By eight o'clock on the evening before the wedding, the last jostlings in the table plan had ended and the numbers joining to dance after dinner had somehow been held to the level permitted.

I had seen the dress, hanging in its exquisite folds like a beautiful ghost, safely arrived from designer Georgina Chapman in New York (an old friend and schoolmate of the couple). Guests had gathered from far and near.

The bride, Jane, staying with her parents until the ceremony, made a goodnight call to her future husband (and my son), Max. He had just got back to their flat after a hard day's work at his studio, when he picked up the phone. They chatted briefly. "I love you," he said. And then, nothing, apart from a faint choking sound.

Across town, I was in my room, sending a few emails and looking forward to the next day. As the mother of the bridegroom, I reckoned, my role would be mainly to enjoy myself. That illusion faded when my hostess, Polly, burst in and thrust a phone into my hands. "It's Jane," she said. "Max is in an ambulance ..." I grabbed the phone and heard Jane say that he was on his way to Hammersmith Hospital and could I get there?

I don't remember leaving the house, only somehow being in a taxi. It dawned that I had no cash on me so we stopped at an ATM. As I waited for the notes to clunk out of the machine, I was thinking that perhaps we would have to postpone the wedding. A flickering hope.

At A&E I was shown to a room where I expected to see Max lying on a bed, but found only an anguished Jane holding her father's hand, tears streaming down her face. No one spoke. "Where is he?", I asked in panic. "Is he alive?" I spun around to find a doctor standing quietly by the door. "His heart stopped beating," he said gently. "We could not revive him."

Later during that long night Jane and I sat up with Polly, talking and weeping by turns, groping for comprehension. At dawn I went to bed, but my eyes seemed to be jammed open, "on stalks", like a cartoon character.

"You couldn't write this," Jane said. And after almost a year, this the first time I have tried. The aftermath of Max's death was so confused, and the fact of it so incredible, that even when - on what should have been his wedding day - I stood in the bleak little viewing room at the mortuary looking at him stretched out with something that looked like Grandma's velvet curtains draped over him, I could not believe it.

On the edge of his generous hand lying outside the cover I noticed a streak of green paint: a last reminder that Max was an artist. It was him and not him; here he was and yet here he was utterly absent. His hair was thrown back from his face; a small plastic tube was clenched in his mouth. I did not stay long, but left Jane talking and talking to him in a loving stream of consciousness, that she would never forget him, that he had shown her how to live.

That afternoon, most of the wedding guests, summoned by email and texts, walked en masse up Primrose Hill. At the top, Sam, the best man, addressed us and I began to understand just how much Max had meant to his legion of friends. "He was the cement in all our lives," Sam said, and at the end of his oration we all shouted "Max!" at the sky.

That was the first time that I felt suffused by a strange backwash of warmth, seeing off - briefly - the chill that was settling in me. The rush came again at the funeral, when even more - hundreds more - of his friends came to say goodbye. I have felt it many times since: early in the morning in my garden, or when I am with friends he loved, and sometimes when I am feeling low. Max specialised in the bear-hug, and I guess this is the best he can do from Over There.

So much has been written about death that I hesitate to add my spoonful of experience. It is a leveller, a common denominator, we are automatically signed up for it at birth. And yet its capacity to shock, and hurt, and bereave never diminishes - especially when, according to our hubristic programme, it comes too soon. As deaths go, Max had a good one: he had not suffered, he wasn't tortured or murdered, not wiped out in an accident, nor by a roadside bomb. He was at the peak of happiness and hitting his stride as an artist.

But the "good" aspects made his loss harder to take for those left behind, simply because he was young and seemed so fit and well. We were repeatedly told - by the coroner, the heart specialist's autopsy - that there had been nothing wrong with him. His heart was healthy, nothing toxic in his system, he was in good shape. At the inquest, the verdict recorded was simply "natural causes."

But there was a specific cause, and a stealthy one. He died of Sads - Sudden Arrhythmic Death Syndrome (sometimes called Sudden Adult Death Syndrome), an umbrella term for around a dozen conditions that kill at least 600 people under 35 a year in the UK. These deaths, linked to anomalies in electrical workings of the heart, have been compared to cot deaths in infancy. They have a special poignancy because there are few prior symptoms and the victims appear, like Max, to be in prime health.

Athletes on the sports field, a young girl thrilled by her first kiss, a teenager collapsing on to his birthday cake, a girl on her morning jog, somebody's son at the wheel, waiting for the lights to change - these are among the long roll of stories in the archives of Cry (Cardiac Risk in the Young). This charity works to raise awareness of Sads and helps to fund important research and a screening programme for under-35s.

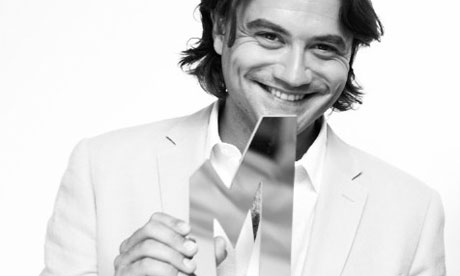

Max's family and friends miss his presence every day - his smile, his warmth and humour. However, as an artist, he left his work behind. Next week, just ahead of the first anniversary of his death, some of his pictures and prints will be exhibited in London. It will be a celebration of his life and work, but also, it is hoped, will raise money for Cry, and their campaign to save others from his fate.

• Max Lowry 1976-2010: A Retrospective. Mall Galleries, The Mall (near Admiralty Arch), London SW1, 12-18 September.

• Find out more about the Cry (Cardiac Risk in the Young) charity