A new type of fertility treatment that could prevent a woman from passing a rare class of genetic disease to her children should be approved by the government, according to the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, provided research shows the techniques to be safe and effective.

The council also said that the commonly used shorthand for the techniques used in media reports and elsewhere, "three-parent embryos" – because the resulting children contain genetic material from three people – was misleading and should be avoided.

Mitochondria are tiny structures inside the body's cells that convert the carbohydrates and fats we eat into useful energy. An adult cell might contain a few hundred to several thousand depending on its functions.

They have their own set of genes, distinct from the genes in the nucleus If these are somehow defective, they can affect the way a cell is able to use energy, causing a range of disorders including malfunctions of the heart, kidneys and liver or leading to stroke, dementia, blindness and deafness.

"It's been estimated that 1 in 6,500 children develops a serious form of mitochondrial disease, that's about 2,000 children affected in the UK," said professor Frances Flinter, a clinical geneticist at King's College, London, and a member of the Nuffield Council working party. "There are currently no cures for mitochondrial disorders because the mutations that cause them are present in every cell of the body and cannot be fixed."

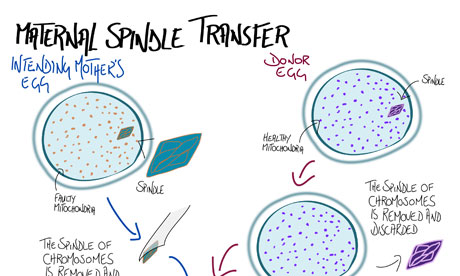

In the past decade, however, scientists have developed methods that could prevent the transmission of mitochondrial DNA mutations from mother to child. The nucleus of an egg from a woman with defective mitochondrial DNA can be placed into the centre of a healthy, donated egg that has had its own nucleus removed. This composite egg, which has all the potential mother's chromosomes but the donor's healthy mitochondria, can then be fertilised by the father's sperm.

Before it can be legally used by clinicians in the UK, however, the techniques would have to be approved by a vote in parliament.

The Nuffield Council on Bioethics brought together a working party of scientists, ethicists, doctors and lawyers eight months ago to consider the ethical issues of the new technique. Its report, published on Tuesday, concluded that it would be ethical for families to use mitochondrial donation provided future studies showed it to be safe and adequate for clinical use.

The report said families undergoing treatment should be offered advice from appropriately trained counsellors and that the technique should only be offered as part of a clinical trial at specialist centres.

The working party also considered the rights and responsibilities of the egg donor. "Mitochondrial donation does not indicate, biologically or legally, any notion of the child having a third parent or second mother," said Geoff Watts, who chaired the working party. "We find it disappointing that these techniques continue to be referred to in media reports and elsewhere in these terms. A lot of people in the business are not happy with this constant reference to third-parent techniques. It is a distraction from more important ethical issues."

Mitochondria contain 37 genes, as opposed to 25,000 or so genes in the nucleus of normal body cells. This means that around 0.1% of the DNA of a child born through this technique would come from the donor and 99.9% would come from the real parents. "Mitochondrial genes alone create no identifiable or distinct link between a child and the donor," said Watts.

Dr Catherine Elliott, head of clinical research support and ethics at the Medical Research Council, said the Nuffield report presented "a thoughtful analysis of the ethical issues raised by ongoing research into incurable mitochondrial disorders".

Patient groups also welcomed the conclusions. Dr Marita Pohlschmidt, director of research at the Muscular Dystrophy Campaign, said she hoped the Nuffield report would answer questions for the public. "We urge the government to recognise the human cost of delaying the further development of this treatment, and to act swiftly to allow it to progress."

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority is consulting on the mitochondrial transfer technique ahead of a final decision on whether parliament should approve it next year.