One in every eight women will get breast cancer in her lifetime. The risk used to be one in nine, but the disease is gaining on us, according to new statistics from Cancer Research UK. How many of us counted the heads of little girls in the playground on hearing the news, or glanced speculatively around a bus or train carriage at the other female passengers? How many of us wondered if we ourselves were destined to be the unlucky eighth?

Breast cancer is being increasingly diagnosed – of that there is no doubt. But the picture is not as bleak as the headlines might suggest. For a start, it is not the little girl in primary school who has a one-in-eight risk of breast cancer – it is her grandmother, who has turned 70. Second, we can all do something to reduce our individual risk of getting the disease. And third, breast cancer is now a disease that most women survive, thanks to earlier diagnosis and better treatment.

Cancer is largely a disease of old age. Young women such as Kylie Minogue are the exception, not the norm. That's why screening begins at the age of 50. Age, says Julie Sharp of Cancer Research UK, is "by far the most important risk factor".

At the age of 29, in fact, the risk of breast cancer is only one in 2,000. At 39, it is one in 215 and at 49, when the invitation to breast cancer screening is about to drop through the door, it is one in 50. It is not until a woman reaches 70 that Cancer Research UK offers a "lifetime risk" of one in eight. But the risk of hitting quite a number of health problems, one might say, goes up substantially beyond the age of 70.

Sharp says this is why screening is so important. "You can't do anything to turn the clock back, but it does mean, in older women, that it is really important you go for your screening appointment," she says.

Screening, though, may be part of the reason behind the rise in breast cancer cases: more are being detected in older women. "It is possible that part of the increase could be due to the fact that the screening age has been extended to 70," says Sharp. Until 2006, the cut-off point was 64.

It may be one of the factors, but it is not all. Interestingly, the increase in lifetime breast cancer risk calculated by Cancer Research UK (CRUK) did not happen in 2008, as implied in the press release and assumed by every news organisation. It changed between 2002 and 2003.

Behind the figures is a change to the methodology used in the past. In an as-yet unpublished paper, Peter Sasieni, of the Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine at Queen Mary's in London, and his colleagues have devised a way to the end the "double counting" that meant women who had a second cancer in the other breast were counted twice. So in past years, lifetime risk calculations were based on the number of cancers, not the number of women. CRUK's own statisticians have used this new methodology to produce their figures. They show that lifetime risk increased from one in 10 to one in nine in 1997, not 1999, and from one in nine to one in eight in 2003.

CRUK says a number of things may have contributed to the rise, from having fewer children to lifestyle factors such as increased drinking and obesity. Press coverage suggested women could do more to lessen their own risk of breast cancer by improving their lifestyles. These had an unfortunate impact on some women who have already been diagnosed. On the discussion forum of Breast Cancer Care, a charity that supports women with the disease, some said they were being made to feel guilty. "The line has stimulated a great discussion among users who felt the coverage was blaming them for their cancers," says Jackie Harris, clinical nurse specialist with the charity.

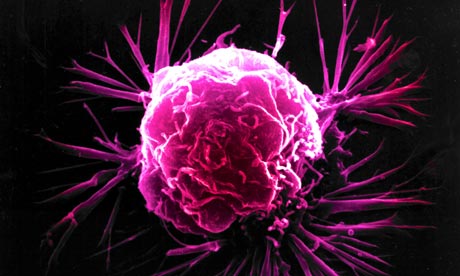

The three main risk factors, she says, have nothing to do with lifestyle. They are age, being female and having a significant family history. And only those with the few genes closely associated with breast cancer can be fully aware of their own risk. "For anybody else, it is a complex disease," she says. "At the end of the day, all cancers are genetic, but they need other triggers in lifestyle and the environment."

Many of those triggers have been identified. We know that women in developing countries, who start to have babies at a much younger age than us in the west and have more of them than us, have lower rates of breast cancer. Oestrogen and other hormones are strongly implicated in breast cancer, and both pregnancy and breastfeeding suppress ovulation, thus reducing the amount of circulating hormones. According to the Oxford collaborative group on hormonal factors in breast cancer in 2002, each birth decreases the risk of breast cancer by 7%. Every year of breastfeeding cuts the risk by 4.3%.

The cultural changes in affluent societies that have led women to have fewer children, later in life, are not going to be unpicked in a hurry. But there are other risk factors that we could do something about. The Million Women Study, a massive project based at Oxford University and funded by CRUK, has identified some of them.

A series of questionnaires to the 1.3 million women who enrolled when they were first called for breast screening has probed their lives, their backgrounds and their behaviour. The responses have implicated alcohol – a small daily glass of wine increases breast cancer risk by 6%. Carrying excess weight after the menopause is also a risk – body fat pumps out oestrogen and other hormones, which have an effect on the way cells grow and divide. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) increases risk, which means that women who take it will need to balance the breast cancer risk against the sometimes distressing and debilitating symptoms of the menopause.

On the plus side, exercise really does appear to reduce the risk of breast cancer. "It is important to keep active," says Sharp, "partly to keep the weight down, but people are also looking at whether physical activity affects hormone levels."

There is evidence implicating some foods, such as red meat, in some cancers. Bowel cancer, for instance, is linked to diet. But as yet, there is no good evidence that diet affects breast cancer.

Harris, of Breast Cancer Care, says there is no harm in trying to live a healthier lifestyle, but warns it is not certain to protect you from cancer. Eating well and drinking less and exercising are all good for your health, she says, "but doing that is not a guarantee it will stop you getting breast cancer. A lot of women [who come to the charity for support] haven't drunk. They have had their babies early. They breastfed." These women, she says, felt that the media coverage making a big issue of lifestyle "was very much blame-centred".

It's easy for women toget anxious over breast cancer, she says. In 1991, the message that used to go out to women to examine their breasts for changes regularly was changed. Advocates instead began talking about "breast awareness". Some women, feeling for lumps once a month or more, would believe they hadn't done it properly if they hadn't found anything. "It increased anxiety and over-investigation. We want people to look and feel, but not be prescriptive about when to do it."

She feels women should work on a healthier lifestyle if they want to, but not at the expense of the quality of their life. "Statistics are good for a population, but what do they mean to an individual?" she says.

Each one of us has an individual risk, but we are unlikely to be able to find out what it is any time soon. Scientists are looking at genetic patterns that may predispose us, but it's a far more complicated business than finding the big single breast cancer genes BRCA 1 and 2, which give some women a very high likelihood of the disease.

Women who have a family history of the disease, even though they may not be carriers of BRCA1 or 2 themselves, may run an increased risk and should talk about it to their GP, say breast cancer advisers. They may be referred to a family history clinic or a regional genetics centre, where experts can work out any potential risk, which will be different depending on factors such as the age at which relatives got the disease and whether they were on the maternal or paternal side of the family.

Without exact knowledge of one's risk, we have to guess at the likely impact of our healthy or unhealthy habits. A 6% increased risk from drinking a glass of wine a night is maybe worth taking if you have only a 10% risk of breast cancer to begin with – 6% of 10% is very slight.

What probably matters most is our general state of health. People who drink too much and eat too much and never so much as run for a bus risk not only breast cancer but a whole load of other diseases too, which may well kill them long before they reach the age of 70.