In 33 years of the Aids pandemic, which has perhaps caused more shock and anguish than any other infectious disease since the black death, only one person has ever been cured. That man was "the Berlin patient", now identified as Timothy Ray Brown, an American treated in Germany, whose case was publicised in 2009. Until last week, the world hoped that a small child had joined him, but the Mississippi baby, now nearly four years old, is back on antiretroviral drugs after two tantalising years when regular tests failed to find any trace of the HIV virus in her body.

At the International Aids Conference that opens in Melbourne, Australia, on Sunday, the relapse of the Mississippi baby will figure in much of the conversation on and off the platform. Drug treatment, now reaching nearly 13 million people, has stabilised the Aids epidemic in most countries, but it is expensive, and may be unsustainable because it requires huge efforts from overstretched health systems, especially in developing countries. Death rates are reducing – around 1.5 million last year – but while new infections have dropped by more than a third since 2001, when there were 3.4 million, still two million people are infected with HIV every year. Increasingly, Aids is becoming a bigger issue in marginalised populations who are harder to reach and may live on the fringes of their societies – sex workers, men who have sex with men in countries such as Uganda, where homosexuality is not tolerated, and drug users in eastern Europe.

Attempts to create vaccines over the last three decades have proved fruitless. In 1984, when the virus was identified, Ronald Reagan's upbeat head of health and human services, Margaret Heckler, predicted a vaccine within two years. Vast sums of money have gone into trials of different candidates, but in spite of the occasional burst of excitement, none has been shown to work effectively enough. The latest piece of hopeful news came last September, when scientists said they had managed to protect nine out of 16 rhesus monkeys with a vaccine – but trials in animals have previously shown good results that did not translate into protection for humans.

So scientists in the last couple of years have rallied around a new flag – that of a cure for Aids. Brown and that nameless little girl in the deep south of the US show just how difficult to achieve that will be.

Brown was the exception that proves the rule. In 2006, having been HIV positive and on treatment for over 10 years, he was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia. He needed a bone marrow transplant to replace his own cancerous cells with stem cells that would remake his immune system. His doctor, Dr Gero Hütter, at the Charité hospital in Berlin, was able to find him a very special and unusual donor: somebody who was naturally resistant to HIV infection due to a genetic mutation that blocks HIV from entering the cells in the human body.

Brown had two stem cell transplants from the donor, in 2007 and 2008. The HIV virus disappeared from his body and it has been undetectable ever since.

Stem cell transplants, though, were never going to be the answer. They are difficult and potentially dangerous for the recipient, and only undertaken where they could save a life. It was Brown's cancer that threatened his existence and justified surgery, not HIV. Hopes, however, were cautiously high when two other men with HIV and cancer – duly nicknamed "the Boston patients" for the city where they were treated – also underwent bone marrow transplants, one in 2008 and one in 2010. In July 2013, their doctors said they had both stopped their drugs, one for 15 weeks and one for seven, and had no detectable virus in their blood. They may have been cured, the doctors said. Six months later it was announced that the virus had returned. The lucky break for Brown had been to find a donor who was both compatible with him and resistant to HIV infection – an incredibly rare combination. The Boston patients were not so fortunate.

But still there was the Mississippi baby. She was born in 2010 to a mother who had never attended an antenatal clinic. Nobody knew she was HIV positive until she was in labour. Dr Hannah Gay, the paediatric HIV consultant at the Jackson Memorial Hospital, took an unusual decision. Without waiting for the tests that did eventually confirm the baby had the virus, she put her on a strong course of antiretroviral drugs. The baby was on treatment within 30 hours of her birth and stayed that way until the hospital lost contact with the mother 18 months later.

When mother and child reappeared five months later, the baby had no detectable virus in her blood. The case, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, caused huge excitement in the scientific and campaigning HIV world. A new hypothesis was born – that hitting the virus very early in the infection might somehow prevent it taking hold. It seemed plausible. A second baby was treated in California within four hours of birth and is still on the drugs.

When the announcement came that, two years on, the Mississippi baby's virus had re-emerged, some called it a disappointment, some a setback, while others insisted it was part of a learning curve. HIV scientists have learned to be resilient and to guard against false hope, but there is little doubt that the mood of the Melbourne conference will be a little less upbeat because of the news. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in the US, said: "Certainly, this is a disappointing turn of events for this young child, the medical staff involved in the child's care, and the HIV/Aids research community. Scientifically, this development reminds us that we still have much more to learn about the intricacies of HIV infection and where the virus hides in the body." His institute, at the forefront of HIV science, "remains committed to moving forward with research on a cure for HIV infection".

