Life is a career that none of us chose. We are thrust into it, wailing in protest, and get little enough vocational training. The rich and credulous hire life coaches to flatter them; others who crave enlightenment can sign on to be educated at the School of Life, set up by the entrepreneurial egghead Alain de Botton. It's a full-service establishment, which pseudo-technologically supplies "tools for thinking" and also, in a shop attached to its Bloomsbury classroom, sells pencils that its customers can chew while they cogitate.

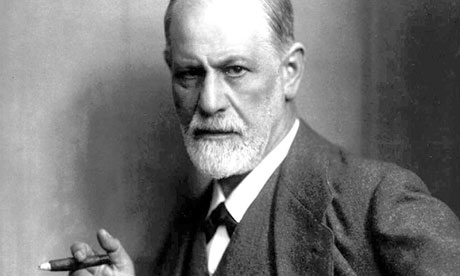

Now this emporium of self-improvement is issuing books that fillet philosophers and apply their theories to daily conundrums. Brett Kahr, for instance, reveals that we can learn from Freud "how to love another man's wife" and "how to erase your entire family" (which most of us could probably have managed by using animal cunning, once known as mother wit). Robert Ferguson recommends Kierkegaard because he teaches us "why we should cultivate dissatisfaction", and Michael Foley – riskily, I'd have thought – urges Henri Bergson and his vitalist theory of comedy on office workers who are "learning to laugh through departmental meetings". John Armstrong, reducing Nietzsche to bullet points, issues an admonition that could be as disastrous as tittering while your departmental head drones on: "Be Noble Not a Slave," he advises. If only a pedigree and the perks that go with it were so easy to obtain!

Stretching across the gap between the academy and the home or workplace proves uncomfortable, and the authors of these "thinky books", in Foley's defensive phrase, are keen to ingratiate. Some begin with embarrassed jokes. "Who was this guy?" asks Foley about Bergson, and Armstrong quotes Monty Python to remind those who can't pronounce Nietzsche's name that it rhymes with "teach ya". Kahr tells a story about being snubbed by a snotty don when he first mentioned his enthusiasm for Freud, then tries out his therapeutic skills by explicating Hugh Grant's cheap but disastrous kerbside date with the prostitute Divine Brown.

Hannah Dawson initially apologises for inflicting "nasty, brutish Hobbes, the Monster of Malmesbury" on us, but goes on to say that she broods about his philosophy of power whenever she is menaced by a red bus while cycling through central London: such high-mindedness makes me fear for her safety on the road. In a wry recognition that thinking cannot be detached from the muddle and mayhem of daily life, she also notes that her book – the best of this bunch, trenchantly confronting contemporary political problems – was written "to the bovine soundtrack of the breast pump".

Sages are sadly frail and faulty mortals, as we are frequently reminded here. Kahr emphasises Freud's infidelity with his sister-in-law and his fratricidal feelings about his brother. Nietzsche was mad, Byron was bad, and both were dangerous to know: should we really be learning lessons from them? Armstrong does his best to avoid mentioning Nietzsche's descent into mania, which he euphemises as "intense delusions"; Matthew Bevis ignores Byron's neurotic self-destructiveness and describes him as a poet of physical pleasure, who enjoins us to dance or to splash around in the water. The body thinks in its own uncerebral way, but does it need a literary critic to prescribe a night of clubbing or a day at the beach?

Light homework is handed out at the end of each volume. Ferguson supplies a playlist: apparently Bob Geldof's Boomtown Rats and Fleetwood Mac help us comprehend Kierkegaard. Kahr urges his pupils to "pop over to the Château Malmaison, outside Paris" to study David's portrait of Napoleon. The assignment set by Foley – who would really rather be writing about Buddha than Bergson – is "to experience mystical unity while reading the Persian poet Rumi, drinking champagne and doing a dervish dance". What the School of Life dispenses, evidently, is a tipsy version of Nietzsche's "gay science" or "happy wisdom", available to truth-seekers who can afford bottles of bubbly and Eurostar tickets.

Yet there is a good deal to be learned from these little primers. Ferguson writes well about Kierkegaard's claim that we sleepwalk through our days, which is truer than ever now that we are insulated and pacified by our battery of electronic comforters; surrounded by a "cacophony of digital sound and wind". We are in danger, Ferguson warns, of living virtual lives. Foley is equally sharp on Bergson's hostility to habit, and – again more Buddhist than Bergsonian – has excellent advice about how to appreciate the passage of time and the value of the moment: "I sit on a sofa at dusk," he says. "The gradual fading of the light is a perfect example of process." Anything that plugs in must be switched off, and the gradually condensing shadows make it impossible to read: some life lessons can't be learned from books.