Tony Nicklinson is listening to the radio when I arrive. He's been hoisted into his wheelchair, and sits alone in a room overlooking his garden. Seeing me, he raises his eyebrows by way of hello. I introduce myself, ask how he is and tell him I've spent the afternoon with his lovely daughters. He nods stiffly. Then his eyes well up.

Tony had a stroke in 2005 and now suffers from locked-in syndrome: he's trapped inside his body, aware of everything going on but unable to engage with it. Paralysed from the neck down, Tony can't speak but he can think, hear and feel. He communicates through blinking, twice for no, once for yes.

There is no cure for locked-in syndrome, a condition most commonly caused by a stroke severing the connection between the brain and the body. The syndrome received widespread public attention in 2007, through the French film The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, based on a book of the same name by Jean-Dominique Bauby, who had been editor of French Elle magazine. Following a serious stroke of his own, Bauby was left paralysed save for his left eye, which he used to communicate by blinking at an alphabet board.

Tony recently made the headlines because of his legal campaign for the right to die. He has said, through blinking at letters on an alphabet board as Bauby did, that he is "fed up" with life.

It's not easy to imagine the frustration or the sadness unless you meet somebody with the condition. But having seen my dad go through something similar, I feel able to understand what Tony and his family are going through.

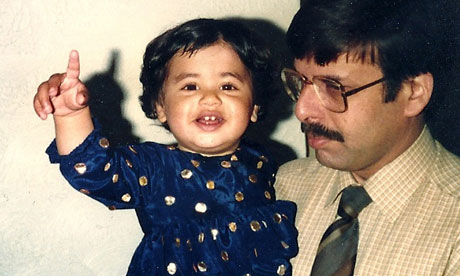

I had just turned 23 when my dad suffered the first of four consecutive strokes, each a destructive wave violently washing a part of him away. We had just celebrated my birthday together – my parents visiting me while I was studying in Paris, a fortnight before the strokes struck. It was to be the last time I saw my father well. It was the last time I took a photograph of my parents together, his arm thrown casually around her shoulder, surrounded by papery pale pink tulips. That picture, taken seven years ago and now on my bedroom windowsill, is my last memory of my dad as he was.

One evening I was revising for my final exams when my mother phoned. She told me my dad was in hospital – he'd had a stroke.

I didn't really register what this meant. I didn't know what a stroke was – I had assumed that they happened to old people, and my dad, in his early sixties, wasn't old. I did know it must be bad for my mum to be telling me just days before my finals. She said he was OK and put him on the line; he even spoke to me and said he was fine – but his voice was thick, heavy, slurred. It didn't sound like him. I put the phone down, puzzled and alone. My legs felt heavy. I knew things weren't good. Uneasily, I packed a rucksack, throwing in revision notes and a change of clothes. I imagined I'd be back soon. I wasn't.

From being the happy, healthy man in the picture on my windowsill, my father was transformed: half-paralysed, confined to a wheelchair, fed by a tube. In hospital for just over 18 months, he wasn't completely paralysed like Tony. But he gradually shut down and was still very much taken away from us, even while he was alive.

At the beginning, he could still talk, but his whispered words eventually faded to silence and sadness. He could move his right hand, and by chance we discovered he could write precious, shaky scribbles. It was my mum who figured out, later, that he could say yes or no by blinking; she picked up on it by chance, asking him if he was OK and slowly realising there was a pattern. At first, we weren't sure but the more we practised with him, the more we realised it wasn't just a haphazard movement, but a way to communicate.

The hospital months were tough. They took a toll on us all, although what we went through was not as bad as what my dad endured. Physically, we were exhausted; emotionally, wiped out. My brothers, settled in London, travelled tirelessly home to the Midlands every weekend.

My dad, the clever, funny, winsome doctor, had been my emergency call in times of panic or stupidity, my lawyer to fight my corner, my friend. At the worst of times, closer to his death, when his pain was unbearable and his body but a shell, I carried a mantra in my head – "That's not my dad, that's not my dad" – repeating it silently in my mind to remind myself of the person he was, really was, before the strokes.

