On Dad's computer, on the desktop, there was a simple text file called Diary. In it, there were various things for him to remember: the times when friends and family were visiting, something about the dog. The last item in the list was for a dental appointment in January 2013. Appended to the entry, he had written, "If I'm still around."

When my father was diagnosed with a terminal brain tumour and given just a few months to live, many people told me that at least we would have the chance to talk and say goodbye. Friends told me to make sure I said what I wanted to before it was too late. As I had always had a warm and loving relationship with my father, I expected a desperately sad and poignant time, full of weighty conversations, paternal wisdom and meaningful moments in sunlit rooms.

But it wasn't quite like that. My father didn't talk much about dying and we didn't have any serious conversations about the meaning of it all. There was no Last Lecture or the near rapturous reckoning that Philip Gould found in his short film, Lessons from the Death Zone. Rather, Dad was reticent, nonchalant and somewhat detached. Much of this was due to his condition: his brain had been dulled, as he said; he knew what he wanted to say, but couldn't find the words. But it was also because he didn't see any point in talking about death.

I was drinking pink champagne – an early Valentine's celebration with my wife – when I found out he was dying. It was Dad who called, but he passed the phone over to my mother. It wasn't easy, she said, but they had some bad news. An inoperable brain tumour. My mother's voice cracked and I took a deep glug of champagne.

From then on, the words between us were difficult – so unlike how it had always been. I started with macho bravado, hoping to put him at ease: "Well, this is a bit shit, isn't it?" Something, a sigh, a nervous chuckle, perhaps.

"Well, to be honest," he said, "I'm not as down about it as you might think." Then, tears swallowed, shunted away, we sought refuge in the practical, the clinical details: was there anything that could be done? Was it inoperable? Then flights, train times, my home phone, which he wanted me to get fixed.

At home in Cornwall, Dad was dying the way he lived, with a quiet, understated enthusiasm. The banality of it all unnerved me. Shouldn't we be talking man-to-man about his life, his fears, his wishes for his grandchildren, instead of listening to the World at One and eating cheese sandwiches? After a few days of coffees, walks and cake, I thought, Dad, you don't have to be so stoic about this, show some fucking reaction, don't just sit there listening to University Challenge without even trying to get anything right.

Throughout the last weeks of his life, this need to have a meaningful father-son conversation became an obsession. I know why I snooped around on his desktop that day. I was looking for something, anything, that told me how he was feeling, about his illness, his life, his death.

One morning, with my wife and son still asleep, I could hear him padding around downstairs making my mother tea. I caught him on his way to the fridge and put my arms around him. I told him how sorry I was that this was happening to him and that he was a wonderful father. I didn't know whether he wanted to talk about such things, I said, but that I was always here for him if he did want to.

His reaction was muted, indecipherable. He took the milk out of the fridge and shuffled to the sink. I wasn't sure if it was embarrassment, discomfort or whether he was too upset to speak.

Later, when I sat upstairs, replaying the conversation in my head, I explained away his reticence as a function of his condition (a common side effect of brain tumours is emotional detachment). I imagined synapses flickering, his operating system sluggish, overloaded, struggling to compute. The reticence was not all him, though. It is a horrible thing to admit, but I found it difficult to talk to my father when he was dying. I felt awkward around him.

We struggled to make conversation, like two dullards on a first date. We made small talk, about how Brighton were doing in the Championship, my shin splints or the weather.

But sitting next to Dad's bed in the last three weeks of his life, the silence broken by the baroque rise-and-fall of his snores, I realised that my expectations of death – or specifically, of a father dying – had been skewed. All those HBO television families, flawed yet fundamentally decent, in which fathers told sons they loved them, and wept, and skeletons were uncovered and put to rest; then they wept again, their family cuddles resembling football huddles. In novels, people died differently.

This was nothing like that; there was no denouement, no emotional epiphany. Losing someone you love is so often reduced to a formulaic partitioning – of denial, loss, acceptance – as if grief were a series of tasks that could be divided into neat chunks and project-managed, as if pain were just a climbing wall to overcome on a team-building weekend.

The serious conversation I had sought so badly was just another notch, a box I thought should be ticked; a futile, vain notion that I might arrive at that horribly secular and soulless end-station of closure.

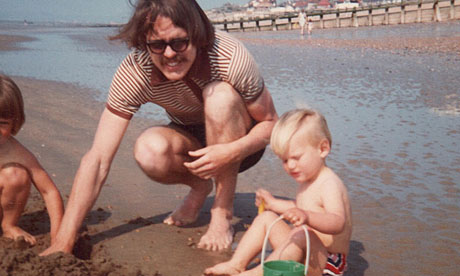

In the end, Dad died quietly, as he had lived, with little fuss. It was only when the chances of serious conversations were long gone, that I understood I had placed too much value in the spoken. The things that meant a lot – and have stayed with me since – were wordless: Dad sitting with my son, Tommy, on his lap, showing him his CD Walkman; the times, as I was holding Dad's slumping, naked body as we helped him off the commode, when he would wrap his arms around me and hold me tight; the moment once when we were squabbling – as families do at such times – and Dad groaned, a sound devoid of language but packed with meaning. Dad, ever the peacemaker, didn't want us to argue. Especially not now.

Three days before he died, I came back from a run along the cliffs and, dripping wet, went up to see Dad. I sat down on the chair next to the bed and held his hand and told him about the rain and the beach and how I'd expected the tide to be out, but in fact it was almost completely in. He was mouthing and whispering words, a husky, almost catatonic growl, as if he was speaking in tongues.

I felt he was trying to tell me something and that perhaps this might be my last chance to speak to him. So I told him once again how much I loved him. I bent down and kissed his cheek and greasy matted hair. I pulled him closer and dripped sweat over his face and told him what a fantastic father he was.

When he wasn't ill, if I had said such a thing, he would have said, "Ah, Lukey" and in just that short response there would be self-deprecation, a mild derisive scorn for a sentiment that he didn't think was necessarily true, gratitude, humility. This time his "ah" was little more than a groan, an abbreviation, an echo of a past life, yet one that in inflection and tone was so full of him. I held his hand for a little while longer and then left, holding back the tears until I got into the shower to wash the rain away.