From the developing world to the UK, the statistics are clear: teenagers who miss out on education are more likely to have sex younger, less likely to use contraception, and more likely to get pregnant.

A survey carried out as part of the 2001 census in the UK showed that fewer than half of teenage mothers were going to school when they got pregnant. About a quarter of boys and a third of girls who left school at 16 with no qualifications did not use contraception when they first had sex, compared to only 6% of boys and 8% girls who stayed on till 17 or over and got qualifications.

A 2008 study of 38 mostly poor, developing countries found that 15- to 17-year-old girls who were enrolled in school were less likely to have had sex than girls who weren't in education. Nearly 13 million adolescent girls give birth each year in developing countries; a girl growing up in Chad is more likely to die in childbirth than she is to attend secondary school, according to the IPPF. But if a girl in the developing world receives seven or more years of education, on average she marries four years later and has 2.2 fewer children.

Leaving school also affects chances of picking up STIs: studies of HIV in Africa and Latin America have found that education lowers women's risk of infection and the prevalance of risky behaviour.

Without the natural hub for young people that is created by school to rely on, how do sexual health professionals ensure the most vulnerable teenagers get much needed education and access to services?

In Bolivia, where 20% of pregnancies are in the 15- to 19-year-old age group, peer educators are at the heart of a successful programme run by sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services provider CIES targeting children and teenagers living on the streets. More than 2,000 youth volunteers aged between 10 and 18 who come from a similar background, or have grown up in other difficult circumstances, give talks, hand out condoms and encourage young people to access services — while, crucially, gaining their trust. Since the "Tu Decides" (You Decide) programme began 20 years ago, the number of young people becoming leaders, normally after using one of CIES' services themselves, has increased by 25% each year.

CIES runs 14 health centres and three mobile facilities serving rural areas. Each centre has as dedicated "youth corner", designed and run by young people to attract others, and offering free internet access, books and games, as well as opportunities to take part in sports, music, and job skills training. Services are free for the poorest young people and doctors are trained in a "bio-psycho-socio-cultural" approach that sees them consider and discuss all aspects of a patient's life, not just the problem they're seeking treatment for.

"They have a lot of issues and most of the time it's not only health problems," says Martin Gutierrez, CIES' communications manager. "They need to talk, they need to have human contact. A key part in all this is our doctors creating a bond with them."

Drug use is common among clients who live on the streets, as is involvement in sex work and crime. Many have suffered sexual violence.

"When they come here they find not only doctors who can talk with them but also other people who are just like them," Gutierrez says. In 2011 CIES worked with 12,000 young vulnerable people, that number increases by 10% every year.

An important part of the education work in the clinics is explaining to young people what their rights are. It's not unusual, for instance, for other medical professionals or pharmacists to refuse to give out contraception, even when teenagers want to pay for it, telling them they're too young to have sex. CIES lets them know they have the right to demand those services.

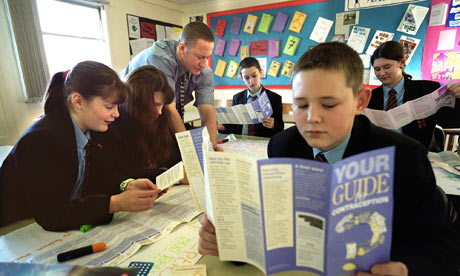

In the UK, creating bonds with the young people being educated is no less important. Around half of the teenagers Jennifer Lawson works with as part of the FPA's Sexability project in Glasgow are out of mainstream education, and it helps when delivering sessions through alternative provision that she's not a teacher, she says.

For pupils who often have short attention spans and behavioural problems, her approach is as hands-on and discussion-based as possible – chatting works much better in a setting where worksheets and presentations from the front would be far too much like English or maths. Instead she gets pupils thinking about issues like the effect of alcohol by asking them to put condoms on a fake penis while wearing "beer goggles" — glasses used in anti drink-driving campaigns to show how being drunk distorts vision.

Groups also take turns to pick different types of contraception out of a box Lawson has covered in fake fur and then discuss their use. The innuendo-laden "furry box" is an excellent ice-breaker and keeps pupils engaged, she says. "It sounds daft but it's a great hit. It means they get to physically touch stuff like coils, rings and implants, rather than just looking at pictures."

To succeed with these kinds of groups educators need to make clear to young people that they are not there to criticise or judge them, says Helen Corteen, the centre director at Brook in Wirral, which works closely with the local youth offending service and offers courses that include work on self esteem and risky behaviour such as recording pornographic images on mobile phones.

"It's about starting where they are, rather than saying 'you've been sent on this course because you've done something wrong and we're going to fix it'," Corteen says.

And getting sex education in this kind of setting means it's sometimes actually much wider ranging, according to Lawson: "We do a lot of work on values. A lot of mainstream schools won't let you go into that much detail." Despite the occasional problem with behaviour, she finds these young people tend to be more willing than others to get talking about sex — and really engage with the sessions. "They'll just tell you what they think," she says. "They're happy to have a laugh, which is great when you're tackling this sort of thing.

"They love telling you their opinion, because a lot of the time they're not asked. They're really keen to get their voices heard."