The early stages of my doctoral research were marked by an intense and heady mixture of anticipation, excitement and gratitude. While the first two disappeared fairly quickly, the third never did. In fact, by the final stages of my PhD, the only thing mixed in with the gratitude was relief. Handing in the thesis, passing the viva, even graduating – there was so much relief that there was barely any room for enjoyment.

Anyone who has done a PhD will be familiar with the kind of journey that I have described, but there is something else which, in my experience, affects a great many PhD students – and particularly, if by no means exclusively, those working in the humanities – and yet is not often talked about: isolation.

All PhDs are solitary affairs

When you carry out doctoral research you are, by definition, the only person working on the precise topic of your thesis. There will be others whose research is closely related to yours, but nobody else is doing quite what you are doing. In this sense, all PhDs are solitary affairs.

Doing your doctoral research in the humanities, though, tends to be a particularly solitary experience. If your PhD is in the sciences, it will typically involve spending most of your working time in a lab. You'll be surrounded by other people, people with whom you'll have lunch and share coffee breaks; you'll talk to them about your research, about their research, about the person who keeps breaking everyone's equipment, about the problems of booking a centrifuge, and – far more importantly – about all of the things that human beings talk about when they're not talking about work.

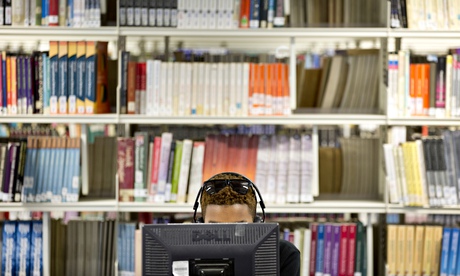

If your PhD is in the humanities, then you'll tend to work at home, in the library, or – if good facilities are available – in your faculty or department. Wherever you do choose to work, you will tend to work in solitude, because the nature of the work demands it. You'll go to one or two seminars or lectures a week, but not much more than that.

Why is isolation not often talked about?

You will, of course, arrange to have lunch or coffee with friends, but it's unlikely that you'll develop a routine of doing this more than a couple of times a week. You'll join or create reading and study groups, but these will tend to offer a pleasant distraction from your research rather than a means of developing it. On an average working day, you may not speak to anyone at all until the evening, unless it's to ask a librarian about the intricacies of a particularly bizarre cataloguing system.

Those who do PhDs in the sciences are often horrified by how mind-bogglingly solitary the final, writing up stage proves to be. But a PhD in the humanities can often resemble one long, three-year (or, realistically, four-year) writing-up process. Routines can dissolve entirely, and with them the divide between work and non-work.

None of this is to suggest that doing doctoral research in the humanities is harder than doctoral research in the science. Doing doctoral research in the sciences comes with its own, very different problems – in many labs there can be an unhealthy competitiveness and, as in any workplace, a culture of bullying – but one of the biggest problems involved in doing a PhD in the humanities is just how solitary it is.

This is something that is not widely acknowledged, and it is something which many prospective doctoral researchers aren't aware of or prepared for. I was lucky throughout my doctoral research to be surrounded by an extraordinary group of friends, and I also had a very supportive supervisor. Yet many doctoral researchers are not so fortunate, and this is something that we do not talk about enough.

Solitude can easily become isolation

Solitude, of course, isn't necessarily a bad thing; not only is it necessary much of the time, but it is also highly desirable much of the time. However, solitude can easily become isolation, and many people doing doctoral research – particularly, although not exclusively, in the humanities – end up feeling completely cut off from humanity.

Prospective PhD students need to be aware of what they are getting into, and of the practical steps they might take on an individual level to prevent solitude from slipping into isolation.

But universities keen to recruit PhD students must ensure that appropriate networks are in place to support those students. While every PhD student rightly expects to receive academic support throughout the duration of their research, many – those in the sciences included – feel that they are not offered any pastoral support, or that they don't know where to go to seek it.

At a time when the prevalence of mental health problems in academia is only starting to be identified – and we really are just beginning to scratch the surface – we need to start talking about the sense of profound isolation experienced by many doctoral researchers.

Five tips on how to survive a PhD in the humanities

1) As far as possible, don't work at home. Whether it's in the library, in your department or – if you're really lucky – in an office that has been provided for you, find a space in which you can be productive and commit to using it. Stick to a routine – working a nine-to-five day (or, realistically, a nine-to-seven day) somewhere outside the home is the most obvious but also the most effective way of separating work from non-work, a major problem for many PhD students.

2) Make coffee with friends part of your working day. But don't spend the entire time talking about work.

3) Go to conferences, and give papers at them. It's a daunting prospect at first but presenting your work, getting positive feedback on it, and meeting people who are working on similar topics at other institutions is all invaluable, both professionally and psychologically.

4) Join, or create, a writing group. In the early-to-middle stages of your PhD it can be helpful to be part of a small group (generally made up of people working in the same discipline) who read each other's chapters and then meet weekly or fortnightly to discuss them. This is a good way to get constructive criticism from someone other than your supervisor and, perhaps even more importantly, it makes you aware that you're not the only person facing difficulties with writing.

Bear in mind, though, that in the final stages of your PhD – when the pressure is really on – having to read chapters of other people's theses can become a serious distraction to the writing of your own.

5) Don't confuse stress (which is normal) with hating your PhD (which isn't). Many fall into a largely unconscious but very dangerous trap of finding themselves in competition with their peers to see who can be the most negative about their own work. You started your PhD because you cared about it. Try to retain a sense of why it's important, both to you and – in its own, small way – to the world.

Michael Perfect works in the fields of 20th/21st century literature and postcolonial studies. He has taught at the University of Cambridge, where he obtained his PhD in 2011. His book Contemporary Fictions of Multiculturalism will be published later this year.

Can you relate to this piece? Share your experience of studying for a PhD and offer any tips for how to combat loneliness in the comments below.

Join the Higher Education Network for more comment, analysis and job opportunities, direct to your inbox. Follow us on Twitter @gdnhighered.