We have just had a visit from our old friends, Jill and Dan. They are a remarkable couple. She was left a paraplegic after a motorbike accident 52 years ago. What a dire prospect for an active girl still in her teens! But she went on to be married, despite family pressure, to Dan, who lived in the same village. She wanted to have a family, and it of course seemed she'd have to have a baby by Caesarean section. In fact she was the first paraplegic to have a natural birth, watched by doctors from around the world, and went on to have two more boys. After their first was born, Dan was told: "You know, paraplegics normally survive just 10 years."

As for Dan, when we first met him 22 years ago, he'd been diagnosed with leukaemia and given six months to live. Then a new consultant came who agreed to break the rule of no bone-marrow transplants for over 50s. It was a sensible rule on money and outcome grounds, but Dan was basically a fit man. So he was given the transplant and a few years later a leucocyte infusion. He's still, I believe, the oldest surviving man to have had the procedure. He's the one survivor of five at that time. Life's not been easy for them, and it isn't. But they are full of life and affection.

I couldn't help reflecting how different their, and therefore their family's – and indeed our own – life would have been if the brave new world of Dignitas and its promoters had arrived here in Britain. Jill, a keen horsewoman, unable to walk, let alone mount her horse; the young woman dreaming of having four children – dropped by her boyfriend, before linking up with Dan – having her dreams dashed. Can't you imagine her being depressed, wanting to end it all? "It's my life; what future have I got? It's my choice. I want to die, now." And then years later Dan being told: "We can't cure you. Within six months you'll be dead. It won't be very pleasant. But we can offer you this shortcut treatment, which will relieve all the suffering for you and the heartache for your family. But it's your choice." "What's that?" he asks. "Oh, only doctor-assisted suicide. It's easy and pain free." No pressure! How different and much poorer history would have been if the brave new world we saw promoted on BBC2 on Monday night were here.

Jill and Dan have had and continue to have a full life. They're fun to be with and they live busy, normal (one forgets how extraordinary it is living with Jill's disability, day in day out) lives. They actually enrich you in knowing them. I expect that they would say that, having determined to live, their experiences have enriched them. It might have been so different. But they trusted it would be well. What was it that Mick the cabbie said on last night's programme? "I decided to give it one more throw of the dice." For him the hospice had given him a new lease of life.

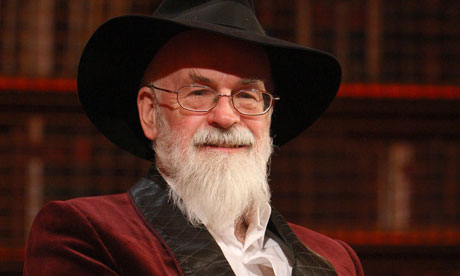

In truth, he wasn't the subject of Terry Pratchett's creative documentary, Choosing to Die, last night. It was, of course, carefully crafted and mildly poetic. We saw Alpine vistas, lakes and snow-scapes – vaguely like a travel brochure. We saw close-ups of emotional faces, even tears. We had the swelling strains of Elgar to mark the death of Andrew Colgan, a 42-year-old man with MS. And an inability to face the moment of death itself (about which I'm glad), although we had pretty much everything else around that. Despite Pratchett's resounding declaration: "I've been in the presence of the bravest man I've ever met," it left a bitter taste in my mouth as if we'd been served a cocktail of death disguised as an elixir of life.

I've been thinking about that accolade of "bravery" and it occurs to me that there was only superficial examination of motivation. There was an unchallenged assumption that MND (and MS) would lead to intolerable suffering and indignity. As I've observed in the past, that was one of my own early concerns – until an association visitor told me it needn't be the case. But one had the impression that Peter Smedley, who chose to end his life after being diagnosed with MND, wanted to avoid the later stages of the disease because he'd always been strong and in control. And actually he was afraid of losing control. Certainly someone I know with MS is terrified of "not being in charge". "I want to be able to choose," she says. And that, of course, is Pratchett's line: "My life, my death, my choice" – falsely premised though it is, for who chooses their life, who chooses to be born?

One might more charitably guess that both Smedley and Colgan wanted to spare their families the pain of caring for them and watching them through the latter stages of their lives. Yet this didn't appear to be their motive. Neither Smedley's wife nor Colgan's mother wanted their loved ones to take their own lives. They, it seemed, would have chosen to care for them to the end, as Pratchett's wife for him. In my view, the true badges of courage belong to the women who sacrificed their wishes and their instincts to their loved ones' demands. To be there to witness their unnecessary and undesired deaths, just for the sake of the other, that was real bravery. Gallantry awards are won by men and women who risk their lives for others. I don't think we saw that in the men last night. I think we saw people who were afraid of what might lie ahead for themselves and decided to face the lesser of two monsters.

And that, I believe, is the tragedy of the film and of the campaign that lies behind it. The repeated refrain, especially in the Newsnight discussion that followed, was "It's my choice", "It's his choice". There was a sort of pre-suicide litany: "Is this your choice? Do you understand what you're choosing? Do you want to take this mixture which will put you to sleep and kill you? Are you sure?" The resigned women in the end could only say: "It's his choice", "You must choose." How etiolated is that view of existence. My world, when all is said and done, is ME. My individual choice is sovereign. I want my kingdom. And the rest doesn't matter. The individual is the ace, trumping all else.

Well, that's a pretty impoverished world. In fact, interdependence is the secret of society. We are dependent on each other, and that's something for celebrating, not fearing, for embracing, not avoiding. Perhaps the city is an image of heaven because community is the heart of human existence. The best thing in life is to experience the extraordinary depth with which one can be loved. It's to discover the utter disinterestedness of those who love you, to find out when you can give nothing back, literally nothing but distasteful work and pain, they still want to look after you; they still care for you; yes, they still love you.

The tragedy of Peter Smedley and Andrew Colgan, it seems to me, is that they didn't trust themselves to the journey their loved ones wanted to travel with them – because if they had, the road might well have been rough, but they would have discovered, hand in hand with them, beauties of the human spirit few of us ever glimpse.