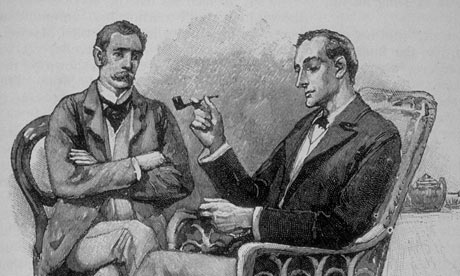

When she was little, Maria Konnikova's father read her Sherlock Holmes stories. She was captivated by "A Scandal in Bohemia", when Holmes asks Watson how many steps run up to their room and Watson is stumped. "You have not observed," tuts Holmes, annoyingly. "And yet you have seen … Now, I know there are seventeen steps, because I have both seen and observed."

That's true of all of us. We see, but we do not observe. Cognitive biases distort the way we think all the way along the line. We are victims of priming and stereotyping, confirmation bias and the conjunction fallacy, probabilistic incoherence, the default effect and goodness only knows what else.

If we wish to overcome these biases and emulate the great detective it's not enough just to shack up with a butch medical man, take a bunch of cocaine and learn the violin. We must recognise that our brain has two systems: System Holmes and System Watson. The former is mindful, attentive, self-questioning and rational. The latter is quick to action, prone to travel along familiar paths, and will tend to bungle when the chips are down.

We spend most of our time running System Watson but, says Konnikova, it's possible to train ourselves to run System Holmes – and if we get into the habit, eventually it will become second nature. "It won't be easy," as she often warns. But, as she also often promises, "our brains' very structure can change and develop … even into old age."

The recipe is clear. Here is a giant helping of Daniel Kahnemann, a tincture of Atul Gawande, a whiff of Nassim Taleb, a dollop of Jonah Lehrer, a salting of context-light neurosciency stuff ("it experiences tonic activity in what's now known as the DMN, the default mode network: the posterior cingulate cortex, the adjacent prenucleus, and the medial prefrontal cortex") and the whole assemblage served, Heston Blumenthal-style, in a deerstalker hat.

A good deal of Konnikova's advice, boiled down, is straightforward: pay mindful attention, think twice, question your own assumptions, be methodical, and if you're stuck on a problem take time out to let it percolate through your unconscious while you go for a stroll / do some knitting / chase the cat round the house with a Nerf gun. Be aware, above all, of your own fallibility.

What's most interesting in the book is how this stuff is backed up by scientific trials – and how extreme they show our cognitive distortions can be. I was delighted to be introduced to the ingeniously constructed Implicit Association Tests – which, in effect, show that you're much more racist and sexist than you think you are – and directed to implicit.harvard.edu, where you can take them yourself. And to hear how success at things can make us measurably worse at them is kind of wonderful.

Konnikova doesn't half flit and skim, though. She'll describe Darryl Bem's study apparently evidencing ESP, for instance – but it's to Google you'll need to head if you want to find out how and why it was exploded. Likewise, when she talks about "the Florida effect" or the "hard-easy effect" she does so with frustrating cursoriness. The former suggests that if you "prime" test subjects with words associated with old age (lonely, careful, Florida, helpless, knits and gullible will do it, apparently) they'll get scatty and start walking more slowly. The latter, even more startlingly, says that we're more likely to be overconfident when a task appears difficult than when it's easy. Even as you ask: "Really? Evidence?" she's on to the next thing.

Forgetting, too, that a prime pleasure in the reading of a Holmes adventure is the reveal, she frequently gives you the set-up without telling you what actually happens. Holmes curses himself, she says, for not realising that the newspaper is a vital clue in "The Adventure of the Stockbroker's Clerk". A clue to what? She doesn't say. A bloody fingerprint in "The Adventure of the Norwood Builder", she tells us, is to Holmes decisive evidence of the innocence of the accused. But how? She doesn't say. In The Sign of the Four, we hear Holmes's deduction that the villain came in through the hole in the roof. Which hole in the flaming roof?

Holmes is sometimes less consistent than Konnikova would have it, too. At one point, she discusses his indifference (why waste mental space storing the answer?) to the question of whether the earth circles the sun. At another, she mentions with approval that a case hinges on his happening to know about an obscure species of jellyfish. She attempts to square the circle with thoughts about curiosity, open-mindedness and the way you stock your "mental attic" to make sure that nothing that might come in handy is omitted – but, of course, the actual answer is that Holmes knows about the obscure jellyfish precisely because that case turns on it. If another case turned on Copernican theory, Holmes would have known about that too … because he's a made-up detective.

The conceit of this book requires us to treat Holmes as a real person rather than a literary artefact, and his creator as a penetrating psychologist with an intuitive grasp of the future discoveries of neuroscience. Konnikova gets a fair way with this, but in the final analysis it's a selling point rather than the structuring principle for a grown-up book. Holmes's job as a character is to embody the idea of a man with stupefying mental control: he is a collection of showbiz tricks rather than an actual case study. Superman comics don't have much to tell us about the physics of flight.

And as far as mindfulness and attention to detail goes, Holmes's creator was far from the paragon this reading requires him to be. The details of Watson's war wound and his marriages – even the location of his consulting rooms – famously shift around, the name of Holmes's housekeeper inexplicably changes at one point, and in one story a woman gets her own husband's first name wrong. Conan Doyle was writing pulp fiction, with consistency not his prime concern.

Plus, as Konnikova semi-sheepishly discusses in a final chapter called "We're Only Human", Conan Doyle was not just a fanatical spiritualist but also the guy who swallowed the Cottingley Fairies lock, stock and barrel. The points she makes in his defence, many of them fair, underline her argument that we are all conditioned by our environments and expectations. But if even the creator of Holmes can't stop System Watson from creeping in, what hope for the rest of us?

The question Konnikova's book promises to answer is: "What can Sherlock Holmes teach us about how our brains work?" The question it actually answers is: "How can I make a book about how our brains work into a book about Sherlock Holmes?" Here is a decent if sometimes repetitive meander though some interesting findings in cognitive and social psychology, gussied up as self-help and launched into what it hopes will be a market – to use the book's own term – "primed" by Benedict Cumberbatch.

• Sam Leith's You Talkin' to Me? is published by Profile.