The idealisation of the natural world is as old as the city, to the corrupting influence of which a return to pastoral life is always presented as a cure. But the increasing modern appetite of metropolitan readers for books about walking around and discovering yourself in nature is the literary equivalent of the rise of the north London "farmers' market". Both feed on nostalgie de la boue – the French term for a kind of rustic-fancying inverted snobbery, which literally means "nostalgia for the mud". In the case of the urban consumer of nature writing, of course, the mud is to be hosed off one's mental Range Rover immediately one lifts one's eyes from the page and gives silent thanks for the civilised appurtenances of hot yoga and flat whites.

Much of the pastoral literary genre has long been a solidly bourgeois form of escapism. But nature is today also the arena for an oddly sublimated politics, and recent nature writing reflects some peculiarly modern concerns – sometimes in a way that the nice liberal audience would surely disown if applied to human affairs. In an era of immigration anxiety, for example, the ubiquitous ecological rhetoric of "native" and "invasive" species projects on to the natural world the patterns of human geopolitics. People talk of the grey squirrel as though he were the Middle Eastern asylum-seeker or eastern European plumber of tabloid hate-mongering, come over here as a benefits tourist or cunning job-thief.

Consider, too, the poor sheep, target of George Monbiot's passionate scorn in Feral, his recent manifesto for "rewilding" (bringing back animals that were once native, such as wolves). "I have an unhealthy obsession with sheep," Monbiot writes. "I hate them." Why so? "Partly as a result of their assaults," Monbiot laments, evoking a picture of serried ranks of sheep marching militaristically over the hillsides in coordinated attacks, "Wales now possesses less than one-third of the average forest cover of Europe." Sheep have been able to wreak such devastation, he says, "because they were never part of our native ecosystem", and so "the vegetation of this country has evolved no defences against sheep."

So goes the green version of the English Defence League: sheep aren't natives! They are "a feral invasive species". They don't belong here. "Invasive species," Monbiot complains, "challenge attempts to defend a unique and distinctive fauna and flora" – just as anti-immigration demagogues claim that foreigners will destroy a unique and distinctive British culture. "Certain animals and plants," Monbiot warns us, even "have characteristics that allow them to invade" – what, like Panzers and U-boats? – "and colonise many parts of the world." Thus each ecosystem is conceived as a little Westphalian nation state, vulnerable to assault by expansionist outsiders.

Monbiot tells us, though, that his despised woolly jumpers arrived in the British isles during the Neolithic period. That means sheep have been here a damn sight longer than Saxons. If the sheep aren't native, a lot of Britons aren't either. At least he doesn't want to send all the "invaders" back where they came from. He accepts that successful immigrants such as "grey squirrels and red signal crayfish" can't be got rid of; indeed they "now belong to ecosystems from which they used to be absent". So they "belong", even though they still aren't "native". It would probably be a kindness to standardise the situation by instituting a citizenship test for grey squirrels, after which they may be naturalised and given a passport.

What irks Monbiot about the insatiable hunger for lebensraum of "invasive species" is, finally, just that they will make everything duller to the eyes of naturalist aesthetes. "There is a danger," he writes, "that ecosystems everywhere come to contain a similar set of species, making the world a blander and less surprising place." Indeed, the spark of his desire for "rewilding" is, as he readily confesses in his intellectually generous and disarmingly enthusiastic book, that it would bring him more aesthetic pleasure. He came to the idea in the first place because he felt "ecologically bored". What could, on the other hand, be less boring than seeing the sabre-toothed tiger roaming the streets of Shoreditch, the hippo snoozing outside the Hippodrome?

To be fair, Monbiot does not recommend the reintroduction through genetic jiggery-pokery of prehistoric animals, though a real-life Jurassic Park would seem to fulfil perfectly his desire to rewild areas of unproductive land for the entertainment and edification of anomic city-dwellers. (Are not dinosaurs even more "native", at least in the sense of having lived here longer ago, than the red squirrel?) And, though hippo bones have been discovered underneath Trafalgar Square, Monbiot does not recommend the animal's reintroduction to Britain, because there isn't much in the way of suitable habitat, and also hippos are very dangerous.

