"What a pity it's not a sin!" says a woman licking an ice cream in a story by Stendhal, reminding us that the search for pleasure – and prohibited pleasure at that – is a primary preoccupation for most people a good deal of the time, even for those trying to hide from it.

Even reading the Kama Sutra, in a fine new translation by AND Haksar, feels like a guilty pleasure. In the mid-60s, when I first heard of it, the Kama Sutra was, along with The Perfumed Garden and Venus in Furs, considered licentious and filthy, the very gateway to damnation. In the London suburbs in the early 60s, if a young man sought knowledge of sexual matters he had to traipse up to the West End to watch European films, and if particularly desperate during a tiresome evening might even be forced to turn to literature. My father owned copies of contraband such as Lady Chatterley's Lover, Lolita and other such serious stuff, along with Harold Robbins. The real business, for me, was in the Robbins, and I ended up never reading the Kama Sutra. And the longer I didn't read it, the more dreadful this famed carnival of desire and mayhem became in my imagination.

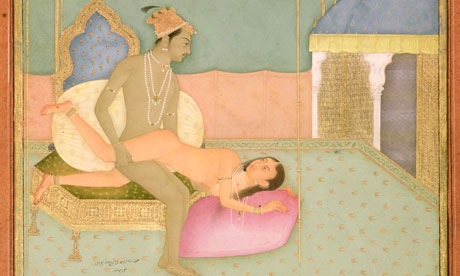

It turns out that Kama Sutra: A Guide to the Art of Pleasure is a compendium of advice about social and romantic behaviour, put together 1,600 years ago, for wealthy young men about town. It contains information about hygiene and sexual positions, and advises how not to cause havoc in a harem, how to deal with courtesans and how to behave towards "the wives of others". It suggests that the gentleman should keep away from lepers, malodorous women and anyone with white spots. It is arch, comical and amazing – less Byron and more the sort of thing that Jeeves would have said to a priapic Bertie Wooster had Bertie been Indian and PG Wodehouse without the sense to omit sex from his books. It states, for example, that "intercourse with two women who have good feelings for each other is known as the 'combination'. The same with many women is called 'the herd of cows'." Although the Kama Sutra doesn't take pleasure seriously enough to be wise, it is certainly a reminder of the central place of sexuality and its pleasures in our lives, and pleasures, as every parent knows, have to be both limited and passed on to the next generation. They are, then, mostly transmitted by being forbidden, and it is this relation to prohibition that amuses and intrigues Stendhal. It is prohibition that makes serious recreation feasible, just as it is the rules that make sport possible. Without authorities or taboos there isn't more fun, but more nothing, particularly as we tend to treat ourselves more severely than even the authorities do.

The Kama Sutra, as a book of technique – a sexual self-help manual for the socially naive, a way for geeks to make it with girls – is fascinating, therefore, in what it omits. It neglects, for instance, one of the most important parts of love: that one can caress with the voice as well as with the eyes.

In fact, its routines appear to render any form of sensual transaction uncreative, predictable and controlled, and the male omnipotent. If it turned out that the woman was also consulting a similar manual then the two characters in this drama would be playing roles that would ensure they'd remain outside the experience. Both would be in a fixed place and the relationship would merely be an exchange of fantasies. The interesting question here is whether this is perhaps the truth about sex – whether a Clintonesque "I did not have sexual relations" seems to get it right, and there is really no touching, ever – or if this is wishful thinking. Like Alfred Kinsey's reports at the end of the 1940s and early 50s, the Kama Sutra tries hard to turn passion into science.

One can see why. The minor pleasures may be satisfying and even fulfilling, but the major ones are serious toil. That sex is chaotic, mad, perverse, risible, enlivening and inspiring, and that in its awkwardness and self-consciousness there might be more real contact than in the simple following of positions, doesn't occur to the author. If you'd never heard of sex until you read the Kama Sutra, you'd believe it was a trickle rather than a torrent, a conversation rather than an argument, a pastime rather than a life-saver.

It's easy to praise happiness. Apparently you can't have too much of it, and, like a lovely day, there aren't many people who have a bad word to say about it. Things look even worse for happiness now that politicians have begun to take an interest in sponsoring, measuring and even trying to roll it out to the public. But you won't find pleasure on the school curriculum; it comes, as Emma Bovary would have attested, in numerous dark shades.

