It is towards the end of my hour with television's Dr Christian Jessen that I finally raise the issue of piles, but from the unflustered, slightly ironic look on his face, you get the sense that barely a day goes by when haemorrhoids are not mentioned. As his fellow Embarrassing Bodies host Dr Pixie McKenna told the Cambridge News recently: "I don't know why people are obsessed with piles, but one of the most common things that gets shouted at us is: 'Do you want to come and look at my piles?' Tis a difficult cross to bear, to be sure."

I mention piles to Dr Christian not because – I hasten to add – they in any way blight my own existence, but because, like much of the UK's TV viewing public, Dr Christian has, over the last seven years, increased my acquaintance with them immeasurably. Thanks to his series Embarrassing Bodies, which returns next month, my mother and I once were gifted with a high-definition close-up of a stranger's anus while we were trying to eat our tea, and I'm sure we weren't the only ones.

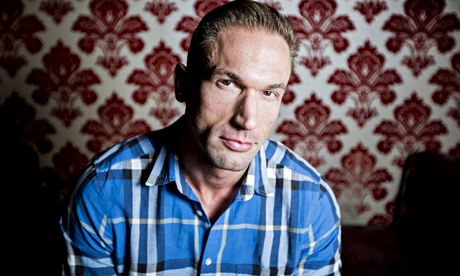

Dr Christian, who meets me at a cafe near the Thames on a sunny Saturday, laughs when I tell him this. "The reason you see it so much on Embarrassing Bodies is because we get it so much," he says. It is, apparently, a problem that affects half the population, but one has to wonder whether or not the British viewing public might be becoming tired of it. Dr Christian thinks not: "When we first filmed it, back when it was called Embarrassing Illnesses and it was a half-hour show, we were filming it in Birmingham, and it was verrucas, piles, eczema. Those everyday GP cases that you see 10 cases of a day, day in, day out, for the rest of your life. I remember thinking, 'This is really dull, this is never going to make a TV show, this is going to be dead in the water after they run the first series.' I'm delighted to say that I've never been more wrong – that the public thirst for medical things, particularly the more gory medical things, is insatiable."

Dr Christian is enormously proud of Embarrassing Bodies, a format that was initially pitched to him as a fly-on-the-wall documentary involving GPs. Not only did it help transform him into the most recognisable doctor in the country, but its format has been replicated in Australia and the Netherlands. It has two Baftas to its name, both of which honoured its website, which, as well as teaching users to perform simple health checks, also features penis and breast galleries that aim to show people the normal anatomical variations that occur.

Before Embarrassing Bodies, Jessen was a sexual health specialist who would make the odd TV appearance to comment on news stories, mainly due to his senior consultant's media-shyness. He did his medical training at UCL, and shared a halls-of-residence corridor with Coldplay, whom he says used to "annoy the crap out of us" by playing their guitars late into the night. He then specialised in sexual health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, with his focus on HIV and malaria leading him to stints in Kenya and Uganda. He now not only fronts Embarrassing Bodies and its spinoffs, but also the equally popular Supersize vs Superskinny. He has also just produced a documentary, Undercover Doctor: Cure Me, I'm Gay, during which he investigates and undergoes a number of so-called "gay cures", which you may have caught last week (it's available on catch-up TV). All this he juggles with magazine columns, his Harley Street clinic, and a voracious Twitter audience who rely on him to answer (and always in capitals) such varied questions as "can HPV get in your eye and lead to cancer?" ("NOT THAT WE KNOW OF, NO") to "will sticking my penis up the hoover (for pleasure) cause any damage to my genetils [sic]?" ("QUITE PROBABLY").

Jessen is seriously buff. Not only is he buff, and bronzed to boot, but he is also charming. Brought up in Hammersmith, west London, he was sent away to school at seven, and has talked of feeling lonely in the first few years, and of being teased, later, for preferring the company of girls to that of boys. His mother is a linguist and his father a physicist. In Cure Me, I'm Gay there is a particularly touching scene in which, having been told by various churchgoing Americans that homosexuality is a product of childhood sexual abuse or trauma, he asks for his father's thoughts. "I was terribly proud of him after filming that. It was unprompted, unscripted", he says. "I wanted to show a dad chatting to his gay son and being completely unfazed by the fact that his son is gay and, in fact, saying the right things like, 'No, we love you all the same', and it was very moving. I was like, no, I'm not going to cry at this point, I'm not going to cry."

This was the first film that gave him full editorial control, and there's no doubt that, for a gay man, the process of making it was extremely upsetting for him – the aversion therapy he undergoes, during which he is made to vomit while looking at homoerotic images, is particularly difficult to watch. "I suddenly went from being how you usually see me on telly, which is as a fairly calm, in-control doctor not flustered by anything, to, I think, being an abused patient", he says. "It's not particularly nice being made to vomit, especially not being made to vomit like that. I was upset for all the people who had to go through this, sometimes enforced, sometimes voluntarily, because they were so miserable and life was so difficult." He tails off, looking thoughtful. "I suspect that, with laws being brought in in countries like Russia and Uganda, they've just taken this massive step back into the dark ages. These sorts of treatments will again start to rear their heads."