But this brings us to the central tension in his book. On one hand, nature is considered as something we should not attempt to manage – what is wild is just what is not cultured. Rewilding, Monbiot promises, "is about resisting the urge to control nature and allowing it to find its own way". There is a certain smug hands-off paternalism to this image, as though the rewilder is watching from a safe distance while nature, like an adorable little child, wanders off haltingly on its own path. But the rhetorical anti-managerialism is everywhere undercut by the explicitly described managerialism of rewilding. Choosing just which plants and animals to "reintroduce" certainly sounds like "managing" the ecosystem. Even more so does "culling exotic species which cannot be contained by native wildlife". The euphemism "cull" for kill is presumably allowed in the context of liquidating troublesome foreigners.

Amy Leach's superficially very different book Things That Are, a collection of short whimsical pieces about animals, could be read as attempting a rewilding of the reader's imagination, through the ancient device of anthropomorphism. In Leach's world, goats and trees think, and birds are no less human than people, who are no less animal than birds. "Sometimes ostriches start twirling, or running in circles on the sand," she writes. "Who can twig the intricated soul of the pirouetting bird? A little is known about the rotary impulse in other creatures, like lost people." Later, she describes sleeping frogs wryly as trying "to screen themselves behind leaves and rocks, to hide from people who want to poison each other with frog poison".

Such cute touches are also occasionally on display in Tim Dee's forthcoming book, Four Fields, in which he roams a field in the Cambridgeshire fenlands, another in Zambia, one in Montana and one near Chernobyl. Dee watches wildebeest arriving at a river: "They stopped, as if waking from a trance. How did we get here? Why did we come?" And even the atmosphere has thoughts: "The fog was everywhere but thickest on the fen, for that is the lowest ground and the air knows it – the land has been underwater before." In both Dee's ecological musings and Leach's relentlessly winsome jeux d'esprit, such ascriptions of mind to life forms and the elements can be read as an attempt to invoke sympathy with the natural world, which might work more successfully for some readers than a straightforward harangue.

Leach also offers a satire on the way Monbiot-style attempts to artificially recreate an authentic wilderness might snowball:

"To prevent other tortoises … from becoming similarly rare … some people have proposed the importation of dingoes. The trouble is, after the dingoes finished the goats they might eat the natives, so crocodiles would have to be introduced to eat the dingoes. A succession of increasingly dangerous animals would have to be sailed to the island until someone would inevitably have to bring thirty hippopotamuses across the ocean and set them loose to squash everything, a stable but sad climax."

So who should really be in charge? Monbiot claims that rewilding "lets nature decide". But is letting nature decide such a good idea? After all, nature tried to kill us all with the Black Death. Nature is currently experimenting feverishly to find just the right strain of avian flu to cause a global pandemic. "Nature," as the young microbiologist points out in the zombie film World War Z, "is a serial killer."

Nature writers do tend to whitewash the non-human world as a place of eternal sun-dappled peace and harmony, only ever the innocent victim of human depredation (Leach even says nature is like a "hostage" and we her "captors") – always somehow forgetting that nature has exterminated countless members of her own realm through volcanic eruption, tsunami, or natural climate variation, not to mention the hideously gruesome day-in, day-out business of parts of nature killing and eating other parts. It was, indeed, the disgusting torture-porn brutality of nature that shook Charles Darwin's religious faith. "I cannot persuade myself," he wrote, "that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created parasitic wasps with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of Caterpillars." You don't get special treatment from nature just because you're a native.

If you go back far enough, human beings aren't native to any part of the world except Africa. So we must be among the most invasive species of all. We're eternal immigrants to a nature where we don't belong. This assumption, too, is common in modern nature writing. We are interlopers, intruders. Nature is no longer our home. "All fields," Dee writes, "tell of how we have orphaned ourselves from the world."

