This was supposed to be a piece about contemporary reservoirs – shiny, modern pumping equipment that looks like part of the latest Star Wars film, bucolic views across a stretch of water big enough to be an inland sea, the sound of exotic birds diving for fish and a gentle, fragrant breeze to bring cooling relief from the heat-wave sun.

Why my editor didn’t go for the idea, I will never know. Instead, she decided I’d have a far better time spending one of the hottest days of the year down a south-London sewer searching for a fatberg. No, it’s not someone from the latest voyeuristic TV programme about Americans struggling with their weight, it’s a hard, putrid mass grown from the congealed fat, oil, wet wipes and other sundry food and health products chucked down plugholes by households and restaurants, from kebab houses to some smart hotels that should know better. “They can lead to collapses in the sewers and sewage erupting from manholes,” says Becky Trotman, a Thames Water spokesperson.

An increasingly frequent menace in Thames Water’s 68,000 miles of sewers and other systems around the country, these grease balls are blocking Joseph Bazalgette’s engineering masterpiece, which was designed to save London from the 19th century’s big stink, not the 21st century’s big burger. Not McDonald’s burgers, funnily enough. The company is a good guy in this piece, sending 600,000 litres of used cooking oil from its restaurants in London every year to be converted to biodiesel to run half its lorries. Too many other people fail to follow suit. The resulting toxic mess helped to create a 15-tonne monster fatberg in Kingston upon Thames this time last year and now there’s one blocking the effluence beneath the tarmac on the New Kent Road, near Elephant & Castle. Wonderful as the Victorian system is, it was not designed to cope with the numbers of people living in London today or really anything other than what you’d expect to find down a sewer – water and excrement.

The fatberg is in one of the main (or trunk, to use the correct description) sewers. They’re the ones into which the smaller tunnels drain. Smaller sewers in the capital are about 10-20cm in diameter, as are many of the main sewers outside the capital in cities such as Oxford, the centre of which was shut down by one of the grease globule invaders earlier this year. It has to be a big lump of lard to block a London trunk sewer, which can be big enough for a person to walk through.

We meet at Greenwich pumping station at 9.30pm, because an earlier visit to the manhole is impossible thanks to traffic. It’s a quaint station that used to have a garden and gardener back in the pre-privatisation days of the Water Board before 1989. Now there’s a car park and a large easy-maintenance fishpond with koi carp, probably not something that many of Thames Water’s 15 million customers would expect to see at a sewer plant.

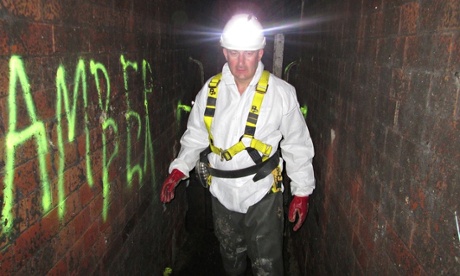

Health and safety paperwork read and signed – gas, explosion and collapse risks make it dangerous underground – we head off in a large van. There needs to be plenty of room for everyone to change into the CSI-style suit, hard helmet, surgical topped with heavy-duty gloves and thigh-length wellies for protection from the dangers down below.

There are eight in the team and on arriving at the New Kent Road manhole we don our protective clothes. It takes two attempts to find the right access point. Sometimes it’s not so easy and technicians have to go a long way underground to find what they want. “I’ve been 2,000 metres,” says 38-year-old trunk sewer inspector Mitch Fraser. Not today though, surely? “No, we won’t be doing that now.” Relieved, I realise that I am now actually looking forward to the visit despite my fears. The team, just a few of the workers saving UK cities from a noxious drowning, are so knowledgeable and passionate about the subject. Rose can’t praise them enough. “We have to get people out to every part of the capital,” she says. “It’s remarkable that it costs only £1 a day for each customer.”

A gas detector is lowered into the hole and we must then wait for five minutes to ensure there are no dangerous fumes. Methane is the main problem, and, in case we encounter gas unexpectedly, we are issued with a Turtle, which will enable us to breathe if we run out of oxygen.

Gas clear, I am climbing down a ladder into a manhole hooked to a safety harness to catch me if I fall into the dank blackness. As my hands sweat into the plastic surgical gloves and my boots squelch into something at the bottom of the ladder that I’d rather not describe, our headlamps illuminate the glorious interior, one of Bazalgette’s finest. Near-perfect brickwork in the tunnel, just high enough for me not to bang my head, creates a corridor leading into the dark. Water can be heard gushing in the distance, about as close as I’m likely to get to the reservoir story. Tough on the nose? Yes there is a definite toilet smell, but there’s also a hint of detergent and toothpaste, which is what you’d expect, according to trunk sewer technician Tony Gillham (usually called a 'sewer flusher' in the old days). “Most of the water down here is from rain, showers or washing machines,” he says, wandering up and down knee-deep in wastewater as relaxed as a seaside holidaymaker paddling.

As we move forward, Gillham bumps into something on the ground. A rat? There are thousands of them down here, although they run away as soon as anyone approaches. No. The obstruction looks like at a large piece of kerbstone granite. “How did this get here?” he shouts over to Eddie Thomas, 56, who doesn’t know the answer, but nothing surprises him after his 25 years of service. “I’ve seen a dead body, bike parts and lots of syringes, especially around Leicester Square where there are loads of junkies. One of our men got a needle in his leg and had stomach problems for years afterwards. There’s even furniture. I once saw a settee.”

Perplexed by the presence of such a large object in such a confined space, I follow as we walk to a sophisticated chamber, several other tunnels and the sewer itself, which is bordered by a weir, over which the water drains into a storm tunnel in heavy rains or when the main route is blocked. The storm tunnel carries the overflow into the Thames, an increasingly frequent occurrence and something the planned Thames Tideway Tunnel aims to prevent.

Crouching down, it’s possible to enter the trunk sewer to find the fatberg, but after a few minutes of searching it doesn’t seem to be there. “It must have been flushed away by the torrential rain we had yesterday,” says Gillham. Global warming unblocking the sewers? Perhaps. “But here’s another smaller one, which might grow if we left it.” He rips a greeny-white oozing pustule from the wall just above the water line. “There.”

Yes, the almost natural world of the reservoir is tempting in the blazing sun, but then, oddly, so are the sewers. As Thomas says: “In the winter everyone wants to go down because they’re warm, and in the summer everyone wants to go down because they’re cool.” A hard night’s work, indeed. Anyone for a kebab?

Interested in finding out more about how you can live better? Take a look at this month's Live Better challenge here.

The Live Better Challenge is funded by Unilever; its focus is sustainable living. All content is editorially independent except for pieces labelled advertisement feature. Find out more here.