As Mrs X begins to die in a lilac-painted hospital side room, surrounded by her husband and children who are perched on a semi-circle of purple plastic chairs, a team of surgeons and nurses is making preparations for her afterlife. In an operating theatre a few metres down the corridor, a six-person team of organ retrieval specialists has arrived to remove her kidneys, her liver and possibly her corneas.

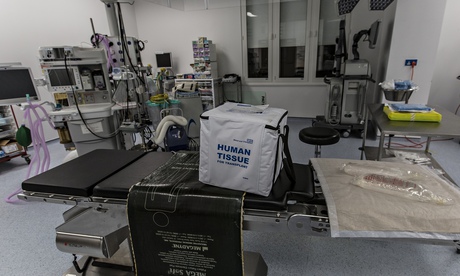

It is midnight on a wet weekday night, and it isn't clear how long they will be here waiting. Once the extubation process (the removal of the breathing tube) begins, death needs to happen within three hours or the organs will no longer be in a fit state to be used. A square bag, not unlike a picnic cooler bag, filled with ice, labelled Human Tissue, is prepared and a courier is on standby.

Hospitals around the country have already been contacted to establish where the organs should go, and not long after the nurses have switched off the breathing apparatus, Mr Y gets a phone call, telling him to pack his bags and make his way to hospital as quickly as possible. He is at a late-night church service, so he asks the pastor to drive him in.

Elsewhere, another possible recipient receives a midnight call, and is summoned to a third hospital to await the second kidney.

For the operations to be successful, the removal of the organs and the transplant must happen very swiftly. Complex arrangements begin around lunchtime when Mrs X's family are made to understand that there is no hope of her recovering from the catastrophic heart attack that brought her to hospital two weeks earlier, and agree that it is time to let her die.

She has signed the organ donor register, and the family have supported her request, so a specialist nurse for organ donation (shortened with the ugly acronym Snod), has been paged in to help them, and to launch the laborious job of searching for the best recipients. If a recipient is found on the other side of the country, then air transport will have to be arranged, because once the kidney is out of the body there is only a 12-hour transplantation window, otherwise its functions begin to deteriorate.

The Snod is here before the donor has died, before the recipients even know their lives are about to be transformed by the long-awaited arrival of an organ. He will be here for a day's work that won't end until early the following morning, supporting the family through the process, performing the last offices on the donor, washing and dressing the body and placing her in a shroud once the organs have been removed.

The family has had two weeks coming to understand that their mother will not survive, so they are better prepared for the process than many. Doctors have scanned her head, established that there is an unsurvivable brain injury, and concluded that it would be in her best interests to withdraw treatment. In her late 50s, the dying patient is not too old to donate her organs. "Kidneys have no sell-by date," a doctor says.

The nurse has spent much of the afternoon talking to them, explaining what will happen. Families find it easier to talk to nurses than doctors. "Sometimes you have to explain information again and again and again, because they are at a stage of such great grief that we have to ensure they have understood. Doctors are not very good at having this conversation. They use medical terms people don't understand. It is a lot of information to take in. The consultant on the intensive care ward will be looking after 22 people. Nurses have more time. Families feel they can ask the silly question," he says.

Some families are uncertain about what their relative would have wanted, and staff wish this was a subject people were more ready to discuss. "We are asking people to do something for others at a time that is so devastating for them. It is an awful time to be asking someone this information. A lot of families say no because they don't know what their relatives would have wanted," he says. NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) figures show that despite the fact that most people either want to donate their organs, or would consider it, only half have talked to their families about it. Figures also show that seven out of 10 families opt not to give permission for their relative's organs to be donated, if they don't know their wishes.

Fortunately Mrs X's family knows want she would have wanted and are anxious for as much of her body to be transplanted in new people as possible. "They are a lovely family. Really kind," the nurse says.

Following the journey of a transplant is a uniquely challenging journalistic exercise, not least because the timing of an operation is impossible to predict in advance and depends on human tragedy. There are very strict rules governing confidentiality, to prevent the family of the donor and the recipient finding out too much about each other. Contact between the two is rare, and only happens at the end of a very supervised process. To adhere to these rules, all names, locations and dates have been removed from this account, making this an uncomfortably detail-free article.