Indeed, many writers implicitly prefer a nature cleansed of human presence. In Rebecca Solnit's recent memoir of illness and travel, The Faraway Nearby, she describes walking on a deserted beach in southern Iceland: "It was as close to a vision of paradise as I've been granted with my eyes open." Paradise, it seems, has no people in it. The more deep-green eco-catastrophists of our time even seem to take a certain perverse pleasure in predicting that, one day, wise old Gaia will find a way to rid herself entirely of the human infection. We're merely renters in a righteously hostile world, with no security of tenure and a capricious landlord.

Such anxieties might have been deepening over the last years in which a new world of ambient virtual information has seemed to render our daily experience ever more abstract. Now we live in the cloud, still further from the soil that once nurtured our ancestors. You can hear such a shift in sentiment in the lyrics of the American rock band the Strokes. On "Heart in a Cage" (2006), Julian Casablancas sang plaintively: "See I was born in a city but I belong in a field." But by 2013's "Partners in Crime" there was no more belonging to be had: "Let's all be honest, where there's a forest, we don't belong."

Some of us, then, become all the more nostalgic for an imaginary Edenic life in which we were welcome in nature's bountiful embrace. Thus the genre of pastoral literature (which characteristically portrayed poor countryfolk, like shepherds, as the last authentic belongers), and the historically more recent "Back to the Land" movements, according to which a concerted fetishisation of dirt and dung might cure our urban-induced alienation. They initially sprang up in response to the Industrial Revolution, and saw a revival of agricultural cooperatives and handicrafts – foreshadowing the fashions today for "heirloom" turnips, "artisanal" cupcakes, and macrame classes. By the 1930s, unfortunately, the most vocal back-to-the-landers were fascists, in Britain and elsewhere: only by protecting and nurturing the national soil, it was argued, could we guarantee the ongoing purity of the national bloodline. (The "invasive species" here were Jews and other undesirable humans.)

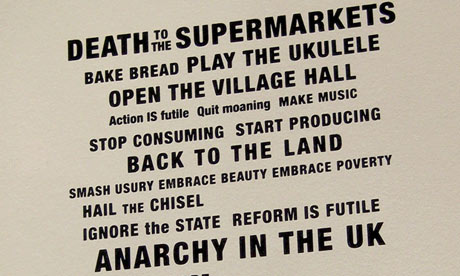

Today's back-to-nature revival is a response to corporations and the financial crisis: the global machine of mass "productivity" is broken, so we should retreat to our gardens and tend our organic carrots. "Death to the Supermarkets" read one poster recently on display in the "Idler Academy" in London. "Bake Bread, Play the Ukulele." (I can just hear it now.) "Hail the Chisel." (Is a chisel really natural?) "Hail the Horse." (Is a horse truly native?) "Anarchy in the UK." (I suppose we will still need electric sound systems, to play the Sex Pistols on.) "Stop Consuming, Start Producing. Back to the Land." Overall, it sounds rather enjoyable, like a rustic punk barbecue.

The idea that we are apart from nature and either don't belong in it or need to make a conscious effort to reintegrate ourselves with it, however, is tenable only once you have made the erroneous assumption that nature is exclusively medium-sized. Conceive of nature as basically the charismatic mammals and plants, plus a few pretty fluttering insects, and perhaps it's hard to see our place in it. But your body contains 10 times as many bacterial cells as human cells. Bacteria are part of nature, too. We are already ambulatory ecosystems.

It's also reasonable to ask how we could be fundamentally separate from nature given that we are naturally evolved creatures. Isn't nature working through us as much as through the honeybee? (Monbiot does not like the human attempt to "control" nature, yet he seems quite at ease with the heavy landscape-engineering of the badger or the termite.) And if nature is smaller than usually assumed – down to bacteria and viruses – it is also bigger. Solar systems and galaxies are part of nature, too. On the cosmic scale, some philosophers speculate that the appearance of conscious, inquiring human minds could be part of some deep evolutionary process whereby the universe comes to know itself. Feel at home yet?

