The health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, whose knowledge of medicine stretches almost as far as David Cameron's knowledge of jellied eels, would like NHS surgeons to stop performing "purely cosmetic work" on patients. He thus faces a face-off with facial surgeons – for they know, as I do, that there is no such thing. Cosmetic surgery, like racism, is never purely skin deep. One wonders of course whether the long list of Conservative MPs with financial interests in private health, which feasts on unregulated cosmetic work, may have applied pressure here, but let us be charitable and assume Hunt is capable of "purely" independent thought, devoid of agenda. He is right to highlight the financial pressures on our health service. Yet, like an idiot on a sun bed, he grasps short-term gain in denial of long-term damage.

I have twice lain in hospital while NHS surgeons took to my face – paid for entirely by taxpayers. The first occasion I was 18, two years after I went to my GP and told her my protruding ears, sticking out at 90 degrees, were troubling me. I was suffering from depression and, what I now know to be body dysmorphia, and had been receiving counselling since I was 14 to deal with these. Psychotherapy has limits. I know this because after four years of it I still couldn't stomach my appearance, and after one simple procedure, and a fetching week-long turban bandage, I felt transformed. No single event in my life has so boosted my self-esteem. My relationship with my reflection became manageable, even positive at times. I did not need further therapy to be able to cope with mirrors. How much might that have saved the NHS in cognitive behavioural therapy or psychodynamic psychotherapy?

On the second occasion, two years later, I had been brutally attacked in my home by burglars who beat me to a blood-soaked pulp (realising I was gay fuelled their violence), one wound from which was my teeth cutting through the left side of my face. At A&E they could have simply grabbed a passing doctor to sew me up, but instead they suggested I return the next day when a plastic surgeon would be on duty. He did a beautiful job, bringing the two flaps of my cheek together with expert precision. Now when I look in the mirror I cannot see a victim, and I cannot see the hate my attackers attempted to brand on to my face. Again I would urge Hunt to think of the long-term savings in NHS psychotherapy. He does at least acknowledge "there will be times when there is a mental health need" for NHS cosmetic surgery. As such, more people should be offered it, not fewer.

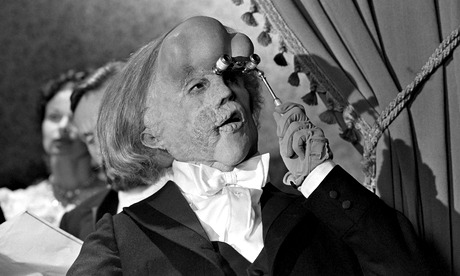

Last month I went to Ethiopia with the film actor John Hurt, famed for his role in The Elephant Man – about the egregiously disfigured Joseph Merrick – to report on the work of a British charity called Project Harar. Each year it sends a team of NHS surgeons – during their annual leave – to Addis Ababa to perform operations on young people with severe facial disfigurements. These can be cleft palates, grapefruit-sized tumours, noma (holes in the face from a bacteria prompted by malnutrition), or scarring from animal attacks. I expected to be most horrified by the extreme distortions and protrusions. What struck me, and my companion who is the charity's patron, however, was the visceral isolation emanating from patients. Children were shunned for being different, for being deformed, kept inside as it brings "shame" on the family, locked out from schools, denied friends, sometimes sent into the wilderness, believed to be demonic.

When I clasped the hand of one young woman who had had a large tumour removed from her cheek, she squeezed my fingers with such cautious excitement, and then with such relief to simply be touched by another human being that it reminded me, starkly, once again that there is no such thing as "purely" cosmetic, skin deep. Our looks, judged now more than ever, and in the west even more so, matter just as our physical health does. And to deny this, to deny the social, psychological, even financial implications (good-looking people earn more) of our faces is to be blinded by the resulting impact on our health and welfare services. The ugly reality, Mr Hunt, is staring you, and all of us, in the face.