai Lama has recently started co-opting too-dead-to-sue thinkers into their own philosophies. De Botton recently gave a succinct summary of the idea that the "ancients" were into self-help here. It is ridiculous. Now, I'm aware that to most readers of these pages I'm pointing out the blindingly obvious. To say that "De Botton is talking nonsense" is, after all, just about the best example of a tautology that I can think of. Even so, these ideas have caught hold so firmly recently that it's still worth attempting to debunk them.

When most "ancients" particularly of the Greek variety spoke about the "good life", they were not really referring to the work-play balance. Plato, Socrates, Aristotle and their bearded kin were grappling with questions of eternity, not trying to come up with the best system for keeping your in-tray empty, impressing your boss and getting rich. Achieving "eudaimonia" was not necessarily about pampering yourself. Indeed, if you genuinely were to follow these "ancient" teachings, chances are you'd end up feeling a whole lot worse. Even Epicurus – to give the most frequently misrepresented example – recommended a life of frugal asceticism, and would be horrified at the indulgence of the self-helpers.

The reality is that, like global warming and oil wars, self-help is entirely the product of modern capitalism. Its roots can only really be traced as far back as 1859 when Samuel Smiles decided that anyone could get along in newly industrialised Britain so long as they were thrifty and hard-working - and published the daddy of all self-help books called (unsurprisingly) Self-Help.

The idea that those struggling in the squalor of Victorian poverty had it in their power to do anything about their miserable lot was ludicrous. The book was neatly summed up by Robert Tressel in the Ragged Trousered Philanthropist when he said it was "suitable for perusal by persons suffering from almost complete obliteration of the mental faculties". But the fact that Self Help was crap was immaterial. What really caught the world's imagination was the fact that it sold more than 250,000 copies. A trickle of books began to follow, which turned into a stream when Dale Carnegie's How to Win Friends and Influence People hit pay dirt in 1936. After that: a deluge. Research firm Marketdata estimated the "self-improvement" market in the US was worth more than $9bn in 2006. Over here, if you type "self-help" into Amazon.co.uk's search engine, just under 70,000 book titles appear (more than 180,000 with its American .com cousin).

Such statistics are overwhelming, but the most telling piece of data about self-help comes courtesy of an industry insider turned debunker Steve Salerno. He says that market researchers for the multi-million selling self-help publisher he once worked for discovered that "the most likely customer for a book on any given topic was someone who had bought a similar tome within the past 18 months."

That doesn't suggest to me that the books are working. There might be a lot of people out there who like to change their already successful lives every year-and-a-half, but the more likely and far sadder truth is that the same unhappy people are being repeatedly failed by all those books that promise them impossible hope. And now that the bankers have made suckers of us all, we can expect the shelf-help brigade to dominate the charts for a while to come. Those who object to the helpless being given false hope and the distortion of ancient ideas will have to endure a lot more cant from these people for the next few years. I guess we'll just have to be stoical ...