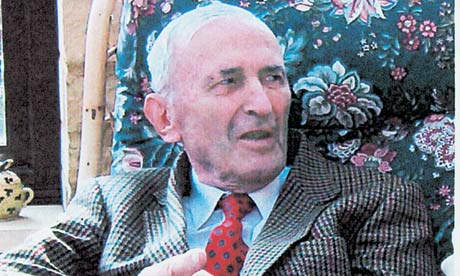

Wolfgang Lutz, who has died aged 97, was a doctor who investigated the links between nutrition and health. Concerned over the dramatic escalation in what he termed the "diseases of civilisation", he developed the idea that humans are insufficiently adapted to the comparatively recent high-carbohydrate foods of the Neolithic age. He suggested that a diet similar in composition to that of the Ice Age hunter-gatherer might be more suitable to our genome. He recommended a "modern Paleolithic diet", unrestricted as to protein and fat, yet low enough in carbohydrate to be compatible with our genetic inheritance.

Wolfgang further surmised that the pattern of our hormonal secretion must be tuned to the largely animal diet of that distant epoch. He demonstrated clinically how today's comparative overload of carbohydrate requires compensatory adjustments in our hormonal secretions – primarily in insulin, but also in thyroid, adrenal, growth and sex hormone levels. Wolfgang was the first to describe how these often prolonged disturbances in hormonal regulation could underlie many of our modern diseases.

He wrote up his findings in books and more than 60 articles. His Leben Ohne Brot (1967) is now in its 16th edition and was translated as Dismantling a Myth: The Role of Fat and Carbohydrates in Our Diet (1986). Life Without Bread (2000), written jointly with Christian Allan, was published in the US.

The son of a general practitioner, Wolfgang grew up in rural Austria; and read medicine at the universities of Innsbruck and Vienna. After graduating, he joined the staff of the Second University Medical Clinic, in Vienna, but the second world war interrupted his research. Focusing then on the medical aspects of aviation, Wolfgang was able to determine that, when pressurised cabins fail at high altitude, it is a sudden drop in pressure that causes pilots to lose consciousness. Working on small animals, he invented a prototype space suit, which automatically inflated the moment oxygen pressure dropped by a critical amount.

Wolfgang, unwilling to carry out experiments on humans, as he was requested to, changed field and a second remarkable discovery followed. Spotting that, when emerging from a frozen state, the brain woke earlier than the heart, Wolfgang developed resuscitation techniques that helped save the lives of pilots rescued from freezing Arctic waters. He hoped his technique might also help in heart surgery.

After the war, he rejected an offer to work in space technology in the US; then, his name having been cleared, he attended the Nuremberg trials as a witness and, in 1947, he became a practising physician. In 1968, he moved into private practice in Salzburg, where he remained until his "retirement" in 1992. In later years, he divided his time between Graz and London. Among other honours, he was made chancellor of Dublin Metropolitan University in January 2007 and that May was given the freedom of the City of London.

As an occasional translator and writer, I knew Wolfgang for 15 years: he was a man of charm, humour and courage, always accessible to his patients, and with the tenacity to pursue and check an idea for half a lifetime.

He is survived by his wife, Helen, and five children.