For as long as spectators have wanted to crowd around men playing games, so have those who document sports boasted of how many women flock to service all those captive fans. Historians have claimed that along with athletes and the people who adored them, prostitutes, too, poured into ancient Greece for the Olympics, where they could earn a year's pay working the stands.

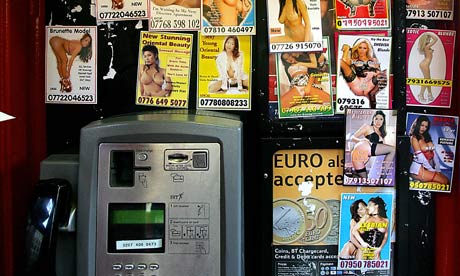

Now, the modern sex worker is believed to follow a similar migratory path, though considerably expanded by the reach of global tourism and mega-sports spectacles: the World Cup, the Grand Prix, the Super Bowl – all supposedly draw thousands of women offering paid sex.

It's an alluring fantasy, the kind of thing you could imagine in a dusty smut book, or serving as winky fodder for escort agencies and strip clubs in their seasonal marketing. The fantasy asks us to imagine the visiting packs of excitable men, engorged by victory or deflated by defeat. Who will celebrate with them? Who will soothe them? Worse, all that running and ball-chasing (or just watching it) is said to stoke a demand for sex so high that it would exhaust a city's native sex industry.

In headlines alternately titillating and cautionary, we were told that during the 2012 Olympics, London was to be "flooded" with prostitutes, and that for the 2013 Super Bowl in New Orleans, the city would host a "dark underworld" of illicit sex-for-sale. Like all fantasies, the "roving sporting sex workers" trope should be mostly harmless. It tells us about our culture's deeply-held myths and fears about sex work, but it can do little to spur any real concern for sex workers. In other words, it's an innocuous fantasy – until seized upon by those who find it threatening or politically useful.

Perhaps unintentionally taking a page from the sex industry itself, opponents of sex work capitalize on the roving-sporting-sex workers-fantasy for their causes. Anti-prostitution charities, called in by the media as experts, enjoy increased visibility. Similarly, law enforcement can stoke fear to garner public support for crackdowns on sex work – and too often, by extension, on those who perform it.

We saw this recently in London, where police raided brothels, arrested sex workers, and threatened them with further arrest if they returned to their neighborhoods – all part of their effort to "clean off the streets" for the 2012 Games. Contrary to claims that such crackdowns would focus on "the johns" and "demand", outreach workers reported that the police made it harder for them to provide sex workers with safer sex supplies, health information, and service referrals. Georgina Perry, service manager for Open Doors, an outreach service operating since 2003, writes that the fallout from Olympics-motivated crackdowns is ongoing:

"I'd say that we are currently picking up the pieces, and that it is going to take us a long time to restore sex worker faith in institutional support. Where once the relationship between sex worker services and clients was good, it is now broken. We are now viewed with suspicion as 'do-gooders or enforcers'.

"Where once sex workers may have felt it possible to report crimes against them to the police, there is now a dangerous and distrustful environment in London with crimes going unreported for fear of unwanted repercussions."

A similar pattern of pre-game publicity, followed by arrests, played out in New Orleans in the days before the Super Bowl. Anti-prostitution activists like Terra Koslowski warned the media, "we know that pimps show up from all over the country for what essentially is one big party." She was going to the Super Bowl, too – to put bars of soap printed with "Save Our Adolescents from Prostitution" in hotels, and a national hotline number into all their rooms.

Fox News had a camera crew follow a team of volunteers as they attempted to rescue "sex slaves" from streets and strip clubs. "Potential signs included hurried girls, struggling to make eye contact", the network explained. They snapped mobile phone photos of license plates they believed belonged to "johns", and recorded a group of women who appeared to be taking a cigarette break in front of a club. The report continued:

"While tourists may believe a stripper's smile is a sign she's choosing the lifestyle, the trained advocates and police investigators know it could be a trick."

With nearly any woman working in a club a potential target – or any woman on the street, hurrying home with her eyes down for whatever reason – it may be a minor miracle that the New Orleans police department has reported only eight arrests, and these with the considerable resources of the state police, the Department of Homeland Security, and the FBI. They also report making "rescues" – detaining women whom they believed to be selling sex, and whom they then released and referred to services. The Times-Picayune reported:

"Two of the women, ages 21 and 24, were brought to Covenant House, a homeless shelter for young people at the edge of the French Quarter, according to executive director James Kelly. After taking a shower and spending the night, however, the women left without accepting the services Kelly and others were trying to offer them.

"'We believe they went back to turning tricks,' Kelly said. 'We did our best to try to care for them and try to get them to stay, but they were 21 and 24, and there was no way we could force them to stay, and neither could the FBI.'"

Looking at what happened in London, where sex workers turned down aid for fear of service providers cooperating with police, it's easy to understand why these women left the shelter. No matter how well-intentioned service providers are, accepting help from anyone who works with the police can be very difficult in a climate of heavy enforcement. Service providers may simply lack the resources sex workers need. When I reached Kelly by phone, he told me the women said they had a brother coming to pick them up, but that he thought they wanted "to go back out and make money".

We don't know what will happen to these two women, whom the press and police described as "rescued", or even if they needed rescuing. But we do know, for sex workers who need help, who are trying to get into a shelter or a health clinic, the support they seek is compromised by police raids, and by the environment of distrust and fear thus amplified.

This cycle has played out before, and will likely play out again. The Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women issued a 2011 report (pdf), after similar fears and crackdowns during the Olympics in Greece and Canada, and in the World Cup in South Africa and Germany (where experts expected some 40,000 women would be "imported" for the event"). GAATW looked at the data on sex work, migration, and arrests around these events, along with several past Super Bowls, and concluded:

"Based on available information (including anecdotal reports), many sex workers report being surprised and disappointed at the lack of business during large sporting events. In any case, any small increases in the demand for paid sexual services have not reached the extremely high levels predicted by prostitution abolitionist groups."

Brazil – which will host the World Cup in 2014 and the Olympics in 2016 – may provide an opportunity to break the cycle. Prostitution is legal in Brazil (though running a prostitution-related business, like a club or brothel, is not). Brazilian sex workers have some political power: they influenced the Brazilian government to reject $40m in Aids funding from the US, because to accept it would require Brazil to sign an anti-prostitution pledge, and Gabriela Leite, of the Brazilian sex worker organization Davida, was the first sex worker to run for Brazilian Congress.

There's some discouraging signs, too: in addition to providing cover for crackdowns on sex workers, major sporting events also make it easier for politicians and developers to target low-income neighborhoods for "redevelopment". In Rio de Janeiro, Global Voices reports that in advance of the Olympics, "communities earmarked for eviction and removal by the city" have been removed by tractors and riot police. It's estimated that as many as 170,000 people could be evicted in "preparation" for the 2016 games.

Residents of Brazil's favelas are not giving in. Cenira dos Santos, who owns a home in the Vila Autódromo settlement, told the New York Times:

"The authorities think progress is demolishing our community just so they can host the Olympics for a few weeks. But we've shocked them by resisting."

But perhaps the most positive sign complicating the fantasy of the "flood" of sex workers is a recent story out of Brazil: in anticipation of games-related tourism, the AP reported that 20 sex workers had enrolled in free English classes. The news took a respectable run around the web – and blogger Matt Yglesias remarked on the sex workers' business acumen, "It's not brain surgery."

Against the torrent of panicked stories about violence and degradation, peeping rescuers and aggressive police, the idea that sex workers might be making the same sort of pre-game preparations as anyone else is almost controversially ordinary.