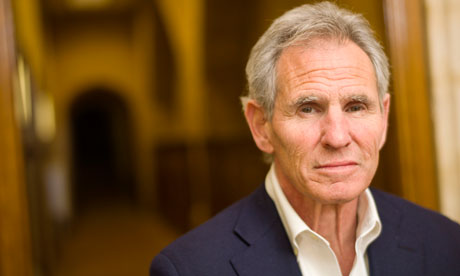

Back in 1965, a grad student in molecular biology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology stumbled across a class of five people on Zen Buddhism. He'd never heard of Zen and knew nothing of Buddhism. Nearly half a century later, that grad student, Jon Kabat-Zinn, has arguably done more than any other individual to put Buddhism into the mainstream, not just in America, but in dozens of countries around the world. Now, Downing Street policymakers are keen to hear more.

"That first class took the top off my head. I found a sense of largeness beyond my little preoccupations of what would happen to my future, or my relationships," says Kabat-Zinn. "It opened up a new dimension of being which could offer more meaning and enable me to interface more effectively with society in a way which could be healing and transformative."

Kabat-Zinn's enthusiasm for that dramatic breakthrough is still palpable as he talks of how as a scientist he resolved to find a way to bring those benefits to millions of others. What he evolved over the next 15 years was the Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) programme; an eight-week set of meditation and yoga practices in classes and at home, which instil the basics of paying close attention to the current moment.

"I was teaching molecular biology of muscle development in medical school at the time, and began to ask doctors: 'What percentage of your patients do you help?' They thought it was about 15% to 20%."

So Kabat-Zinn set up a clinic to help the untreatable majority. "Patients turned up with all kinds of conditions: hypertension, cancer, anxiety."

As a scientist, Kabat-Zinn knew he needed evidence; anecdotes and testimony were not going to be enough to persuade the American health establishment. "I wrote up the chronic pain results first because they were astonishing." Since then, a steady stream of academic papers, books and, more recently, randomised control trials, have helped pave the way for hundreds of MBSR programmes in hospitals and medical centres across the US.

Kabat-Zinn's work has spawned a cluster of different applications of mindfulness training, including for addiction, the elderly and parenting. In the past couple of decades, Kabat-Zinn has collaborated with psychologists in the UK who have adapted his work for Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), which has won recognition from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice), as a treatment for depression.

All of which explains why our interview is happening in Westminster, where Kabat-Zinn has a string of meetings with senior politicians before he heads to Downing Street for a session with policy advisers. There are good reasons for the policymakers to be listening closely, as Kabat-Zinn and his colleagues have a compelling proposition: mindfulness has unlimited applicability to almost every healthcare issue we now face – and it's cheap.

"The find it, fix it model of medicine doesn't work any more. The US healthcare system is bankrupting the country, bankrolling the insurance companies and exhausting healthcare staff," says Kabat-Zinn. "And despite all that, we are ranked 50th in the world for life expectancy."

The UK has huge challenges in healthcare, with an explosion in mental illness and an ageing population, he points out, adding that mindfulness is relevant to the debate about how to instil compassion and attentive care in healthcare workers to avoid a repeat of the Mid Staffordshire scandal. Mindfulness training inspires compassion, he argues. Just the act of being in the moment and paying attention to that moment allows the innate compassion within us all to emerge.

"It's all about training what you pay attention to," he says, admitting that this goes against the grain of a culture that trains us to privilege thinking and which offers endless opportunities for constant distraction from the present moment. "It's common sense. It's not about cures, it's about over time developing a different relationship with one's experiences, whether that's anxiety, pain, stress or depression. We know that changes the shape of the brain, it affects the behaviour of cells."

Kabat-Zinn has been one of the leaders of the dialogue between science and Buddhism, in which the Dalai Lama has been an enthusiastic participant. But it is the insistence of a very practical approach that has perhaps been the key factor in his success. Kabat-Zinn wanted to translate the Buddha's central insight, mindfulness, into a language that anyone could grasp. That's why he stopped calling himself a Buddhist; this is about being human, he says.

He now believes that mindfulness is on a steep adoption curve. Given the benefits of mental clarity, insight and creativity that practitioners claim, the interest from corporations is wellestablished, particularly in Silicon Valley, where Kabat-Zinn is a regular speaker. Even the US military has adopted a version of mindfulness for training soldiers.

None of these applications faze Kabat-Zinn, although they are far from the ethos of his own work. Even if mindfulness is used by the banker or the soldier to improve their professional skills, he says, it will also nurture the innate compassion of their humanity.

"It is what makes us human, what distinguishes us from other animals. We can be aware of being aware."