About pleasure there is always, and should be, dangerous ambivalence. Too little of the devil's sport and life will seem attenuated, heavy and slow, if not dead. The negative of pleasure, or perhaps its antidote, is depression, the popular modern malady, an uncomfortably dull refuge from the question of pleasure and how much is the right amount for you. Most self-help books these days are either about depression, happiness or creative writing. Pleasure is barely a topic for the pseudo-shrinks or for anyone, as if it's too dangerous to talk about – unless it's in the negative. After all, enjoyment might feel, as Baudelaire puts it, like this: "The unique, supreme pleasure of love lies in the certainty of doing wrong." Happiness is earned; pleasure is always stolen. We are more likely to envy others' pleasures than their happiness – in fact, pleasure is the only thing there is to envy.

The return of religious fundamentalism in its numerous guises is witness to the necessary presence of sin, the horror of pleasure and the desire for its strict regulation. Fundamentalism, and the obedience it enjoins, is an attempt to abolish the conflicts that pleasure involves. But in such circumstances the pleasure of self-deprivation – religious obedience, dieting and other forms of abstinence – can come to replace genuine enjoyment. Pleasure can be slutty: it's a parasite that can attach itself to anything.

Whatever the manuals might say, and despite the rules of dating as laid down in the Kama Sutra, obviously there can't be a right answer to the question of the right amount, though there is much anxiety about the wrong amount. Certainly, if there is too much pleasure – if one hates or loves too much – there might be addiction, madness, violence, disappointment and the sacrifice of oneself and others. Pleasure can smash things up; you could die or kill for it, and people do so all the time. Where happiness is its own quiet end, pleasure creates consequences: it's where the moral stuff starts.

There's nothing like a self-help book to make you feel a failure. But if someone really wants pleasure, and if they want obscene outrage more than they want contentment or safety or even happiness, the pleasure guru will have to act the minor Mephistopheles and let on that the price of the real thing could be high.

A genuinely useful self-help guide to bearing pleasure might have to contain advice about putting up with the envy, contempt and hatred of oneself as well as of others, along with any self-disgust, guilt and punishment that may follow. It would be an education in determination and ruthlessness and, to a certain extent, in selfishness and in forgetting. Inevitably, one of the lucky ones, a well-informed character in the Marquis de Sade's The 120 Days of Sodom, has the right idea: "I hate virtue and never will I be seen resorting to it. I have no need to thwart my inclinations in order to flatter some god."

He's fortunate enough to believe the law doesn't apply to him. But in Sade, as in all perversion, and to a certain extent in the Kama Sutra – despite the declarations of liberty – there's no freedom for the participants to escape the limited repertoire of roles their fantasies assign them, or to be altered by one another. Pleasure is more contentious, difficult and subversive, both emotionally and politically, than these authors want to see.

However, the Kama Sutra does usefully demonstrate that sexuality is usually in excess of our ability to process or speak about it. Such enjoyment overwhelms, and we have to give ourselves up to it, forfeiting fantasies of control, which is why words fail, and literary descriptions can seem inadequate, amusing and foolish. Expressions such as Vatsyayana's "the sparrow's frolic" and the "bull's stroke" can hardly be expected to speak to us now, and pornography, of course, is incapable of describing the inner lives of sexual beings. Compared with the actual experience, words never seem to get close to the object, but stand around looking daft.

This may be because there is no mystery left in sex. We have seen everything at least twice and are jaded. But since most of the world is more constrained than this little plot of land in western Europe, the notion of sexual freedom, pleasure and desire, particularly for women, always deserves discussion. For illustration it's the poets and sometimes novelists who can occasionally pin sensuality to the page. Nonetheless, portraying bliss is almost impossible work, and it's in soul music – in Billie Holiday, Marvin Gaye, Aretha Franklin and in some R&B – where you can see, and feel, how desire, longing, loss and fulfilment can be compacted, having a tangible effect on the listener, making them want to cry or dance.

It might be important to recognise that our pleasures have to be guarded from our own aggression, much as our freedoms are. You can make a cult of destructive pleasures, and you can devote your life to their daily deathly temptations, as many people have – "I need a danger to be safe in," writes Frederick Seidelcorrect.

But those who are afraid of the fire will want to value enjoyment as a source of illumination rather than as something that can be stared straight at. Kant defines pleasure as "the consciousness of vital effort". It is an afterglow, that which follows from something else, as one chases one's desire into solid, reasonable things – conversation, friendship, teaching, and in the erotic connections of creativity.

This is reassuring; however, the glow rather than the stare is not quite the real thing. But if you're reading the Kama Sutra you're not near the real thing either, nor is it likely to get you closer. Whichever way you like to take your pleasure, a faulty map will never guide you to your destination.

Hanif Kureishi's Collected Essays are published by Faber