As part of its sex education lessons, a west London primary school gave its year-six pupils the chance to ask any question they wanted anonymously.

The 10 and 11-year-olds' questions – with the boys posting into a box to be answered by a male teacher, while a female teacher answered girls' questions – revealed that rather than wanting to know about the biology of sex and reproduction, the children's main concerns were the changes to their bodies.

They wanted to know about where on their bodies hair would sprout – and how long it would grow. Girls wanted to know how wide their hips would grow, while boys wanted to know how much they would sweat.

One boy plaintively asked: "Does puberty ever end?"

Sex education in primary schools is an emotionally charged issue – although the term sex education itself is a bit of a misnomer.

As Simon Blake, chief executive of sexual health charity Brook says: "It is completely misleading to say that four-year-olds are being taught about sex."

In fact, some schools call the topic, covered in personal, social and health education, "growing up" or "our bodies".

Sex education is compulsory in schools, but lessons are often part of science classes and do not focus on relationships. Last week MPs launched a bid to make education about relationships mandatory too.

"The quality of SRE varies a lot between schools," says Lucy Emmerson, co-ordinator of the Sex Education Forum, a coalition of organisations that campaigns to improve sex and relationships education (SRE) for children and young people.

She adds: "In the best schools teachers regularly consult pupils about what they want to learn about and when. They have a planned curriculum with SRE beginning at the start of primary school and being built on year by year. This means that something topical can be picked up and the teacher can address it in another lesson.

"Asking children to write their questions privately and post them in an anonymous question box is a good way to get around embarrassment that children may feel to ask a question out loud."

The questions of the west London year-six class, says Blake, are typical for children of that age.

"By that age, you have learned the basics, that there are boys and girls, some people have blue eyes and some have brown eyes and you have started to see that things will change," he says. "There is a natural curiosity and wonder about the human body – children around 10 or 11 also want to know why farts smell or why our eyeballs don't pop out of our head when we sneeze.

"Year six is when children start thinking about what is going to happen. It is really critical that earlier in primary we get it right; if we don't, boys wonder if they are going to have periods."

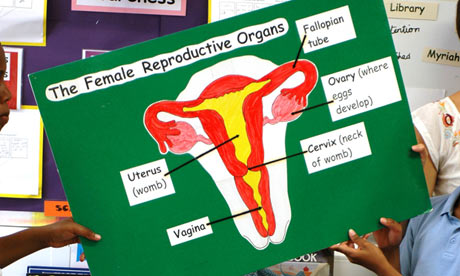

The questions children most want to ask will change as they get older, says Emmerson. Young children, aged between three and six, are interested in the differences between boys and girls, naming body parts, where babies come from, and friends and family.

"It is also vital that young children learn about which areas of the body are private and should not be touched and who they can talk to if they are worried," she says. "Adults have a responsibility to give this information to children … not just to wait for their questions."

Seven and eight-year-olds will have more questions about growing up and how their bodies will change, adds Emmerson. They also want to know about friendships and how to manage issues such as bullying.

Pupils reaching the end of primary school will have more detailed questions that will take in a range of issues – including love, different kinds of families, puberty, conception and how babies develop and are born – sometimes prompted by things they have read, seen on TV or the internet or heard from friends.

The Sex Education Forum has produced sets of questions to explore with children organised by age groups.

"In the worst schools, SRE may consist of one lesson about puberty in the summer term of the last year of primary school year. This is clearly a disgrace," says Emmerson.

"Some schools are held back by fear about how parents will react. Yet many parents assume that schools are covering these topics and are surprised and disappointed if they find out how little the school is doing and how late key topics such as puberty are taught."

Blake adds: "Many parents do feel embarrassed about discussing these issues with their children. Parents often assume schools do more than they do, and schools do less than they might because they are worried that parents don't want it – it is a double-edged sword."

Children want their parents to be their first sex educator, says Blake: "Primary school-age children trust their parents."

He and Emmerson agree that parents and teachers both have a role to play. The Sex Education Forum has put together some tips for parents.

Brook has also created a traffic light tool for professionals working with children and young people which helps identify, assess and respond appropriately to sexual behaviours.