It was the flying frankfurter that did it. A supporter of Crystal Palace Football Club, probably intoxicated by a few pints at half time and his team's magnificent victory by four goals to three, decided to toss his half-eaten hot-dog into the Millwall supporters' enclosure.

Although there had been the usual animosity between these deadly rivals, it felt as though this was the spark that ignited some serious fighting in our area of the stadium. The brawling would encompass everyone within about five rows, even those of us sitting in an area set aside for disabled supporters.

But while there have been multiple studies of soccer violence, I have yet to come across anything that featured a severely disabled child, trapped in a wheelchair, yet encouraging his side to fight their opponents. It sounds absurd but that's precisely what happened on a winter's day in October 1989. And it involved my brother, Tommy.

"Come on Palace, Millwall are wankers," my brother shouted, even as I stood over him to shield his head and body from the ensuing ruckus. He even joined in singing another well-known Palace chant: "Fuck off Millwall, south London is ours." He wanted his team to win the football and their fans to win the fight. Most of all he wanted to be part of it. And for a moment, notwithstanding all of his physical limitations, he was.

Tommy was born with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), the most common fatal genetic disorder to affect children around the world. Children with DMD are unable to produce dystrophin – a protein absolutely essential for muscle strength and function. As a result, every skeletal muscle in the body deteriorates over time and the disease is 100% fatal. That's what makes so many of these children so remarkable. And if a death sentence is enough to undermine even the toughest of people, the process of decline is crushing to watch.

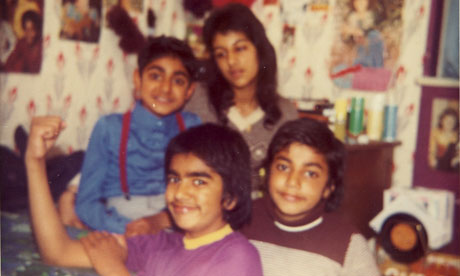

Although Tommy was two years older, I recall the growing realisation – just after my fifth birthday – that he wasn't as quick at racing and rarely put up a fight for toys. By then he was already attending a special school, being collected by a local authority bus that carried Tommy and his fellow pupils, who had everything from cerebral palsy to Down's syndrome.

It was one of the bus drivers, a tall Jamaican gentleman, who introduced Tommy to Crystal Palace. He could tell that Tommy was interested in talking, so would position his wheelchair close to the driver's seat and they would chat about football. As a result, from the age of nine, Tommy was Palace-mad.

It was also at that time that his legs began to give way.

We would visit a neurologist at the Atkinson Morley Hospital in Wimbledon for regular consultations. As with Mr Atkinson Morley himself, a well-to-do landowner who opened the hospital in 1869 with a donation of £100,000, there was kindness and compassion – but no possibility of a cure.

But something else was taking place in Tommy's life. His obsession with his beloved football team was helping in a way that the doctors could not understand. It was extending it. According to the neurologist, who would normally ignore anecdotal evidence, there appeared to be a direct relationship between Tommy's engagement with broader society and the longevity of his life.

But this came at a price. My mother's life was spent entirely in caring for him; turning him over at the dead of night; producing food that he could swallow; all the things that parents of children with DMD must give, every second of their lives.

For the siblings of such children, there is a little discomfort, too: a sense of guilt that I was not born with the condition; that I could play sport; that I could travel independently; that I would outlive him.

In practical terms, often on match days, my responsibility would be to wheel him into the bathroom and help him do things that most of us do in private. It must have been humiliating for him; but from my perspective he was the epitome of heroism. Because, even though he could not feed himself, he was fighting for his life.

In January 1991, almost two years after the Crystal Palace/Millwall fracas, Tommy's heart and lungs had reached total exhaustion. He had hammered them for just over 29 years and outlasted every one of his closest DMD peers. (At the time, the vast majority were unlikely to make it beyond their 20th birthday, although medical care has since improved with many now living into their 20s and 30s.) Tommy had fought the disease with everything that he had but Duchenne muscular dystrophy finally got the better of him.

The funeral service, at our church in south London, was difficult for all of us. But just before the service began, two of Tommy's favourite Crystal Palace players – Tony Finnigan and Ian Wright – came in through the doors. I had been to the same school as Tony and we had been friends for years. Ian, by now, had also become a friend.

As I accepted their condolences, Ian produced a pair of boots – still covered in grass and mud – and handed them to me. His eyes blinking through tears, he said: "These are the boots that I was wearing when I scored two goals in the FA Cup final last year. Put them in Tommy's coffin because he's gonna need them."

I'm sure he's putting them to good use.

Martin Bashir is a patron of Actionduchenne.org, which promotes awareness, raises funds and offers support for those affected by muscular dystrophy.