But there is a parallel desire from NHSBT to focus attention on the need to sign up new organ donors and to highlight the extraordinary life-prolonging effect of a successful transplant. Although there has been a 30.5% increase in transplants in the past five years, there are still more than 7,000 on the transplant list, and last year more than 1,300 people either died while on the waiting list or became too sick to receive a transplant. The process of signing up to donate is simple and takes only a couple of minutes online.

Earlier this year, the law was changed in Wales to introduce a system of presumed consent for organ donation, which will give doctors the right, in principle, to remove people's organs when they die unless they have registered an objection. Supporters of the new policy, which will be introduced in December 2015, believe that it will save lives; opponents worry that it could intensify the anguish of some grieving families. France, Spain, Sweden, Italy, Belgium and numerous other countries have already adopted the system. In England, the debate continues.

By early evening, the final medical checks are done on the dying woman, and the nurse sends out a list of possible body parts that might be suitable for transplant to an organ donation coordinating hub in Bristol. He receives back a list of hospitals, caring for possible recipients, and begins to call consultants to tell them what is on offer, and to see if they want to accept it on behalf of a patient.

Until this is all in place, the family must wait, before the breathing tubes are removed and their relative is allowed to begin the process of dying. They are encouraged to go home for a while, before returning to sit in the depressing waiting room, drinking cherry cola and Ribena, watching a muted television in the corner. A homemade sign, decorated with a sketch of a fluctuating heartbeat line, promises: "Throughout Your Loved One's Journey, There May be Ups and Downs, However We Will Endeavour, To Make It as Smooth as Possible."

Staff know that this wait can be agonising and try to prepare them for it. "Sometimes they withdraw consent if the process takes too long. We do tell them the process takes a long time," the nurse says. By 10.30pm, recipients have been found for the two kidneys, but no home has been found for the liver.

He begins instructing the retrieval team on this basis, but is interrupted by his mobile phone. "Really? That's fantastic. Anne, you have made my day. That is amazing," he says, smiling into the phone. "The breathing is fading a bit. We'll do the extubation between 11.30 and 12 ..." The surgeon in Birmingham who was previously offered the liver has changed his mind, and decided to accept it. "That's good news for two reasons. It could save someone's life; also it helps the family who are very keen for the donation to happen," he says.

At around midnight, the breathing tube is removed from Mrs X's mouth, and the family is called back to be with her for the final process. "I don't do anything to accelerate her death. We ensure that she is comfortable, but we don't do anything else." She lies on the bed, with a pile of soft toys on her feet, breathing independently. There is silence apart from the whir of the air conditioning, and the high chirruping from medical equipment in the room, echoed by cheeps in the ward across the corridor, like electronic birds answering each other's call, wearyingly unceasing.

Her eyes are shut. The nurse notes that the oxygen levels are dropping quite quickly. At some point in this hospital's long history, someone decided it would be soothing to paint the wards with a lavender paint. Now the pale pink is criss-crossed with old plug sockets, bits of dried-up Sellotape, and endless bossy public health instructions, hand-shaped stickers that instruct visitors to "Stop and Wash! Do your bit!" and to "Switch It Off! Making Business Sense of Climate Change". She dies surrounded by scuffed grey lino, bright yellow binliners, a box screwed to the wall dispensing white plastic gloves, breakfast trolleys pushed into the corner, and the orange glow of street lights outside, rain dripping down the windows.

Family members come out to the corridor, for a break from the pressure. Something is ending here, but not quite ending. Naturally, there is none of the joy of a maternity ward, but there is a sense of expectation, of new life beginning.

In the cool ante-room outside the theatre, the young surgical team are briefed on her medical details and told which organs should be retrieved. The last stage of life turns out to be very quick, and is over within 30 minutes. Doctors start removing Mrs X's organs at around 1am. It turns out that the liver is not good enough to transplant, but the kidneys look in very good condition.

