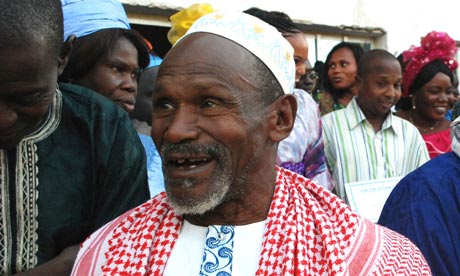

"A person's family is not their village. The family includes one's entire social network: their relatives in many surrounding villages, in all of the places they marry, even in far off countries like France and the United States ... If you truly want to bring about widespread change ... they must all be involved," says Demba Diawara, Senegalese village chief and imam.

He describes how social change can occur within communities. He applied this idea in 1997 and 1998, reaching out within his social network to end female genital mutilation or cutting (FGM/C) by mobilising 13 communities to make a public declaration to end FGM/C. This process has now been replicated many times by others, leading thousands more to publicly abandon the practice.

Demba's is an exciting, expansive, yet challenging strategy. To change his community, he must change his entire extended family network, which in west Africa means a lot of people.

At Tostan we have worked constantly with leaders like Demba and those who have followed in his footsteps. They explain their work as reaching out to their extended family to engage them on vital issues necessary for community wellbeing. It sounds straightforward but this oversimplifies it. Often, the better we know someone, the harder it can be to bring up a challenging subject. Issues that touch on values or social norms can cause tension, especially when family history and tradition are involved. It varies by family and by society, but there are some issues we hesitate to raise at all.

So how exactly did Demba approach his work on such a sensitive issue? Well, first, he identified the groups most necessary to his cause. He deliberately went first to his father's lineage, then to his mother's. He spent four months walking, joined by two of his peers, going from village to village. He focused on providing good information from reliable, verifiable sources like local health agents and religious authorities, and then let people draw their own conclusions. He framed things in relation to shared values, as well as human rights and responsibilities.

This built upon the education he had received as part of Tostan's nonformal education programme. It certainly helped that he was a respected religious leader and could speak to the fact that "the tradition" was not mandated by Islam; however this did not guarantee his success, and in the years since Demba first shared his theory with us, we have found that many others can play this role. Passionate grandmothers and mothers, former cutters, and enthusiastic youth groups have used Demba's approach with great success.

What is central to the work of all of these individuals and groups is a passionate defence of human rights and a clear sharing of the consequences of the practice of FGM/C. This is framed within the traditional values that hold these families and communities together rather than in language that attacks or shames from an outside point of view. As Maimouna Traoré, a woman who early on joined Demba's efforts to see the end of this practice among the Bambara people, put it: "In giving up this tradition we are not less Bambara. We are now more Bambara than ever."

All of the above strategies rally the network towards a crucial moment – a public moment to mark the social shift. A moment after which it finally becomes acceptable to give up FGM/C. A moment after which there is a real choice. This has become known as the public declaration or pledge.

The importance of public declarations cannot be overstated. There have been over 60 of these related to Tostan's work to date and evaluations have shown that the host communities and their close networks do end the practice. Earlier this year, and this is a testament to Demba's theory in practice, there were four public declarations in four different countries in west Africa. Communities in Guinea, Mali, Senegal, and Gambia all stood up to declare abandonment of FGM/C and child/forced marriage after participation in Tostan's three-year programme.

New ideas spread widely through interconnected communities and groups, even when these groups extend across borders. We have taken Demba's theory and our learning from the past 15 years and applied it to our Generational Change in Three Years campaign which aims to partner with 1,000 communities at the same time across the region to bring about large-scale social change. Focused on six countries in west Africa, we are confident we will see a greater momentum towards the total abandonment of FGM/C in the region.

Working on a social norm like FGM/C requires working via social networks but we are finding that other issues – like education, child protection, and violence reduction – can also benefit from a similar strategy. In the end, like most brilliant insights, Demba's strategy has the feeling of being revolutionary and also second nature. People in your networks are the people that matter most and if your change strategy removes them from your network, or you from their's, the very fabric of your connection, and your ability to influence, is lost.

Gannon Gillespie is Director of Strategic Development at Tostan. Follow @gannongillespie on Twitter

This content is brought to you by Guardian Professional. To get more articles like this direct to your inbox, sign up free to become a member of the Global Development Professionals Network