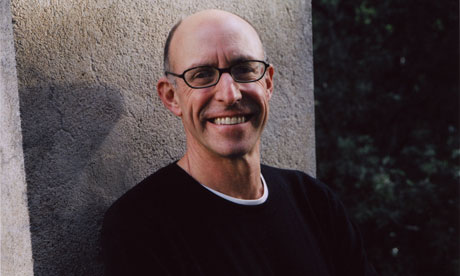

Michael Pollan, tall, fit, not quite skinny but very definitely lean, is holding a fruit yoghurt in one hand and a bottle of Coca-Cola in the other.

"So," he says, "which do you think, per 100 grammes, contains more sugar?" The Coke, I reply. Duh. "Wrong," he says. "The yoghurt. And look, it's low-fat. Isn't that great? We're getting fat on low-fat food."

It's a nice illustration of Rule Nine in Pollan's magnificently sensible new book, Food Rules. Along with such gems as "Don't eat anything your great-grandmother wouldn't recognise as food," "avoid food products containing ingredients no ordinary human would keep in the pantry," and "don't get your fuel from the same place your car does," Pollan recommends: "avoid food products with the wordoid 'lite' or the terms 'low-fat' or 'non-fat' in their names."

His reasoning: if you remove the fat from a foodstuff, it doesn't necessarily make it non-fattening. Certainly not if the producer ratchets up the sugar content to compensate for the flavour that vanished along with the fat. In fact, Pollan notes, since Americans - and hence most of the rest of us in the west - began producing and eating low-fat food products, we've actually been consuming up to 500 extra calories a day. Brilliant.

Pollan, award-winning author, journalist and campaigner, is on a mission. Food Rules is, in effect, a condensation of his previous work: much of the science behind these 64 simple, deliberately catchy injunctions ("The whiter the bread, the sooner you're dead") towards a healthier diet made up of real, honest food has already been expertly - and readably - dissected in works like The Omnivore's Dilemma and the US bestseller In Defence of Food.

The Rules spring from two unarguable facts (facts so unarguable, in fact, that even the biggest food multinational would have trouble contesting them). The first is that people who eat what Pollan defines as a Western diet ("lots of processed food and meats, lots of added fat and sugar, lots of everything except vegetables, fruits and whole grains") tend to suffer from Western ailments: obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

The second is that people who don't, people who eat more traditional diets - including diets like those of certain indigenous peoples which by the lights of Western food science might be considered way too high-fat, high-carb or high-protein - do not tend to suffer from these diseases. In other words, human beings can cope with, can indeed thrive on, a wide variety of foods and diets, with one major exception: the diet most of us in the west are now eating.

So why are we all eating ourselves to death? Because for big food manufacturers, the Western diet is payday, every day. "The more a food is processed, the more profitable it gets," says Pollan. And that status quo is not challenged by modern food science, which is all about identifying the "good" and "bad" nutrients in processed foods and tinkering with them - by lowering the fat, for example, or boosting the vitamins - rather than questioning the value of processed food products in the first place.

"We don't talk about food any more," says Pollan. "We talk about nutrients: omega-3, antioxidants, saturated fats, polypenols. And so we play into the hands of the food marketers - it all becomes one great big beautiful game."

The world of processed food, he observes, is truly a marketer's dream: "You can tweak it, reformulate it and reposition it ad infinitum. And every time, you make money." (Which explains Rule 11: "Avoid foods you see advertised on the television". Simply, since only the biggest food manufacturers can afford TV advertising, and more than two-thirds of TV food ads promote processed foods, declining to buy any food product backed by a big advertising budget means you're unlikely to ingest what Pollan charmingly terms "edible foodlike substances".)

This all has the crushing logic of truth. Can we do anything about it? The real food movement, Pollan concedes, is up against "incredibly powerful" interests: multinationals smart enough to see which way the wind is blowing, and present themselves as part of the solution. "My Rule Six," he points out, "is: Avoid food products that contain more than five ingredients. Haagen-Dazs just launched a new line. Know what it's called? Five. It's still ice-cream, though."

He has little faith that Big Food will change voluntarily: legislation will be needed, he fears, although he takes heart from the Obama administration's recent victory on healthcare reform. "Pretty soon," he explains, "the insurance industry is going to realise that we're going to have to tackle obesity and type 2 diabetes. They might even come out in favour of taxes on soft drinks. And once we see one powerful industry pitted against another, then we might see progress."

But the complication of food has been under way for a long time now. The process, launched in Britain back in the 1800s thanks to the slave trade and the industrial revolution, really took off, Pollan reckons, after the second world war, when we "emerged from years of rationing - so ready to binge on sugar, meat, white flour - just as industry was converting from making bombs to making fertiliser, and nerve gases to pesticides."

Agriculture suddenly got way more productive, so "corn and soy and wheat and rice got cheaper - and the only way to make money out of them was to process them. A sort of arms race started to make food more complicated: Don't buy flour, buy cake mix; don't buy cake mix, buy cakes. Don't buy oats, buy Cheerios; not Cheerios, cereal bars." Not to mention, of course, our own fatal attraction to the three cheapest ingredients of all: sugar, salt and fat.

The fightback began to take hold with food scares like BSE, and is being further bolstered by mounting environmental concern: Big Food as it exists today is, patently, not sustainable. Two shocking statistics: before 1950, every calorie of fossil fuel energy expended on food production resulted in 2.3 calories of food; these days it takes 10 calories of fossil fuel energy to produce one calorie of your edible foodlike substance.

Is that process reversible? It may have to be, Pollan argues, as we start running out of fossil fuels. He's sure we can produce enough real food to feed us all, but fossil fuels will have to be replaced by manpower. "Organic farms are wildly productive," he says, "but a lot more labour-intensive. That's why we shouldn't be exporting technologies to the developing world that will take people off the land. We're going to need more people on the land, everywhere."

So convincing is Pollan's logic, so practised his arguments, so impassioned his presentation, that you wonder where it all came from. He started out, he says, as more of a naturalist than a foodie, but was gradually won over by the notion that "what happens on our plate actually represents our most powerful engagement with the natural world". So does he practise what he preaches?

Certainly, he can no longer - knowing what goes into it - eat junk food. (His teenage son, to his regret, can, but is apparently beginning to realise it may not be altogether as good by the end of the bucket as it seemed to be at the beginning.) "I love good food, I love to eat," he says.

"But while I've had my share of meals in temples of molecular gastronomy, I'm not over-keen. For me it tends to get in the way of community, which for me is key to good eating. It's worth noting, in that context, that shared food flies in the face of the food industry's interests: the more they can subdivide the family, make sure everyone eats something different, the more money they make."

He acknowledges, though, that many of the exchanges he has about this whole issue "are with skinny people." An interest in good and healthy food is, still, something of a middle-class preoccupation. "But abolition, women's suffrage, those movements began as elitist too," Pollan says. "It's too soon to say whether radical change is possible - the real challenge, in the end, is finding ways to make money selling simple foods. But if this movement does what most movements do - shifts the centre just a few degrees - then that will already be progress. I won't be discouraged."