A beautiful procedure

Later that night, in another hospital, somewhere else, Mr Y is mentally preparing himself for a major operation, which has inevitably come without warning. He is lying in a room that he has to himself, still dressed, a thin hospital blanket pulled over his clothes, when I'm taken in to meet him at around 4am. He is awake, but was initially (understandably) not desperate to talk to me. The prospect of having a major operation you were not expecting to have just a few hours ago is dispiriting enough without being asked to describe how you're feeling to a journalist in the early hours of the morning.

After a reassuring conversation with the surgeon, he is very obliging, however, and explains how he went to the doctor a few years ago with swollen legs and a puffy face, and discovered he had high blood pressure and that his kidneys were no longer working. He hadn't realised anything was seriously wrong. "It is the silent killer," he says. He has been on dialysis for two years.

He had worked as a warehouse employee but lost his job recently. In any case, dialysis had made work exhausting. "I'm always tired. I feel very weak and sleepy as well. Dialysis is very, very time-consuming. You're stuck to a machine all the time. I don't feel happy, but you get used to it, because if you don't, you can't survive."

He has been looking for new work, but a lot of jobs he can't apply for because the three weekly visits he needs to make for dialysis eat into his working hours. His illness also makes interviews complicated. "If you disclose your sickness, they will not call you back, because they think your performance will be low. But if you don't disclose your illness and they find out, they can terminate your contract. You are stuck between two positions.

"My mind was not on transplants at all. The doctor told me that it would be difficult and I would have to wait a long time," he says.

He regrets not having taken his health more seriously. "The car goes to an MoT; every six months, you should get into the habit of doing the same, visiting your GP. I didn't go to the doctor. I should have gone to the doctor."

He isn't curious about the donor family or the circumstances that have made the organ available. "I don't want to know anything. I just don't want to know."

This is not unusual, a consultant at the hospital explains. "They tend not to ask. I suspect it is because they want to dehumanise it a little bit – take the organ now and deal with the human side later. It is emotionally challenging as it is, to be called in for a transplant, without thinking about the donor family's grief. There's a lot to cope with already."

The surgeon reports later that the procedure, which began at 8.30 the following morning and was over by 11.30, went "beautifully". He was thrilled at the state of the kidney. "It was really a wonderful organ," he says with unexpected delight.

His description highlights both the amazing simplicity of the process – pulling an organ out of one body and popping it in to someone else a few hours later – and the extraordinary sophistication required to make it work.

The host of the kidney has changed gender. It has left the body of the woman, where it has grown for the past five decades and been sewn into the body of a sick man. The surgeon could tell that the kidney was not in its first flush of youth – it had lost its pearly sheen, and there were traces of scarring – but it was functioning well. "The donor was a good donor. This was an excellent kidney, beautifully retrieved," he says.

When the transplant box arrived, he had to check that it was the correct organ, coming from the hospital he expected, checking that it was the right kidney, as promised, and not the left one. The kidney was not ready for transplanting, so he worked with colleagues to trim it, remove all the fat, expose the anatomy, check the vein, the artery, the ureter, and repair anything that was damaged.

Transplanting an organ is less traumatic than removing one (several doctors use the word "harvesting", although one corrects himself, apologetically: "Harvesting – I try not to use that word, it sounds like a 1970s cloning film"); the old kidneys are left in the body. The critical moment comes towards the end, when doctors release the clamps, the instruments that hold the blood flow, and allow the blood to rush into the new organ. "You don't stop to think 'this is fantastic' and have a moment of happiness. It is a moment of attentiveness. You are too busy, you need to make sure you do a good job," he says. "When you see the production of urine in recovery, that's when we can start to relax, then things look good."

Sometimes it can take days before the new organ starts functioning, but in Mr Y's case, it was almost instantaneous. "When it works, I feel good. It is the most rewarding type of operation you can do. It is completely different from the feeling you have after a cancer operation, when the best you can hope for is that everything bad has been removed. This is something positive. You know immediately if it has worked. It is extremely satisfying.

