A new generation of doctors will be put off from becoming involved in abortion services by high-profile protest campaigns and a political "witch-hunt", providers fear.

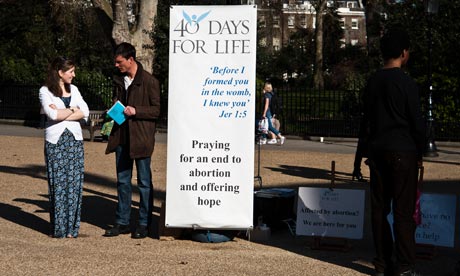

The current climate is already causing anxiety among doctors who are concerned that their practice will be called into question, the British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS) said, as activists behind a new campaign to demonstrate outside abortion clinics were joined at one protest in London by a Catholic bishop.

The warning comes as the BPAS and pro-choice campaigners say they feel "under siege" after the government ordered an unannounced inspection of more than 250 clinics in England, claiming as many as a fifth were pre-signing consent forms for terminations. The inspections by officials from the Care Quality Commission (CQC) were said to have found evidence of blank forms being signed in anticipation of women seeking a termination. Although doctors do not have to see the woman in person, they must certify that they are aware of her circumstances and why she wants to go ahead with the procedure.

A spokesperson for the BPAS said: "Abortion is a vital yet stigmatised area of women's healthcare which few doctors train in. The current politicisation of abortion provision is likely to make it even harder to recruit a future generation of abortion doctors who are prepared to provide the care that a third of women will need in the course of their lifetimes."

Dr Paula Franklin, medical director of Marie Stopes, which like the BPAS has contracts to provide terminations on the NHS, said she was concerned that the heightened scrutiny was having an effect on "existing clinics and on doctors and nurses who come every day to the centres, many of whom have to navigate through sometimes angry – sometimes not – protesters. That is difficult for them.It isn't easy to find doctors who will work in termination services. For some time now, relatively few of them have chosen to go into terminations. It is a problem."

On Wednesday, the Guardian published a letter from a group of senior clinicians and researchers who said they were "deeply concerned" about the way the public discussion on abortion is proceeding and about how the service will manage to carry on.

One of its signatories, Dr Kate Guthrie, clinical director with Hull and East Riding Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Partnership, said she had concerns about the impact that increased media and political attention could have on students and younger doctors.

"Of course, there is a lot of stigma around abortion, both having them and to a much lesser extent, even doing them. But from the feedback that I have had, I really do think that the question has to be asked: what impact is this increasingly negative politicisation going to have on future providers of abortion care? Is it going to put doctors and nurses off becoming involved in this work?

"Anyone thinking of becoming involved in abortion will be aware of the recent, very intense scrutiny of services, and I hope will not be put off by uncertainty in interpretation of the law and the thought of Care Quality Commission swoops.

However, another signatory of Wednesday's letter to the Guardian said he believed that the current climate was making things more difficult in the not-for-profit sector, though not for those working in the NHS, where involvement in termination provision was seen as "quite a positive thing".

"The RCOG [Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists] has a series of special skills that they expect senior trainees to undertake before they get signed off to be fully accredited specialists and consultants, and they provide an option of a pregnancy termination module," said Dr Malcolm Griffiths, a consultant and clinical director in obstetrics and gynaecology at Luton and Dunstable hospital.

"The difficulty is with later surgical terminations," said Griffiths.

"Most people in the NHS who do terminations limit themselves to 12 or 14 weeks. Increasingly more and more of those are done medically. Once you get beyond 14 weeks then it is a very small number of people who have the skills to do the later surgical terminations.

"It's probably not a dozen people in the country who are doing the ones around 20 weeks and beyond."

The question of how to step into the shoes of the older generation of abortion practitioners weighs on the minds of future doctors like Matteo De Martino, a fifth-year student at a northern medical school.

"Someone referred to it as the greying of current providers," says De Martino, who is in the process of setting up Medical Students for Abortion Care, which will aim to encourage the involvement of medical students in the debate about abortion and campaign for more abortion-related training in the medical school curriculum.

"Without them, we lose not just technical skill but also that pool of knowledge that has experience of, and treated the potentially fatal effects of, women being forced into backstreet abortion clinics due to its illegality."

Professor Wendy Savage, the country's first female consultant gynaecologist and long-time campaigner for women's healthcare rights, said that few doctors would now see late abortions, since most are now being performed in the private charitable sector.

Few doctors are trained to carry out late terminations, yet the small minority of women who come for them (91% are carried out under 13 weeks) are in the greatest distress. "Our experience is that women who do come for late terminations are often among the most vulnerable, whose lives and domestic situations are the most difficult," she said. They included women who have been raped, cases of incest and vulnerable women with difficult relationships that can include violence.