My mum and I became each other's company and best friends. We spent every day in the hospital, convincing nursing staff to let us in earlier and leave later than visiting hours. We learned how to wash his hair in bed, how to change his position, how to avoid bedsores. It was draining, but not as miserable as it sounds. A multi-tasker, my mum balanced work and caring; I studied for the exams I never took while helping her with his exercises, holding up flash cards to see if he could say them or blink recognition, reading the paper aloud and talking animatedly to keep his attention ("Never cry in front of him," they said). Some days were good, happy; it was hard not hearing his voice, but we knew he was still there. Other days, when an infection took hold or a bad set of blood results came, not so good.

My dad was 67 when he died. I made it to the hospital in time to say goodbye. I remember being startled by the strength in his hand as he squeezed with his last breaths.

Locked-in syndrome isn't classified as a disease, so there are no precise statistics on the number of people suffering from it. It's also hard to identify, and to know the extent of it. All too often, locked-in syndrome remains undiagnosed, patients written off as lost causes when they are all the while aware of their condition, just unable to say so.

There have been a few miraculous recoveries, the occasional story making the news because of someone who defied the odds and broke out from being locked in. One of the most recent is Graham Miles, 66, from Surrey, who had a stroke and was paralysed, also able to communicate only by blinking. Miles can now walk, talk and has even taken up motor racing as a hobby. He puts his recovery down to willpower.

Others are less fortunate. It was in February that I first saw Tony Nicklinson on television, promoting his legal campaign. Tony had been a strong rugby player who travelled the world as an engineer. When I saw him on television, something about the way he sat in his wheelchair reminded me of my dad.

It wasn't just Tony who caught my attention. His daughters, Lauren and Beth, were on screen too. Both in their early twenties, they talked about how the man they knew when they were growing up was no longer there, because the stroke had taken him away. Here were two young women with whom I had something in common: daughters who knew what it felt like to see your father like that. That connection, or the hope of one, compelled me to get in touch.

Weeks later, I arrive at the Nicklinson's family home in Wiltshire, to spend the afternoon with Lauren, 23, and Beth, 22. I am painfully conscious that while the three of us have seen our dads suffer, my experience has gone further: my dad is no longer alive, as Tony is, just down the corridor.

"Everything changed the day dad had his stroke," says Lauren, who was 18 and doing her A-levels when it happened (Beth, 16, was taking her GCSEs). The Nicklinsons lived in the United Arab Emirates, at the time, and Tony had just left on a business trip to Athens when a colleague phoned to break the news. "I remember mum shut the door while she was on the phone, and she'd never do that unless there was something wrong. Then she told me that dad had a stroke. I remember feeling really scared. That night I slept with the door open."

I tell Lauren I know how she felt. I would sleep with the lights on. We are quietly surprised by small similarities: that we were all doing our exams when our dads got ill, that our dads had similar heart problems pre-stroke, that we discovered the blinks meant something by accident, that Lauren flew to Athens with just one change of clothes, just as I did when I flew back to Birmingham from Paris.

For Lauren, Beth and me they are small things which we have never shared with anyone outside our families. There are emotional similarities too; the desperate desire to reach out and save our dads from the indignity stroke brings, the guilt of moving on with our lives, the constant worrying about our mothers. We talk calmly, without tears but sad recognition for what it is we have lost.

Lauren tells me it hits her every now and then. "I went to a friend's wedding and it got to me that my dad will never give me away, never give me a speech. It's the same for Beth. We will never have that. I can only imagine these things now."

Lauren and Beth talk about their dad in the past tense. Even though he's still in the present, I understand why. "I'd rather think of him as then, not now," says Lauren. "If – or when he goes – it doesn't mean we won't grieve again, but when he had the stroke, we lost dad as a person."

Later on the train, I'm exhausted. It's not every day that you relive such intense memories. The aftermath of a stroke is sometimes so extreme that it can't be talked about casually, and sometimes that means it's not talked about at all. As Beth put it: "I don't go telling everyone I meet about what's happened to my dad."

For a long time, I promised myself I would never write about this experience, anxious about sharing something so private. Finding Lauren and Beth, with whom I can share it as equals, changed my mind. "I don't really know anyone else who's been through this," says Lauren when we say goodbye. "Other than mum and Beth, you're the only person."