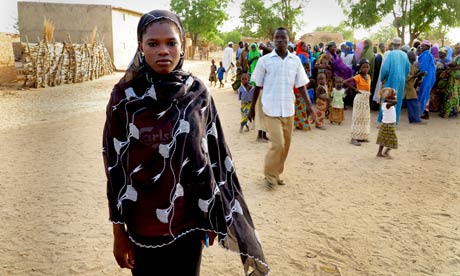

The number of girls giving birth before the age of 15 in sub-Saharan Africa will increase by more than 1 million by 2030 unless urgent action is taken to end child marriage, get more girls into school and ensure their rights are protected, according to the UN's flagship population report.

If current trends continue, the number of girls under 15 having babies in this region is projected to increase from 1.8 in 2010 to 3 million over the next 17 years. This would take the estimated total number of under-18s giving birth in sub-Saharan Africa to more than 16 million by 2030, up from 10.1 million in 2010.

The report, Motherhood in childhood: facing the challenge of adolescent pregnancy, published on Wednesday by the UN population fund (UNFPA), said major changes were needed in addressing teenage pregnancies.

Instead of blaming girls and trying to change their behaviour, the underlying reasons for pregnancy in the young needed to be tackled. This included keeping more girls in school until they are 18, providing quality sex education and access to health services, educating boys and men about girls' rights, and enforcing laws against child marriage.

Despite international commitments to end the practice, one in three girls in developing countries is married before the age of 18, and 50 million girls are at risk of being married before 15 between now and 2020, the report said.

"Too often, society blames only the girl for getting pregnant," said UNFPA's executive director, Babatunde Osotimehin. "In many communities and cultures, the status of women is such that everything that happens to them is considered their fault. But changing behaviour has been wrongly seen as the sole solution. [Pregnancy] is less to do with girls' personal behaviour and more to do with the behaviour of families, communities and governments around the world. Adolescent pregnancy is not only the result of recklessness, but an absence of choices."

Girls were often denied the right to decide when, and if, they had children because in many countries and communities they are still regarded as unequal to boys, he said. Girls who have babies when they are young have had their "rights violated and their future has been forever derailed". Boys must "be socialised to see girls as equal", he added.

Osotimehin said girls were particularly at risk of death and disability from early pregnancy. The report said early pregnancy increased the risk of maternal deaths and obstetric fistulae. About 70,000 adolescents in poorer countries die annually in childbirth or through pregnancy-related complications.

The report found that the vast majority of adolescent births occurred in developing countries, predominantly among girls from low-income households in rural areas, with little or no education. Nine out of 10 pregnant teenagers in poor countries are married or have a partner.

According to figures obtained by UNFPA through surveys in 54 countries, in 2010 36.4 million women aged between 20 and 24 and living in poorer countries reported having given birth before they were 18.

About 17.4 million were in south Asia, the region with the highest number of under-18 births. Latin America and the Caribbean had the lowest rates of pregnancy.

The survey figures also revealed that 3% of young women said they had given birth before they were 15. The report said that one girl in 10 had a child before the age of 15 in Bangladesh, Chad, Guinea, Mali, Mozambique and Niger, countries where early marriage is common. West and central Africa accounted for the largest percentage of reported under-15 births. Niger, which has the world's highest adolescent birth rate, also has the highest rate of child marriage.

"Many countries have laws against child marriage, but they don't enforce them," said Osotimehin. "Impunity is what reigns around the world. We must protect adolescent girls. Justice should prevail."

The report acknowledged the difficulties of obtaining information about girls aged between 10 and 14, but pointed out that not having this data rendered these girls and the challenges they faced invisible to policymakers.