For seven years the man lay in a hospital bed, showing no signs of consciousness since sustaining a traumatic brain injury in a car accident. His doctors were convinced he was in a vegetative state. Until now.

To the astonishment of his medical team, the patient has been able to communicate with the outside world after scientists worked out, in effect, a way to read his thoughts.

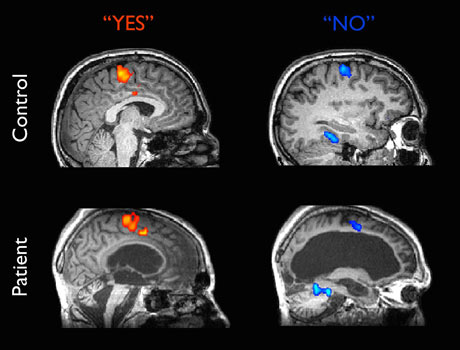

They devised a technique to enable the man, now 29, to answer yes and no to simple questions through the use of a hi-tech scanner, monitoring his brain activity.

To answer yes, he was told to think of playing tennis, a motor activity. To answer no, he was told to think of wandering from room to room in his home, visualising everything he would expect to see there, creating activity in the part of the brain governing spatial awareness.

His doctors were amazed when the patient gave the correct answers to a series of questions about his family. The experiment will fuel the controversy of when a patient should have life support removed.

It also raises the prospect of some form of communication with those who have been shut off from life, perhaps for years.

"We were astonished when we saw the results of the patient's scan and that he was able to correctly answer the questions that were asked by simply changing his thoughts," said Dr Adrian Owen, assistant director of the Medical Research Council's cognition and brain sciences unit at Cambridge University.

"Not only did these scans tell us that the patient was not in a vegetative state but, more importantly, for the first time in five years it provided the patient with a way of communicating his thoughts to the outside world."

Dr Steven Laureys, from the University of Liège in Belgium and co-author of the paper on the patient, said: "It's early days, but in the future we hope to develop this technique to allow some patients to express their feelings and thoughts, control their environment and increase their quality of life."

The patient has not been identified, but his family was said to have been happy with the outcome. "That's not unusual," said Owen. "The worst thing in this sort of situation is not knowing."

He said that as many as one in five patients in a vegetative state may have a fully functioning mind.

The British and Belgian teams studied 23 patients classified as in a vegetative state and found that four were able to generate thoughts of tennis or their homes and create mind patterns that could be read by an fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) scanner – although only one was asked specific questions.

Owen said that misdiagnosis of vegetative state was fairly common: in about 40% of cases people are later found to be able to communicate in some way.

He said he believed that the patients who responded in the study were probably "perfectly consciously aware", although he knew others would disagree.

"To be able to do what we have asked, you have got to be able to understand instructions, you have to have a functioning memory to remember what tennis is and you have to have your attention intact. I can't think of what cognitive functions they haven't got and still be able to do this," he said.

When it was suggested that to be conscious but trapped in an inert body might be a worse fate than to know nothing, Owen said: "On the plus side we are making enormous advances. Things have changed so much in the last few years."

Owen was speaking from Austria, where he had travelled for a conference on the latest in brain-operated technology – computerised devices powered by thought – which is attracting interest, including from the games industry.

"Perhaps some of these patients could benefit from some of these activities," he said. In the meantime, doctors will at least be able to ask patients if they are experiencing pain.

The paper, published tonight in the New England Journal of Medicine, generated immediate excitement.

"These findings have broad implications, not just for concerns about the accurate assessment of vast numbers of patients in custodial care situations, but in the context of any clinical encounter where we currently rely on behavioural assessment alone to identify consciousness," said Dr Nicholas D Schiff, associate professor of neurology and neuroscience at Weill Cornell medical college in New York.

He called for urgent efforts to identify and help such patients.

"The most important question left unanswered by these findings is what mechanism accounts for the stunning dissociation of behaviour and integrative brain function. I think we can be sure that as the biological answers underlying this question become more clear this will have a profound impact across medicine."

Professor Chris Frith, of the Wellcome Trust's centre for neuroimaging at University College London, said Owen and his colleagues had opened the way to communicating with patients in a vegetative state.

"It is difficult to imagine a worse experience than to be a functioning mind trapped in a body over which you have absolutely no control," he said.

"Obviously, more technical development is required, but we now have the distinct possibility that, in the future, thanks to Owen and colleagues' work we will be able to detect cases of other patients who are conscious, and what's more, we will be able to communicate with them."