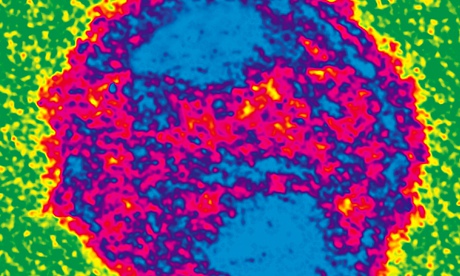

HIV, as the vaccine researchers know to their cost, is as formidable a foe as science has ever encountered. It is able to hide itself in the body where highly sophisticated modern testing cannot find it. Every time it seems that drugs have coshed it out of existence and the treatment is stopped, it reappears. There are reservoirs we cannot detect.

Dr Sarah Fidler from Imperial College London is one of the HIV researchers involved in the hunt for a cure. She is working on a trial, due to start next year, which will endeavour to trick the virus into emerging from its hiding places and then trigger the body's immune system to recognise it and attack it.

In spite of all that was said, nobody could be completely sure that the Mississippi baby had ever been free of the virus, she says. HIV inserts its DNA into the patient's cells. There was no active virus, but there were traces of the virus's DNA. You don't know, she says, whether it will actually be expressed as "real-life virus", especially with a baby, because you cannot take big enough blood samples for the necessary tests.

"For some of the blood tests you are taking 300ml from an adult", she says. "There might be one in a million or one in 10 million cells that have virus in them."

The announcement from the US is, Fidler says, "a very big disappointment". But she still found it surprising that the viral levels in the baby remained as low as they did during the time she was not receiving treatment.

She thinks that very early treatment could perhaps help knock out the virus, but there are practical difficulties even with babies, let alone adults. To treat babies within hours of their birth – which is when they become infected – you need to have the drugs available whenever and wherever the delivery of somebody with unknown HIV takes place, which could be at home. Adults may not know when they have been infected – and if they do, are unlikely to race to the hospital within hours.

Next year's trial to flush out the virus and prompt the immune system to recognise it is a big collaborative effort, involving five leading British universities and funded by the Medical Research Council. Around 50 volunteers, all recently infected with HIV, will take drugs until the virus is almost undetectable, and then be given a drug – normally used in cancer treatment – to make it reveal itself. They will also receive a therapeutic vaccine that will help the immune system recognise the virus. It is an approach that has been called "kick and kill".

Fidler says she does believe there is progress towards a cure. "I think we have a much better understanding of the virology and the immunology. There's a lot of in-vitro [test tube] work."

There is more than one accepted definition of "cure" in the Aids context. Experts at the International Aids Society, the organisers of the Melbourne conference, talk of a "sterilising cure", where HIV is eradicated from the body, as they hope has happened in Brown's case; and a "functional cure", where HIV remains at a very low level without progression. That is the situation with the "Visconti cohort", a group of 14 people in France who were given drugs very early, within a few weeks of becoming infected (normal practice used to be to wait until the patient's immune system began to be depleted) and have been closely followed ever since. They stayed on treatment for three years, on average, and then stopped the drugs. After around seven years, the amount of virus in their blood remains very low and their immune system is working well. They are said to be "functionally cured", although experts cannot be certain they are not people who would never have become seriously ill anyway. There are people termed "elite controllers" who, apparently for genetic reasons, can be exposed to HIV infection and never become ill. Those include a group of women working in Nairobi's red light district who have been frequently exposed to clients with HIV and yet have not developed it themselves.

Some of the best news in recent years has been that the antiretroviral drugs to keep the virus at bay can also protect the partners of people with HIV. Because they depress the viral load to almost undetectable levels in a person with HIV, it is highly unlikely it can be passed on. It follows that the more people around the globe we can get on treatment, the fewer new infections there should be. The drugs can also protect people without HIV who are having a sexual relationship with somebody who is infected. The World Health Organisation last week strongly recommended that men who have sex with men consider taking the single daily combined drug pill as a means of protection.

There is plenty of reason to celebrate the achievements of the last 33 years, and plenty of hope for the future, so this week's conference will not be a gloomy event. The pandemic can be controlled, that much we know. Whether a cure – functional or otherwise – is possible is hard to say, given last week's news. But the scientists heading along that path are determined to give it their best shot.