When it aired, the documentary trended online worldwide, though not without controversy. The Daily Telegraph wrote than Jessen's "staunch and unflinching homosexuality made him, for these purposes, a bad journalist". Jessen acknowledges this factor. If Cure Me, I'm Gay was biased, he tells me, it's biased in the sense that "I don't want to not be gay – I'm perfectly happy with how I am." Despite being happy and in a long-term relationship, he has had struggles. In the past he's been open about his body dysmorphia, which he links to his own gym-going (it has been reported that he exercises for an hour and a half each day, seven days a week) and that of many young gay men. "Bodybuilding is much misunderstood. I think it comes across as just vanity – worrying about your pecs is just a 'gay vanity thing' – but it's not. It's a far deeper underlying problem than that, and in the case of severe body dysmorphia, it can lead to serious self-harm, in a way.

"I struggled with it for years, and it's linked in to self-esteem, and yes, you do see it very commonly with young gay men. It's sometimes from being teased at school, or being a bit weedy, or a not-being-picked-for-the-team-type issue, but much, much more than that – I'm grossly oversimplifying that", he says. Jessen does this in conversation – he regularly adds caveats to ensure that his point is made as clearly as possible. "All that plays a part in undermining your confidence in yourself, and so how do you tackle that? You develop a false sense of self-image. The way I describe body dysmorphia is that when you look in the mirror, what you see is not really what you are. That's the bottom line of it. With me, when it was really bad, I'd look in the mirror and see the skinny teenager, the beanpole I always was, not the 95kg guy that I had turned myself into. And you can see how that can be very destructive and can turn into steroid abuse, sunbeds, even as far as cosmetic surgery."

Jessen links body dysmorphia to the rise in male anorexia. "The media does have a role to play – images do influence young men in the same way that they influence young women. You can't help but look on the front of some magazine and see a buffed-up film star and feel inadequate," he tells me. This, in part, is why he is so proud of Embarrassing Bodies. A doctor came up to him recently at London's Euston station and made a point about the show that he hadn't previously considered, which is that "you actually show normal bodies on TV". She had a point: elsewhere, there's nary a bingo wing or a spotty back to be seen, but the bodies on Embarrassing Bodies are those that "us lot (doctors) see every day, in all the inglorious ways in which bodies come, and you know, they're not airbrushed perfection, they're not always perfectly formed, or running correctly. It's so important to actually see normal people with normal bodies."

Jessen's other hit show, Supersize vs Superskinny, a programme in which an underweight person and an overweight person swap diets, has faced its fair share of controversy, most notably in 2012 when eating disorders charity B-eat accused it of "triggering" eating disorder sufferers. The reaction to his programmes from the medical profession has been mixed. Half of them, like the "lady doctor" at Euston (I don't correct his use of the term; I'm too dazzled) love Embarrassing Bodies, and say it has made their jobs easier as patients are more forthcoming; the other half have not been so kind. "We get words like 'exploitative', 'freakshow' – they make me so angry, these words. They say, 'You're selling yourself out', 'Go and get a proper job', 'Stop, you're an embarrassment to the medical profession'. You get the full range of things.

"The medical profession is quite slow to keep up with modern technology. We're a very – I want to say stuffy, I'm going to say stuffy – we're a very stuffy profession," he says, emphatically. He feels very strongly that his use of Twitter – and Skype, which he now uses in his clinic – is the direction in which things are moving. "It's nice to interact. It's what we should be doing. I believe in it so strongly because of preventative medicine. You don't let them get ill and then treat them … we just can't afford it within the NHS. What we can afford to do is stop people getting ill in the first place, and one of the best ways of doing that is through social media, through advertising, through television, and through education.

"The NHS", says Jessen, is "a bit like religion. It's the ultimate sacred cow that no one is allowed to criticise or touch, and as soon as anyone tries to make any changes, they become a traitor. Any poor politician who just tries … " He changes track, perhaps aware that he is straying into difficult territory. "It's not going to endure for ever, it can't possibly. It is a fantastic concept, but it has to keep evolving as healthcare keeps evolving, and it hasn't evolved at the same pace."

This doesn't, he hastens to add, mean selling it off to private companies. "I don't know what the answer is. But I think we have to be more prepared to make quite deep changes."

Despite what Twitter may imply, Jessen doesn't have all the answers (though he can tell you what love is: "A TRICK OF YOUR GENES"). But it's clear he cares enormously about his patients – it was a gay patient in distress who sparked the idea for his recent documentary. Dr Christian is also passionate and articulate about many things, including supplements and vitamins, which he denounces, mid-rant, as "charlatanism".

I could listen to him put the world to rights all afternoon, and, while he may not be able to solve the healthcare crisis, dismissing him as nothing more than a TV doctor hardly does him justice. Nor is it fair to reduce his body of work down to piles. As he himself admits: "I know everybody watches Embarassing Bodies and giggles at the willies and giggles at the boobs. That's fine, that's OK. Because at the end of that hour of giggling you will have learned something. Or you may be going, 'Oh my God, I've got that. I might not be going to tell all my friends, but I'm going to go and see my GP.' And if we've done that, then we've done what we set out to do."

I, for one, will be watching the new series, though this time, I'll wait until after tea.