The government has announced plans to make sex education compulsory for pupils aged five to 11, dividing faith groups and safer sex campaigners.

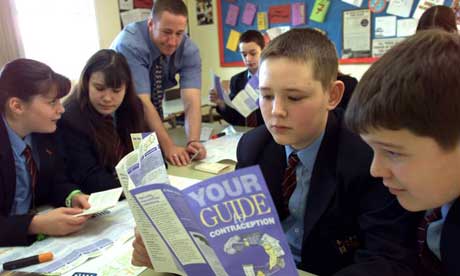

Under the plans all secondary schools will have to teach teenagers about contraception, safer sex and relationships, but faith schools will also be free to preach against sex outside of marriage and condoms.

Details of how personal, social and health education (PSHE) will be made compulsory, published today, include a clause allowing schools to apply their "values" to the lessons.

It means that all secondary schools in England will for the first time have to teach a core curriculum about sex and contraception in the context of teenagers' relationships, but teachers in faith schools will be free to tell them that having sex outside of marriage, homosexuality or using contraception is wrong.

A government-commissioned review by Sir Alasdair Macdonald, headteacher of Morpeth school in east London, on how to make PSHE compulsory between the ages of five and 16 sets out how schools will be legally obliged to teach pupils about health and nutrition, safety, personal finance, drugs and alcohol and sex education.

For the first time pupils will be taught about how to stay safe – from tackling cyber bullying to resisting pressure to join gangs – and how to manage their bank accounts when they grow older. But the most controversial element is making sex education compulsory, which has divided faith groups and safer sex campaigners who highlight the fact that Britain has among the highest teenage pregnancy rates in Europe.

For the first time in secondaries an optional curriculum covering sex and contraception in the context of relationships will be made compulsory – previously schools only had to teach the fundamentals of reproduction, contraception and puberty in science lessons.

A new curriculum for primary schools will include teaching five-year-olds about different kinds of relationships, managing their emotions and about physical changes to their bodies in childhood. At nine pupils will learn about "physical and emotional changes that take place as they grow and approach puberty", and by 11 about reproduction and about understanding their feelings as they enter puberty.

But faith schools will be allowed to deliver the lessons in line with the "context, values and ethos" of their religion, the report says. Parents will also retain the right to withdraw their child from sex education lessons, meaning some children will continue to miss out altogether.

Macdonald acknowledged that giving schools the right to apply their values was "difficult" and could conflict with the curriculum.

He said: "What we're trying to do, and I accept it's difficult, is find a balance between young people having an entitlement to knowledge, facts, information but where schools, particularly schools with a particular faith interest or other disposition, also have a right to put that in context of their particular institution. Parents have chosen to send a child to that particular institution knowing that will be part of the education.

"I'm not suggesting that's easy and I'm glad it's not my responsibility to do it. What we're looking for is some kind of balance between ... the entitlement of young people and how much schools have a right to put that in their context."

Macdonald's report also safeguards a parent's right to opt-out of sex education. Currently 0.04% of pupils are withdrawn from lessons, usually on religious grounds. Macdonald said that where parents withdrew their children it was up to schools to provide their parents with materials so they could cover the curriculum at home.

Headteachers are opposing the plans on the basis that they will add another compulsory element to an already overcrowded curriculum.

John Dunford, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), said: "While ASCL does not support the government's intention to make PSHE compulsory, we are grateful to Sir Alasdair Macdonald for producing such an eminently sensible report.

"The existing programmes of study in PSHE are, as the report states, fit for purpose and it is difficult to see why the government wants to turn this into a statutory requirement."

The schools secretary, Ed Balls, accepted the plans in a statement to the House of Commons and said the proposals will now be subject to consultation.

He said: "It's clear that if children are going to get a well rounded education which prepares them for life in the 21st century, PSHE has a key role to play.

"Most schools already follow the non-statutory curriculum, but current provision can be patchy. Compulsory PSHE will mean consistency and quality, so all children can benefit."