In the winter of 1876, 15-year-old Louise Augustine Gleizes, a patient at the sprawling Salpêtrière women's hospital in Paris, had 154 hysterical fits in one day. She heard voices; she saw swarms of black, demonic rats; she felt an intense pain in her right ovary; and then she lost consciousness, her body convulsing in a series of violent seizures.

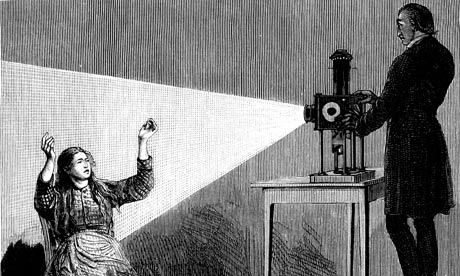

Yet this was not just a private problem. Each of Augustine's attacks were carefully monitored by her doctor, Jean-Martin Charcot, and his team. She was wheeled out to demonstrate her symptoms to a class of students, and along with other women patients, was photographed and hypnotised to exhibit the various stages of hysteria to packed-out public lectures – becoming, in the process, a celebrity in France and beyond.

Now the teenager's hysteria – along with fellow Salpêtrière patients Blanche Wittman and Geneviève Legrand – is the subject of Medical Muses: Hysteria in Nineteenth-Century Paris, a fascinating and beautifully written book by Asti Hustvedt. Originally the term "hysteria", widely attributed to Hippocrates, was used to describe a female disorder caused by a "wandering womb"– something now disdained as a misogynistic anachronism. Yet Hustvedt controversially argues that certain aspects of hysteria are still with us today.

Hustvedt, a French scholar, and sister of novelist Siri Hustvedt, has long been fascinated by hysteria and the Salpêtrière. "It was haunting me; I kept thinking, what does [hysteria] mean?" Yet Hustvedt's own preconceptions about the illness, and Charcot's treatment of his patients, also changed. She started out suspicious of his theatrical lectures in which the hypnotised hysterics were compelled to perform various degrading tasks, from stamping on imaginary snakes to kissing the hospital chaplain.

"There's a lot that we can, and we should, criticise Charcot for. These women were undoubtedly turned into medical specimens to serve his needs," she points out. "But at the same time, he did take hysteria seriously. He insisted that it was real, not imaginary or faked."

This serious analysis of symptoms whose origins can't be medically determined is not, she points out, always the approach taken by doctors and patients today. "If you are diagnosed with something whose origin remains murky – a syndrome – people experience it as something pejorative, or that they don't have a legitimate disease."

She also believes that Charcot's definition of hysteria as an almost exclusively female complaint – one produced by the strange, unknowable female body – continues to dog today's medicine. "In many ways we live in a culture that's far less sexist than Charcot's was," says Hustvedt, "but when it comes to the idea that the female body is, say, more vulnerable to hormones than the male body – that absolutely continues. As does the idea that anything connected to the entirely natural, biological female reproductive system – pregnancy, childbirth, menstruation, menopause ‑ is a medical issue."

Crucially, Hustvedt argues that it's no use asking retrospectively, now that the diagnosis of hysteria has disappeared, which contemporary disease Charcot's patients might have had. Hysteria, even if its causes remained mysterious, was, for Charcot and his patients, a real and recognised medical condition, some of whose frequently reported symptoms – such as sporadic limb paralysis – occur rarely today, if at all.

"All illness," she says, "is experienced in a specific time and place, and it is classified differently depending on what culture you're from. Significantly, they [the hysterical women] would probably not exhibit the same symptoms today."

But some of the facets of what was once termed hysteria, do, she says, still exist: in the many neurological complaints that still go undiagnosed; in eating disorders (some of Charcot's hysterics refused food); in the increasingly widespread diagnosis of depression (Augustine, Blanche and Geneviève all led extremely troubled and traumatic lives: towards the end of his life, Charcot was approaching a psychosomatic explanation for their symptoms); in self-mutilation, multiple personality disorder and chronic fatigue syndrome; and even in the sudden outbreak of rashes reported by schoolgirls across America in the wake of 9/11.

"There's been a lot of talk about how hysteria has disappeared," Hustvedt says. "In some ways that's accurate – it's no longer considered a medical entity or diagnosis. And at the same time, of course, it hasn't disappeared. People continue to write about it, people continue to talk about it; it's been broken up and reclassified into other, separate disorders. It's just that the names have shifted."