The fear that Julian Casablancas of the Strokes expresses, that we just don't belong in the forest, is for some people the whole point. That's why we should go there. Nature functions not as a homecoming but as a temporary retreat. Here you can forget the clutter of civilisation. A nature away-day affords a meditative cleansing, the annihilation of self-consciousness. While fishing in the sea, Monbiot recounts gladly, "My mind blew empty"; while rafting down the Colorado river, Solnit reports, "The flow of water seemed like the flow of time, as though I had left behind the particulars of my life to step into life itself"; star-gazing in Africa, Dee rhapsodises about "the oldness of the view, the way looking up shreds your life, strips it back".

More extended excursions into the forest see nature providing an arena for the elaborate performance of solitude, a backdrop to the drama of the self's encounter with itself. Cheryl Strayed's Wild, a recent number one New York Times bestseller, recounts the author's months-long trek in the American wilderness in search of what she calls "radical aloneness", and in order to escape from a "mixed-up life". (In the wild, she reports, you can't numb the pain with a martini.) That aloneness can be radical is also the theme of the German writer Ernst Jünger's 1954 pamphlet "The Retreat into the Forest", which uses forest-going as a metaphor for political and cultural dissidence. It is also necessary, he writes, as psychic training, so that one can be a better human being once re-emerged from the treeline:

"The great experience of the forest consists of the encounter with the Ego, with the self, with the inviolate core and essence that sustains the temporal and individual appearance. This encounter, so decisive for the conquest of health and for the victory over fear, is also supreme in its moral value. It leads to the primal basis of all social intercourse, to the man whose example defines individuality … the Ego recognises itself in the other human being in the saying, 'This is you.'"

Jünger was one of the authors the French writer Sylvain Tesson took on his own retreat into the forest, spending six months in a one-room cabin in the frozen Siberian wilderness. His diary of this time is Consolations of the Forest: Alone in a Cabin in the Middle Taiga. In the bleak purity of nature, he expects to encounter his self ("I will finally find out if I have an inner life"), and in joyous reverie he enacts a Nietzschean revaluation of modern values. "In the hammock, I study the shapes of the clouds. Contemplation is what clever people call laziness to justify it in the eyes of the supercilious, who watch to ensure that we all 'find our place in an active society'."

Occasionally, Tesson visits his nearest neighbours – who would probably not be enthused by any Monbiot-style rewilding project, as they already have to deal with frightening incursions by wolves and the brutal killing of their oxen by bears. Otherwise Tesson's is an alternately rapt and sardonic diary of solitude, fortified by vodka and books. "Eremitism" – being a hermit – "is elitism," he points out. But at least, as part of the elite who can undergo such immersive nature tourism, he has found out a few things on our behalf, which he expresses in punchy aphorisms. "A free man possesses time. A man who dominates space is merely powerful."

And so the returning nature-writer brings back to the eager denizens of Stoke Newington or Brooklyn some long-forgotten truth from earlier times – which in myth are always wiser times. Thus he acquires something of the aura of a guru. A figure such as Robert Macfarlane becomes in the public eye both a successful and widely admired author, and a spiritual role model of faintly druidic mien. Macfarlane's latest book, Holloway (co-authored with Stanley Donwood and Dan Richards), sees the celebrated rambler exploring old sunken paths in Dorset, and musing freely. "One need not be a mystic," he suggests, "to accept that certain old paths are linear only in a simple sense. Like trees, they have branches and like rivers they have tributaries. They are rifts within which time might exist as pure surface, prone to recapitulation and rhyme, weird morphologies, uncanny doublings." (Dee, too, sees nature as a defeat of time's arrow: "All fields are places of outlasting transience. They reset time.")

True to the genre's form, Macfarlane at length fetches back some old natural wisdom: "I now understand it certainly to be the case, though I have long imagined it to be true, that stretches of a path might carry memories of a person just as a person might of a path." And so mind – just as with Leach's ascription of reflective consciousness to animals and plants, or Dee's self-questioning wildebeest and knowledgeable gas – is understood to be spread out everywhere in nature, rather than a possession only of human beings. It's probably always a strong temptation for nature writers to flirt with such panpsychism. That's one way, after all, to reassure ourselves that, even in the solitude of the modern city, we are not alone.