Back around 510BC, when Rome was under the rule of the tyrannical Etruscan King Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, his son raped Lucretia, wife of a high-ranking consul. Noble and virtuous, a shamed Lucretia proceeded to commit suicide, but not before swearing the gathered Roman dignitaries at her father's home to vengeance against kingly tyranny. Her suicide thus marked the foundational moment of the Roman republic and took on legendary proportions. Livy recounted it as historical fact some 500 years later.

During the rediscovery of the ancient world that was the Renaissance, Lucretia became a favourite subject for the greatest painters: republican heroism, bare female flesh, a body marked as one's own rather than belonging to God and church, let alone passing males – Lucretia gathered all this into her image to become a pictorial champion of humanism. Botticelli paints her with flowing primavera hair, dagger in bosom, and stretched out on a black sarcophagus smack in the middle of a Roman forum where all around her men hold their swords raised as they swear to overthrow monarchy. Titian has her surprised in bed and struggling boldly against her dagger-wielding ravisher. Cranach the Elder shows her regally robed and stately, one bosom bared to the dagger she holds in her hand. Rembrandt paints her, already bleeding, as his mistress Hendrickje: destroyed by the power of disapproving burghers, she is a heroine of the intimate republic of (illicit) love.

But even this last, more modern, Lucretia is a far cry from her contemporaries on anorexia websites where the siren call to self-inflicted death is loud and clear. No longer a crime – either against God or society – suicide in the modern world has become a much mimicked escape route from a despair that can feel total and for ever. The human right to take one's own life, free of religious, state or medical control, championed since the Enlightenment, has been a fact in many jurisdictions since the 1960s. In tandem, the WHO tells us that rates over the past 45 years have increased by 60% worldwide. In 2001, the US numbered 30,622 suicides, a figure that rose to 38,000 in 2010, making it among the top three causes of death in the under-35s. That year, a US veteran killed himself every 65 minutes.

In her drive-through history of ideas about suicide, intellectual historian Jennifer Hecht sets out to show that if the Renaissance and then more emphatically the Enlightenment robbed self-murder of its medieval Christian status as devil's work, the subsequent understanding of suicide as the result of a "medical" condition, such as melancholia or depression, and as an individual right, has had nefarious effects all round.

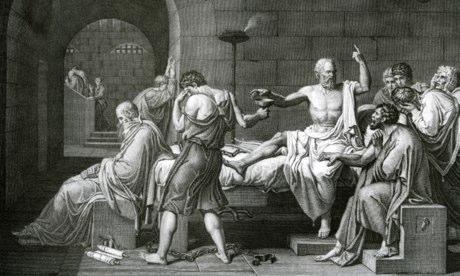

For the ancients, suicide was not a simple solipsistic escape for those weak of character: Socrates chose it as preferable to murder by the state, Lucretia in part to rally the republican troops; Cleomenes I, the Spartan king, rejected it in defeat for, as Plutarch recounts "it is an ungenerous thing either to live or die for ourselves". (Mad in prison, he later did kill himself.)

The early Christian martyrs may have marched willingly to death, but no sooner was Christianity instituted than Constantine made suicide a crime. Throughout the middle ages and until roughly 1750 (when the word also came into common usage), self-murder was Satan's work: suicides would be retried, though dead, then hanged, drawn and quartered, their property given over to the state. Only with the rise of a scientific and medical discourse, as evidenced in works such as George Cheyne's The English Malady (1733) where the rise of nervous illnesses, melancholy and suicide are all linked, did a modern notion of suicide come into being.

It seems that among the many other facets of contemporary life for which the Enlightenment can fashionably be blamed, high suicide rates now feature too. Of capitalist excess, joblessness, deadly institutions or families, pursuit of spurious happiness, rampant use of street drugs and pharmaceuticals, cyber-bullying, the decline of the polis, the new martyrs, there is no mention. Those old Enlighteners, after all, "enhanced the value of the self above that of the community and tradition and made of each man and woman an independent being".

Hecht's history of ideas rarely does enough justice to the intellectual heft of the holders of those ideas: Hume, Baron d'Holbach and other Enlighteners might have railed at their reduction and their slippage out of context. In this respect, Stay is a disappointing book. But Hecht's aim is to show that as suicide was secularised, it became too easy – a mere medical and therefore solipsistic condition which took no account of humans as members of a larger (caring) community. She wants to revitalise the idea that suicide is wrong, harms others and "damages humanity". No man or woman, even today, is an island. Her sentiment is laudable, though it sometimes overrides her history.

Lisa Appignanesi's Losing the Dead (Virago) is now out in a new edition. Her Mad, Bad and Sad has inspired the exhibition currently at the Freud Museum, London