"The speciality that I have the privilege to work in is the most exciting of any others – we are so exposed to the ethical, legal and emotional aspects. We are just immensely grateful to the families because it is extremely difficult to agree to donation when it is so sudden and so unexpected."

That night Mrs X's second kidney is also successfully transplanted into another sick individual. Her death has saved two lives.

Pretty incredible people

Things do not always go so smoothly. In a third hospital, Mrs Z, 53, who has been on dialysis for six years, has been called in at midnight to receive a new kidney. She has had a suitcase packed, ready by her front door for years, as she waits for the correct organ to come up. This is the fourth time she has been summoned; on the three previous occasions tests showed that her body was likely to reject the organ. She is calmly thrilled at the prospect of a transplant, which will free her from dialysis, and will enable her to make a long-postponed visit to her 90-year-old father in India.

She is at the end stage of kidney failure, and finds the thrice-weekly requirement to be in hospital for dialysis profoundly wearing. "Some days you feel depressed. You get emotional, very upset." A surgeon comes in and draws a picture in ballpoint pen of how the operation will be done. "We do it like a plumbing job," he says, explaining that it will take up to four hours. "It looks nice on paper, but it is a major operation. It takes one month to feel OK. Are you OK with that?"

She smiles and says she is. Staff have taken a blood sample to see whether there is anything to prevent the operation from going ahead. "It was very heartbreaking last time."

Later that night, it turns out that the final tests have again shown a strong likelihood that she will reject the organ, and she is again sent home, with no option but to continue on dialysis.

Giving a tour of the dialysis unit at a busy London hospital, the clinical director of renal nephrology explains how exhausting the process is. There are 70 dialysis machines constantly in use here, over three shifts, seven days a week, cleaning the blood, sucking out its toxins, and returning it to the body. The process offers only the equivalent of 10% of normal kidney function.

"They will make light of it but these are pretty incredible people. It is hard work being on dialysis. It takes incredible patience. We circulate blood for four hours, which leaves them tied for four hours to the machine. During that time, we ask their heart and blood vessels to do things that are not unlike a 10-mile run for me. Then they have to go home on the tube, pick the kids up from school or go back to work. These are superhumans for what they endure," he says. "The joy we get when people are transplanted is immense. It is a wonderful thing to see people get better, to see their quality of life go back up."

He is undecided about whether England should follow Wales towards a policy of presumed consent. "Families often balk at the idea of somebody putting a knife to someone they barely think of as dead. I don't think anyone would ever take an organ without consent. We want the public to tell us what to do; we want to know that the public is comfortable with what we are doing," he says.

The assistant director of Organ Donation and Transplantation NHSBT, Anthony Clarkson, mostly wants people to discuss the issue with their families. "We know there is a reluctance to talk about organ donations among families – research shows that half of the population has never had this conversation. There are taboos around death. There is a reluctance to talk about this," he says.

"For the revolution on consent for organ donation in the UK, we need it to become a normal part of end of life care, and we need it to become a normal part of society, where people expect to be asked about organ donation, and the expected response is that they will be a donor. People don't talk about it enough."

Ten days later, Mr Y is still recovering, but has come home after a week in hospital. He is still finding it painful to walk, and is a bit overwhelmed by the quantity of drugs he is required to take, but he hopes he will be well enough to start looking for work again in a couple of months.

He has had a very positive experience in hospital. "It started working straight away. It was amazing. The doctors answered my questions with dignity and respect. They are there to help you to live. The only question the doctor cannot answer properly is how many years the kidney can continue working."

He still has no desire to find out anything about the donor whose organ has freed him from a life on dialysis. "I have the right to ask, but I decided not to. I'm a Christian. I feel it is a gift from God."

Does it feel strange to be living with part of someone else inside? "That is the reason I don't want to know anything about the source. It will play on my mind. I feel if I ask too many questions, I will get too much information. Somebody else's body is in my stomach. Some people wouldn't care, but I mind. I am not so keen to know. It makes me feel sad."

• Join the NHS organ donor register or call 0300 123 23 23

• This article was amended on 10 February, 2014, to correct urethra to ureter.