In 2003, I was intent on avoiding mirrors. They were the enemy. They reflected back wasted limbs, yellow skin, teeth like tombstones in a scared, skull-like face. I was in the process of starving myself to death, and whatever had made me do it, as I skulked past the looking glass I knew it wasn't a yearning to be attractive.

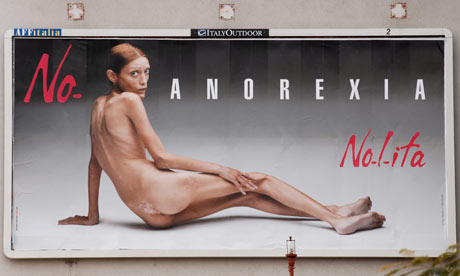

I'm not the only woman who has tried to make herself disappear. Anorexia nervosa, the disorder of pathological self-starvation, is on the rise, with an 80% increase in hospital admissions among teenage girls over the last decade. Pressure groups and parents complain that there is still a chronic shortage of specialist care, with many GPs apparently reluctant to refer patients for treatment in the early stages of the disease. And this approach leaves children and their families to struggle on alone - usually until it is too late for simple intervention.

I was hospitalised with severe anorexia five years ago, when I was 17, and only now can I truly begin to understand the cruelties of my condition. Anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any mental illness, but it remains one of the least understood. It is estimated that between 8% and 20% of sufferers will die as a result of the condition - half of them by suicide - and that a further 30% will remain ill for life, with complications including osteoporosis, digestive diseases, chronic anxiety, psychosis and heart failure. One or two in every 100 young women and one in every 1,000 young men has the disease, although anorexia has been recorded in every age group.

Anorexia has long been trivialised as a by-product of celebrity and fashion culture, and this media focus has sharpened since the death of two models in 2006. But the condition is actually far more than that: anorexia has been recorded since the 12th century as a psychotic strategy of self-control, which suggests that we have to look far beyond the pages of today's women's magazines for answers.

What anorexia often appears to offer is salvation from desire. My generation has grown up schooled like no other in the fine art of dissatisfaction - with our lives, our possessions and our bodies. For modern teenage girls the encouragement to do better, look better and have more can become almost unbearable. I have a visceral memory of lying on my bedroom floor after a particularly punishing exercise session, pounding the wall and sobbing "I don't need anything! I don't want anything! I mustn't want anything!" I was desperate to destroy the aching need I felt, not just for an extra biscuit or square of chocolate, but for life and all of its adventure. This had nothing to do with wanting to look prettier, and everything to do with a process of shutting the doors on life one by one.

Like 30% of sufferers, Hannah, now 23, developed anorexia after experiencing sexual abuse as a child. "I wanted to look disgusting and ugly," she says. "I wanted my heart to sputter and stop and my bones to thin, my organs to give up on me. Beyond everything, I think I just wanted the physical symptoms to kill me, so that I wouldn't have to make the final decision. If I had a heart attack caused by starvation, maybe that wouldn't really count as suicide."

Anorexia is a fight between brain and body, between what a teenager envisages as the rational, perfectible mind and a body that just won't do what it's told. We live in a world where young women are commanded to always look available, but never actually be so. If women's bodies are there to be consumed, our most drastic retaliation is to consume ourselves.

The action group Beat believes that too few GPs take anorexia seriously, particularly in its early stages. Sam, now in her 20s, tried to seek help when she felt her disease spiralling out of control. "I went to my GP quite early on and told her that I couldn't eat because I was scared of gaining weight, but she just told me to eat more nuts and gave me some vegetarian recipes. My overriding memory of that time was of being trapped in an endless black nightmare, with no visible way out."

Anorexia nervosa is the most lethal of all mental illnesses precisely because its physical and psychological effects are so profoundly entangled. It has been conclusively proved that prolonged starvation can actually provoke many of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa, causing sufferers to obsess over food and become depressed, self-destructive and suicidal. In 1944, for instance, researchers at the University of Minnesota enlisted and systematically starved 36 conscientious objectors - all healthy adult men with no psychiatric problems. Over the course of a year, the men lost 25% of their body weight, and were then fed normally again - with staggering results. All of the participants quickly began to display unusual psychological symptoms. They became highly distressed, agitated and bewildered, and developed bizarre rituals around eating, collecting recipes and hoarding food obsessively - not just during the experiment but, in some cases, for the rest of their lives.

One of the participants, Harold, told researchers in 2006 that the experiment was highly distressing "not only because of the physical discomfort, but because ... food became the one central and only thing really in one's life. I mean, if you went to a movie, you weren't particularly interested in the love scenes, but you noticed every time they ate and what they ate." The men became extremely disturbed by the idea of weight gain, and their reactions included pathological self-harm. One participant amputated three of his own fingers with an axe.

In recent years, the Minnesota study has been invaluable to psychiatrists wishing to understand the psychology and physiology of anorexia nervosa. But despite a growing recognition that successful treatment must involve provision for both the disordered emotions and the damaged physiology of the anorexic teenager, the availability of such care is extremely limited. There are currently more than 100 potential patients for every place in the UK's specialist treatment centres, most of which are in private hospitals. This lack of effective provision is another reason why GPs are reluctant to make referrals, often delaying until the anorexic displays potentially fatal weight loss.

It took me nine months of in-patient treatment to piece together the fragments of my body and sanity, and a further three years to make a full recovery. I am very lucky to have received such excellent care. Nearly half of the UK's specialist care teams for anorexia are in the south of England, with none at all in Wales and Northern Ireland. As such, patients are at the mercy of their postcode, and hospital admission on overstretched general wards is too often a matter of force-feeding followed by rapid discharge. While this physical rehabilitation may put the patient temporarily out of danger, it is useless without addressing her mental distress - and so hospital admission becomes a revolving door, with patients quickly starving themselves again on release. This pushes up the hospitalisation figures even further. Of the nine teenagers on my ward in 2004, only myself and a skeletal boy of 13 were on our first admission.

The high relapse rate points to a tragic waste of medical resources. If proper care were provided for more of Britain's anorexic teenagers, the disease could be treated effectively when it first presents. This is a baffling omission on the part of the NHS, which still recommends that most anorexics be treated "on an outpatient basis". It is also a damning indictment of a culture that persistently fails to take the emotional distress of young adults, and particularly young women, seriously.

Anorexia is not a fashion statement or a lifestyle choice, but a psychological breakdown that leads to physical collapse. We can no longer afford to ignore the subtlest and most deadly of mental illnesses.