There is no etiquette for the way surgeons gain experience – the unfair truth is that the pushy ones do the most operations. But I'll never forget the time this backfired on a colleague who had a list of appendicectomies under his belt before I had done my first.

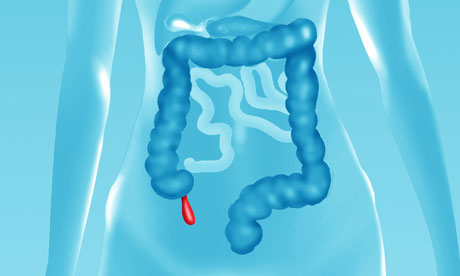

Often given the prefix "vermiform" because of its worm-like appearance, the appendix is a finger-like protrusion from a part of the bowel called the caecum. It varies in length between two and 20cm and nobody really knows what it is for. Darwin thought that the appendix might have been used for digesting leaves, back when we were primates but, more recently, it has been speculated that this little extension of the gut may harbour special, protective bacteria.

What we do know is that when the appendix becomes blocked (usually by faeces) it can become inflamed, causing the painful condition known as appendicitis. Undiagnosed, an inflamed appendix may rupture, causing pus and bowel contents to leak into the peritoneum, the thin fibrous sac containing all the abdominal organs. This condition, known as peritonitis, can be fatal.

Although it baffles patients – who often equate abdominal pain with appendicitis – it's a complaint that is notoriously difficult to diagnose. Medical text-books describe classic features of malaise and tenderness in a specific area of the abdomen known as McBurney's point but, in truth, the clinical presentation is often vague, and the list of other complaints which can cause belly-ache is long. In some parts of the US, CT scans are routinely performed to avoid unnecessary surgery on healthy appendices, otherwise known as "white worms". In this country, the decision to remove an appendix remains a judgment call.

My first appendicectomy, when it finally arrived, was handed to me on a plate – the young male patient was a textbook case. His pain was in exactly the right place and had increased over two days. As I walked alongside his bed into the operating theatre, I couldn't help asking him why he hadn't come in sooner. "Oh, I did," he replied. "But the male doctor I met yesterday seemed so excited about cutting me open that I got scared and went straight home again."