After walking into a bar on his first ever night in the USA, an aspiring actor bought a beer and settled down to watch the band. First Frank Sinatra walked in. And then the band turned out to be Louis Armstrong backed up by Billie Holiday. "So you see", says Joss Ackland with a gentle smile, "weird things have always happened to me."

In his eclectic collection of "weird" occurrences, Ackland includes the death of his beloved wife Rosemary from motor neurone disease (MND), a rare terminal illness. Affecting only 5,000 people in the UK at any one time, sufferers can feel as if they've been plucked out of obscurity for some cruel character test.

For the Acklands, it spelled the end of a 51-year love story; a story documented in its entirety in Rosemary's diary. Since her death in 2002, Joss has edited her entries into a book, interweaving his own observances of their life together. If it was an attempt to keep her alive, it worked - Rosemary's strength and peaceful nature positively sing from the pages.

"She always kept me going and she never made a big fuss about things," says Joss. "She was always quiet in the background but she was the strength behind everything.

"It was a great relief doing the diary. I was still with her. Now I find I'm lost and confused."

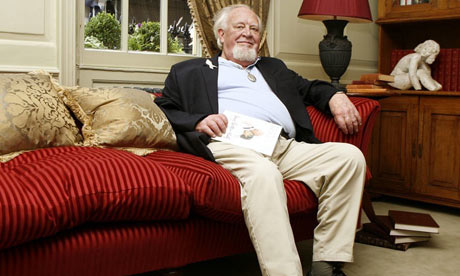

Joss Ackland cuts a commanding figure, his deep voice projecting across the serene hotel library where we meet. It is hard to believe him when he says the loss of Rosemary has left him too nervous to return to the theatre that nurtured him into one of Britain's most respected actors.

But MND is relentless in its grinding down of both patients and those close to them, and it's a shock from which it is not easy to recover. The disease is rapidly progressive in its attack on the body's motor neurones, causing muscles to waste. There is currently no cure - half of all sufferers will die, immobile and unable to communicate, within 14 months of diagnosis. Their intellect and senses will be intact.

Challenging the isolation of MND is what makes Rosemary's diaries so moving - and so important. She writes colourfully about the couple's physical relationship, which remained vibrant even when the disease was tightening its grip ("Joss came home at 1.30, and oh! - what a lovely surprise - he made love with me, and I was so elated.")

She castigates the way she is perceived and treated as a patient almost immediately, with wheelchairs and ramps disfiguring her home even before she needs them. And later on, despite her mobility problems, she still accompanies her husband on filming trips to Canada and Italy. Life certainly went on.

"My initial thought when I saw the diaries was 'this could be fun and interesting'", says Joss. "The MND thing came later as I realised it could be a really important way of getting people to notice. I don't know the effect the book will have on people because it is depressing in parts, but in others it is part adventure, part fun. And I kept the sex in because it shows life can go on, that you can still do things as you did before."

Medical science, for so long dumbfounded by MND, is beginning to make hesitant progress against the disease. The Sheffield Institute for Translational Neuroscience (SiTran), a dedicated research centre for the disease, will be completed in July 2010. It will allow experts in the field to gather their resources together and focus their energies more effectively on developing treatments.

Professor Pamela Shaw, the neurologist behind SiTran, is optimistic: "Our ability to fight MND is painfully slow but there are great opportunities. Treatments come through in a step-by-step process. We already have Riluzole, a drug that can prolong life by four months - in cancer treatment that would be a breakthrough. We have identified genes that we know now are hereditary and we are developing much better symptomatic care.

"MND is a heart-rending disease. People are touched by it if they encounter it, but it is rare and so quick that it's difficult to raise awareness."

This speed is shot through the last chapters of Rosemary's book. Months become a few paragraphs rather than whole pages; days blend into each other as dinner parties until 4.30am are replaced with four-hourly feeds through a tube. Her frustration is palpable and tensions between the couple mount.

"Joss got in a mood because I couldn't tell him what I wanted," she writes. "He threw the pad and pen away and started to cry in temper 'cause he couldn't understand." Rosemary's observations and feelings are so vivid the reader forgets that, by now, she cannot speak.

"It's important to give the patient's point of view," says Rebecca Rush, whose brother Ben Byer made the film Indestructible about his battle with MND at the age of 31. "What they go through, what their families do - people need to see it in action because this disease is much more than a paragraph in a text book."

It is a feeling echoed by Joss. "I don't feel MND changed Rosemary. She accepted everything in her life but I do feel a guilt of selfishness for wanting her to stay alive as long as possible." Through publishing her diaries, he may have got his wish.

• My Better Half and Me by Joss Ackland is published by Ebury Press, priced £18.99. Buy a copy online at the Guardian Bookshop. Joss will be speaking about the book at the National Theatre on 7 September; nationaltheatre.org.uk

'One thing I'd love to do is get drunk again'

Dino Deanus, 35, from Welwyn Garden City, has been diagnosed with MND.

When I got the diagnosis I had no clear idea of what that meant. We were so shocked. I'd never heard of MND. I don't know whether I'm more aware of it now because I have it or whether more and more people are getting diagnosed with it but I certainly hear of it more.

I was always very outgoing; I loved going to the pub and I'd always be doing something. But now, if my wife's not home, I can't do anything and it's very frustrating. I hardly ever go out. I don't feel comfortable eating in front of people because I find it difficult to swallow or hold cutlery so it can be quite isolating.

One thing I'd love to do is get drunk again! Just feel that free abandonment. I miss dancing and going to a pub and not being worried that I'll fall over. Just doing normal things. I haven't done that for over a year and I feel guilty because my wife misses it too.

Whenever you hear about MND it's always about assisted suicide. That's not particularly positive. I try to switch off and say: 'Well, I'm still here and there's people much worse off than me.' You have to be positive for what you have at the moment. You have to keep planning and looking forward to things. But having said that, I hope I know when enough is enough.

More information