In the earliest photograph I have of us, we are standing either side of our mother, outside of the prefab we lived in. We are three and four years old maybe. I am the smaller. We are both holding letters, probably containing postal orders from our uncle in South Africa. My brother is looking at his envelope with some delight. I am looking at him with some unease and suspicion, as if his postal order was for more money than mine. It probably wasn't. But that was how it felt.

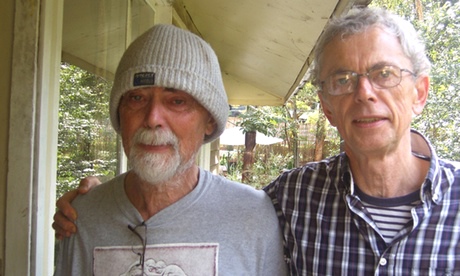

In the last photograph I have, we are side by side, on the veranda of my brother's neglected house in Queensland, Australia. He is wearing a beanie hat to cover the scar from brain surgery and to disguise his hair loss from chemo and radiotherapy. I am trying to smile and he looks distant, as if peering back into the past – maybe back to when we were children outside the prefab and our lives had barely begun.

The next time I saw him, after that final photograph was taken, he was drifting into a coma. He couldn't speak to me but when I squeezed his hand, he responded, and he smiled slightly and he fell asleep again. I spent the next week with him, watching him die.

I had a call from my brother one morning 18 months ago. He had been in Australia for more than 30 years and had had two or three enduring relationships, but now lived alone. We had never lost touch, though sometimes our contact was sporadic. But he had been over to visit and we exchanged calls and cards, and he sent his nephew and niece presents for their birthdays.

The tenor of his call was that he was worried. He was experiencing problems in reading and remembering. I thought he might have had a mini stroke and advised him to get a scan. He turned out to have a massive brain tumour. He was immediately operated on and I flew over to be with him.

You expect to look after your children when they are young, and maybe half expect to care for your parents when they are old, but siblings are another matter. You assume that they will look after themselves or, if they won't, someone else will – their partner, or offspring, or somebody. But not you.

My brother was a kind but difficult man – difficult in person and difficult to describe. He was highly educated and very intelligent, but he had an almost self-destructive streak, a kind of seeking after a non-existent, unattainable perfection which meant that if things couldn't be entirely right then it was better that they be entirely wrong, as that was preferable to mediocrity and compromise.

He was bright and hard working. If he didn't come first in every single subject in the class, he got upset. He and my mother would talk late into the night about his prospects, of academic distinction, of university, of high-flying, well-paid jobs.

Being less intelligent and naturally indolent, I rebelled. As nothing seemed to be expected of me, I did my best to do as little as possible. But due to our father's early death, my elder brother felt responsible for me. I can still remember him trying to pull me out of bed one Saturday morning, because I was supposed to play rugby for the school team and had decided not to go, as it looked a bit cold and wet. He was furious. But, in fairness, I did try to brain him once with a cricket bat.

Yet, most of the time, we got on well together. Our father's death brought us close. We seemed like an island sometimes, my brother, my mother and I. We were flooded out of our rented accommodation and given a small council house on a tough estate. We went to a Catholic school a few miles away and wore different uniforms to other kids. Each day was like running a gauntlet and we often had to fight with somebody on the way home.

Sure enough, my brother went to university, to Imperial College London, to study chemistry. He could solve any problem you gave him. But when there was no one to give him a problem to solve, that, maybe, was where his subsequent problems arose. I had my suspicions about his practicality from early on. As a schoolboy, he developed an interest in astronomy. But he couldn't just buy a telescope, he decided to make one and to grind his own lenses. Two pieces of glass arrived, three feet in diameter and about five inches thick. After about an hour's grinding, the glass was as flat as ever. But it was a long time before he gave up and admitted defeat.

When I got over to Australia, I found someone who was half a stranger. The brain surgery had affected his thought processes. His house was a tip and he had a beard like Ben Gunn. Frankly, he looked like a vagrant, but was quite unaware of it.

My daughter was also, coincidentally, there at the time, passing through Brisbane as she backpacked around Australia. She was wonderful with him, though she barely knew him. She took him to the shops and to the bank and out for coffee. She told me that he would tell complete strangers about his tumour and his eyes would fill with tears.

She moved on and we were left together. I tried to tidy the place up and in doing so threw out my brother's old hob kettle, which was hazardous, as it had no handle. I bought him a smart new one, but when he found the old battered one gone, he was upset. I realised that his and the kettle's identity had somehow fused; they were of the same era, same vintage, they shared a lot of history. I had thrown his past out. I felt terrible.

I was in Australia for two months. Initially I deeply resented the role of carer that had been forced upon me, but gradually I felt less aggrieved and began to enjoy being able to help him, to drive him around and to take him to his hospital appointments and to wait while he had radiotherapy.

We went out for meals with his friends; we went on a cruise down the Brisbane river; we went out cycling a couple of times and there were moments of hilarity as we reminisced about our mother's home-made mutton soup, which you had to eat fast, before the fat congealed on top. Or we would enjoy watching mindless shoot-em-up DVDs on his television.

But the surgery, the chemo, the radiotherapy were to no avail. The tumour grew again. My brother collapsed and was taken back into hospital. He slipped into a coma. He died in the hospice a week later. I was with him, sleeping on a camp bed in the corner of his room. I wondered what had woken me. It was the silence. He was no longer breathing.

I think of him a lot, several times a day. I was glad I was with him at the end and glad that I went over when he fell ill.

LP Hartley wrote, "The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there." My brother was the only other person in the world who knew that country – the one that he and I had lived in as children. Now he has gone, there is no one else to remember it. Just me. I can recall us lying on the living room floor, in paroxysms of laughter, the way children get sometimes, our parents staring at us, perplexed about what was so funny. We probably didn't know either. We just went on laughing, each setting the other off again, laughing until we ached.

There are many ways to remember somebody you have lost. I think that's the one I'll choose.