Clearing some space from an old work email account recently, I found a message from my father, who died several years ago. It was a mundane note – a handwritten equivalent would have been thrown away. As I was remembering my old dad, I posted something about him on Twitter. This was reposted by a couple of others and spotted by a colleague of his, who took a moment to exchange a brief, 140-character memory with me.

This encounter highlights two key things about memory in the digital age. First, that more and more ephemera seems to be kept online – accidentally or otherwise. Second, that memories are becoming increasingly public – social, even.

The web has become an accessible – and often very public – repository for our lives: a place to store memories, to be reminded, and to find other people's memories too. For many people, this shared experience raises questions about the nature of memory. Remembering is often a deeply personal event – do we want to experience it collectively?

Last summer, there was a spate of "Google makes you stupid" headlines. Search engines, we were told, remember for us and, as a consequence, we are forgetting to remember for ourselves. Of course, things are rarely as simple as a headline. The research behind these stories, published in the journal Science, found that when people knew information would be stored on a computer, they were less likely to remember it (although they were better at remembering where this information was stored).

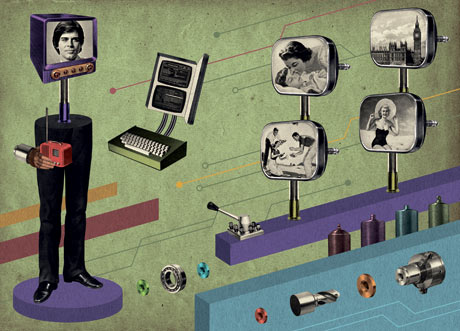

The research also pointed out that humans have long drawn on the power of "transactive memory". In other words, memory has long been stored outside of our own individual bodies, it's just that, increasingly, we are storing it behind small screens rather than on shelves. Before the silicon chip was invented, pen and paper, the printing press and the camera all helped store information for us, ephemerally or for posterity.

Memory has always been a social activity (think of remembrance days, statues or plaques) and our appetite for collective nostalgia is undiminished. The leaking of personal pasts didn't start with Facebook either. Embarrassing university photos of politicians are nothing new.

Some might feel constrained by the way in which digital technologies invite us to share memories. The "folksonomies" of online personal archives – collectively created taxonomies based on tagged items such as blogposts, photos or links – may connect us to a host of interested and interesting unknown people, but they ask us to be readable to others too. Such tags invite us to concentrate on what we share, not what makes us unique. But a collective memory can be incredibly useful – liberating, even. It connects and reconnects us to things we need or want and would otherwise be without.

Perhaps as we get more used to digitised memories, we'll become a little more open and honest about our own complex (and sometimes embarrassing) personal histories. After all, memories aren't just about recalling singular facts, but making connections within a complex network. Why not use technology to help extend and enrich this network?

• Alice Bell is a science communication lecturer at Imperial College London