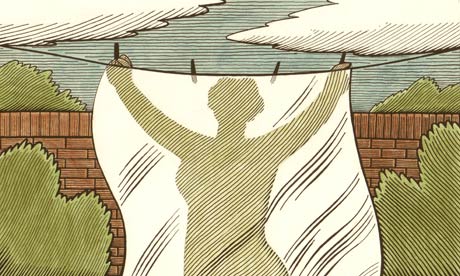

As a child I was riveted by other people's mothers: their air of being possessed – perhaps even imprisoned – by their lives constituted a kind of two-way mirror through which I could see them without, it seemed, being seen myself. I lacked this facility with my own mother: not only could I not truly see her, or see her whole, but she seemed to know things about me that I was not aware of having made public. At home the struggle to establish and defend the boundary of self was interior, whereas with other people's mothers everything was accomplished by a mutual reading of surfaces which, if occasionally awkward, offered much more in the way of entertainment. One could lie, for instance, without appearing to be found out; but most of all one could view in safety the maternal persona itself, which more than any other was exposed by the forms it took, so that it seemed there was nothing you couldn't find out about someone else's mother simply by looking. She expressed herself in everything, from the food on the table to the washing on the line, was intimately revealed in every room of the house, a creature entirely given over to outward impressions both sensory and actual – a person, in fact, with no privacy. While staying at a schoolfriend's house I was taken as a matter of course to view the marital bed, and was solemnly shown, as well as the items on her mother's dressing table and the contents of her underwear drawer, a tennis ball attached to a length of rope which lay beneath her mother's pillow. She wore it, it was explained to me, around her neck at night, in order to prevent her from disturbing her husband by lying on her back and snoring.

If there are two distinct kinds of mother – other people's and one's own – then this is a distinction reflected at the core of human nature, between ourselves as objective and subjective beings. Objectivity is the goal of civilisation, an aspiration rooted in the struggle to be objective about oneself. Psychoanalysis might be seen as the attempt to abridge this process, but for most people it is by the slow and iterative business of living that they approach a more dispassionate standpoint. A woman stuck at home with small children might for the first time be able to see that fierce deity, her mother, as a woman stuck at home with small children; but she is still some way from transposing a difficult mother into something that doesn't define or threaten the parameters of her own conduct. One can be a difficult mother and have a difficult mother, both at the same time: certain artists have the gift of clear sightedness in that particular hall of mirrors, but generally it's a question of trying not to repeat what was done to you while never quite knowing what it is you're meant to be doing.

Retrospect is no guide, despite the soft-psychoanalytic suggestion that one can become a better person by understanding the ways in which one was wronged. And as Terri Apter demonstrates in Difficult Mothers, the impulse to attain greater objectivity about formative experience can simply result in more entrenched subjectivity. In her introduction, Apter mentions a female friend and colleague who warned her against writing her book for precisely this reason. Mothers are blamed for everything, the friend says, and thus their perspective is dispensed with. Once a difficult mother becomes "difficult mothers" – once the particular problem is permitted to become generic – the two-way mirror is shattered and the battle for a more objective glimpse of our genesis is lost.

"It comes without warning. I turn my gaze out my office window, anticipating one of those exquisitely private moments when memories and long-term musings sweep away the deliberations of the day. Instead, I suddenly chill to memories of my mother's angry breath and feel its rhythm in my own heartbeat." These are Apter's opening lines: with their telling reliance on uncorroborated thought-scapes and physical symptoms, they demonstrate the reverse procedure of subjective "truth", whereby the personal does not become the universal but rather its opposite, forced to retreat to within its own strict boundary, the body.

Nonetheless, I left Difficult Mothers lying around the house, in case my children should be interested. It assigns mothers into categories – controlling, narcissistic, envious, unavailable – from which one feels somewhat forced to choose, though presumably as in the ice-cream parlour there's no law against having more than one kind at once. Afterwards one is invited to ask the question "Am I a difficult mother?", so perhaps it's best not to over-indulge. I found my thoughts straying to Oedipus, who was far from rehabilitated by such lines of enquiry. Indeed, it might be that in discovering one's parents to be mere humans, and one's sufferings, ambitions and darkest drives to have been generated by people not wicked but just hapless or hopeless – themselves the children of Larkin's fools in old style hats and coats – one loses something in the way of self-importance and belief and becomes, like Oedipus, someone of no fixed purpose or abode. The great Alice Miller took a hard line on such circular thinking: don't start feeling sorry for the grown-ups, she said. After Freud and Winnicott and Klein, she recognised that in the great mapping out of childhood reality there had to be a boundary somewhere.

Apter is one of many writers drawn to that new country, busily extracting and disseminating simplified versions of its precepts. She herself may not be ignorant, but she presumes ignorance in her readers, and is occasionally guilty of claiming that she has charted virgin psychoanalytic territory. "Instead of 'good' versus 'bad' mother," she writes as an instance, "I use the term 'good-enough' mother"; not exactly taking credit for Winnicott's famous phrase, but not attributing it to its author either. One might define a difficult mother as one who substitutes personal for actual truth, who interposes her own reality in a way that blocks or interferes with the child's view of "reality" itself. With her personalising of what were intended to be universal tools of self-knowledge, Apter oddly exhibits a version of such characteristics. In a writer such strategies are not exactly bad, but they're probably not good enough.

• Rachel Cusk's Aftermath is published by Faber.