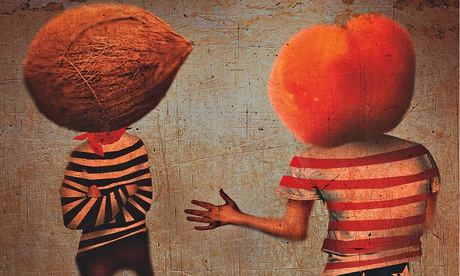

Erin Meyer, an American management professor living in Paris, tells the following mildly excruciating story about attending her first French dinner party. To break the ice, she brightly asked the host couple, "How did the two of you meet?" You can almost hear the mortified silence. Asking a French stranger that question, her (French) husband later explained, was "like asking them the colour of their underpants". As Meyer explained recently on the Harvard Business Review website, she'd fallen into a trap first identified by the psychologist Kurt Lewin, who divided the world's cultures into "peaches" and "coconuts". Peach people are soft on the outside, immediately friendly and familiar, but if you mistake that for real intimacy, you'll soon hit the hard stone that protects their inner being. Coconuts have tougher exteriors, but get past that and they're sweet inside. Americans, according to stereotype, are peaches; the French, like the Russians and Germans, are coconuts. Meyer's faux pas was a case of the two messily colliding.

Like any attempt to split humanity neatly into two, the peach/coconut divide is absurdly oversimplified. But it's also useful. The Dutch organisational theorist Fons Trompenaars, who popularised it, argues that it explains all sorts of animosities that bedevil cross-cultural friendships, business dealings and diplomacy. Coconuts view peaches as insincere, because their surface effusiveness doesn't signify deep friendship; peaches see coconuts as rude, refusing to oil the wheels of life with a few pleasantries. It's all relative: the British are coconuts in California but peaches in Paris. And there are subtle gradations, as caricatured in the old joke about the Swede and the Finn who meet for drinks, spending hours imbibing schnapps in silence. Eventually, raising his glass, the Swede says, "Skol!" The Finn is appalled: "Did we come here to talk, or to drink?"

Still, it's odd that cross-cultural misunderstandings retain their power to offend. We live in a hyperconnected world; even if we're annoyed by Those Other People, why also feel insulted, instead of just chalking it up to different customs? Why, in 2014, can an American still genuinely offend a Brit by not buying a round, or a Brit a South Korean by handling his business card too casually (I speak from experience)? Partly, Trompenaars shows, it's because each side's value system is logical, yet seems to render the other's downright crazy. In one survey, he asked people if they'd lie for a friend whose driving got him in trouble with the police. Most Swiss wouldn't dream of it: how can society survive if you can't trust people to tell the authorities the truth? Venezuelans disagree: how can society survive if you can't trust people to stay loyal to their friends? "Both logics are logical," Trompenaars says, which is one reason multinational firms that try to impose woolly corporate values on their workers – "integrity", say – are surprised to discover it doesn't work.

"The opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth," the physicist Niels Bohr is supposed to have said, which is one of those observations that applies to more areas of life the more you ponder it. The peach/coconut distinction is no exception. Is it best to be warm with people you barely know, or to save your warmth for meaningful relationships? The only right answer is that there isn't one.