Drawing, believes Andrew Marr, is much too important to be left to artists. Everyone should do it. The simple act of setting pencil to paper can change your life, maybe even help save it.

"After my stroke," he says, sitting in his modest but stylishly done-up suburban house in London, "I was lying in bed and just drawing pictures of the covers and the end of the bed: in a sense, nothing. But it starts you thinking, 'Oh yes, my mind's still there, I'm still engaging in the same way that I was.' I might not have the same skill because I can't move my arm properly, but the desire to do it is still there."

The morning is so pallid that the only colour seems to come from his collection of rollicking abstract paintings by Gillian Ayres. Marr is nursing his left hand as he explains how his illness, and slow recovery this year, affects his ability to make pictures.

"I can draw again all right, but because I still can't use this hand very well and it's not strong, holding the bit of paper or the notebook in one hand and drawing with the other is something I can't do. So I'll be drawing and the notebook will slip off my knees and I have to pick it up again. Sharpening pencils takes for ever. I drop things all the time, so I sit on a bench surrounded by pencils I've dropped, bits of rubber. It's a messier and slower business, but I can do it – which is great."

Then, in a bold thought that says a lot about him, he muses that having a stroke has actually made him a better artist. We talk about late Picasso, late Titian and late Cézanne, how they all got greater in old age; how his friend David Hockney says painting is an old man's game. He's not old – he's 54 – but just as age made his heroes paint more wildly, his temporary loss of function has forced him to be more daring.

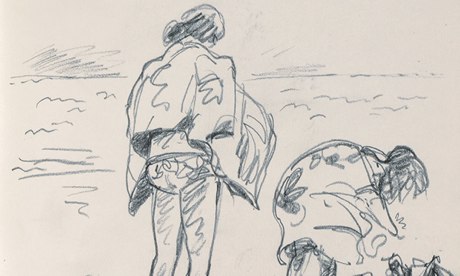

"I think that, since the stroke, I've loosened up a bit because, to be honest, putting one line on a bit of paper takes me a little bit more effort than it did, so you don't want to waste the effort. And my big problem as a drawer has always been to be finickity, too dibbity-dabbity as they used to say."

Marr calls himself a "drawer", not an artist. In fact, the whole point of his new work, A Short Book About Drawing, is that he is no artist – even though every illustration in it is drawn, painted or sketched on an iPad by him. Once, he argues, drawing was the basis of fine art. Today, it's barely taught by art schools, but that's a liberation for the rest of us: we can draw without having to judge the results as art.

Why should we spend our free time doing that instead of eating crisps and watching TV? Because, Marr believes, drawing – or any kind of skilled manual effort – frees you from the exhausting emptiness of modern life. He's amused when I say the book has "moral fervour". But it does. He tells me how western society with its obsessive consumerism and endless distractions totally misunderstands the nature of happiness. A truly happy life, he thinks, does not come from vacant chilling out: "It's not going and lying on a fucking beach, you know? It's not just lolling about. I think it comes from making things and being connected to the rest of the world."

He cites the American political philosopher Matthew Crawford who now works as a motorcycle mechanic and whose book The Case for Working With Your Hands argues that to be whole people, we have to make things. Yet Marr's belief that drawing is a life-enhancing discipline (he jokes about "the zen of drawing") would equally have delighted the Victorian socialist art critics John Ruskin and William Morris, who shared his belief that modern society has lost touch with what matters.

"When you are doing something that you've got some inclination or talent towards, but which is not easy, and you're therefore completely concentrating on making something – that is, I think, when most people are happiest." For a farmer in touch with nature or a drawer sketching a tree, "there's a dignity and a purpose to life, which you don't get from working in a call centre or being on television."

He laughs. Marr is not being vain in publishing his drawings: he makes no grand claims for them even though he has drawn seriously all his life and even considered going to art school, instead of Cambridge. "I still wonder if I might have been better off going to art college," he says.

In terms of happiness? "Yes."

A Short Book About Drawing, by Andrew Marr, is published by Quadrille