It seems the government has moved on from higher education and on to our higher feelings: it is proposing to measure our happiness. But, as centuries of philosophical debate have shown, happiness is neither simple nor uncontroversial – and certainly not easy to measure.

In the western philosophical tradition, reflections on what the best kind of life might be have almost always acknowledged that happiness is something we all desire. Philosophers often regard human happiness as an important criterion for deciding what is good and right, and sometimes as the main criterion. The most straightforward expression of this last view is found in the "utilitarian" moral theory pioneered in England in the 19th century by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill.

According to utilitarians, the moral value of any action is measured according to the amount of happiness that results from it. Even for these thinkers, though, questions of happiness are not simply about how much of it there is. Mill certainly recognised different qualities of happiness: he thought that the pleasures of listening to opera or reading Milton, for example, were "higher" than the kind of enjoyment found in a good meal. Indeed, he famously qualified his utilitarianism by insisting that "it is better to be a Socrates dissatisified than a pig satisfied". The thought here seems to be that part of the moral value of human life – what we might called its dignity – lies in the capacity to be affected by a great range and depth of experience. And this includes our capacity to suffer.

Critics of the kind of moral theory advocated by Bentham and Mill often talk about the practical difficulties of measuring happiness, which might give the coalition pause for thought. In fact, some of these difficulties were pointed out long before the rise of utilitarianism. Aristotle, for example, thought that the goal of every human life is "eudamonia", a deep conception of happiness as long-term flourishing, rather than fleeting pleasure. This would be difficult, if not impossible, to record with questions such as "how happy did you feel yesterday?".

Aristotle also recognised that, unlike some other branches of philosophical enquiry, ethics is not an exact science. In the 18th century, Immanuel Kant made this point even more strongly: of course we all desire happiness, said Kant, but we do not know what it is or how it will be achieved. Anyone who has pursued something in the hope that it will make her or him happy – whether this be a career path, a relationship, or a holiday – only to find it disappointing, and even a source of stress and anxiety, will know what Kant was talking about.

However, the government's plan to measure happiness raises a further and perhaps more profound philosophical question: regardless of whether this is possible in practice, is it the best way of thinking, even in principle, about what it is to live a good human life? A clue to this idea can be found in the way a term like "utilitarian" is sometimes used disparagingly. When, for example, a course of action is described as "merely utilitarian", this implies that something important has been overlooked. But what might this be?

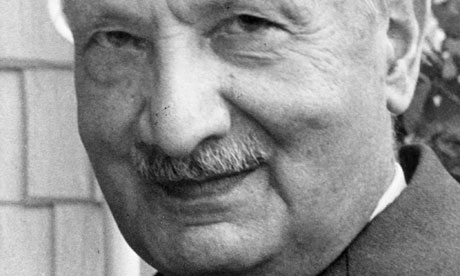

The German philosopher Martin Heidegger can help us to answer this question. In his work both before and after the second world war, he came to focus increasingly on the issue of modern technology. He argued that technological devices such as machines and gadgets were symptoms of a deeper phenomenon that could be traced back through centuries of western culture. "Technology" in this deep sense refers not to this or that item of equipment, but to a fundamental way of thinking, and of being, that shapes everything we do.

The essence of technology, argued Heidegger, lies in the idea that life is something to be controlled and mastered. Instruments of measurement and calculation – surveys, for example – are integral to this project. Heidegger linked the accelerating domination of technology in the 20th century with the idea that modern humanity faces a spiritual crisis. According to this view, utilitarian approaches to ethics in general, and attempts to measure and regulate happiness in particular, are symptoms of this crisis rather than solutions to it.

Heidegger's analysis of technology expresses in secular terms ideas that have recurred through religious traditions over many centuries. These traditions aren't immune to ideals of mastery and control: the bible teaches that man has dominion over nature, and the "spiritual" exercises taught by ancient Indian sages were – not so unlike modern drugs – techniques to alter and regulate states of mind and body. But these religious forms of technology exist alongside a willingness to recognise the limitations of human power and control, and the need to be receptive to something beyond ourselves.

This isn't to suggest that we can't be responsible for our own actions, and also for our own flourishing. Denying our responsibility would itself be morally and spiritually – as well as politically – dangerous, and this is certainly not what Heidegger's philosophy of technology, nor traditional Christian theology, are advocating. Our government seems to be struggling to strike the right balance between individual and collective responsibility – and it is sometimes hard to avoid the suspicion that its emphasis on both personal responsibility and "big society" is seeking to mask and allow a disavowal of public responsibility.

As our pens hover between the "fairly chirpy" and "very disgruntled" boxes on the new household survey, we might pause to reflect on these questions of happiness and responsibility. Perhaps the wisest people are those who make every effort to establish and maintain the conditions of their happiness: health, wealth, friendship, a clear conscience, and, yes, perhaps a decent single malt in the cupboard. (At least some of these conditions can and should be promoted by the state as well as by individuals.) At the same time, though, they recognise that happiness cannot be engineered, for it comes and goes, more like a gift that is given than a commodity that is produced. Such people do what they can to protect against the vicissitudes of fortune, while remaining open to those moments when they are surprised – maybe even in the midst of grief or cancer or redundancy – by the joy of an unexpected call from an old friend, or a hedgehog ambling across the garden, or a crisp bright November day.