"I once broke my leg in 10 places. As I was taken to hospital, someone shut the door on my leg. You can imagine the pain. But I can tell you the pain of depression is many times worse." This powerful quote from businessman Dennis Stevenson illustrates how mental pain can be just as real and even more agonising than physical pain. It opens a punchy polemic that demands action to tackle the misery of mental illness, pointing out the strange inequality that sees broken bones treated but shattered spirits ignored.

Many readers will know this from personal experience. One in six British adults suffers from depression or anxiety disorders that disrupt, even destroy, lives. Mental illness is often more disabling than chronic conditions such as angina, arthritis or diabetes, while it shortens life expectancy as severely as smoking. One in three families contains someone who suffers mental illness, with one in 10 children having diagnosable mental disorders – yet fewer than one-third of these people receive treatment.

Such shocking statistics litter the pages of Thrive, the latest blast by former "happiness tsar" Richard Layard in conjunction with David Clark, professor of psychology at Oxford University. Lord Layard is a celebrated labour economist who deserves plaudits for promoting the concept of placing wellbeing alongside wealth as a government goal – an idea promoted by David Cameron in opposition, then sadly shunted aside in office after coming under fire from critics who failed to understand the issues.

The book's central point is that the failure to place mental illness on a par with physical illness costs the country dearly. This is perhaps most obvious with suicide rates. The vast majority of people who kill themselves are mentally ill – and as many people die worldwide at their own hand as from murder and warfare combined. Twice as many men take their own lives as women, something I have seen from traumatic personal experience like too many people – and perhaps most poignantly, youth suicide is rising in most nations.

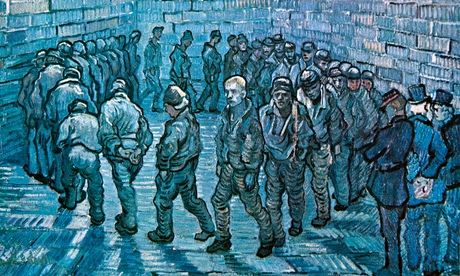

Beyond these individual tragedies, the authors argue, the entire country suffers from this mental health crisis since it imposes such costs on society. "The scale of mental illness is mind-boggling," they write. It accounts for almost half of absenteeism, keeps big numbers out of work and drives up the benefits bill; the combined effect on the economy reduces national income by an astonishing 4%. Nine out of 10 prisoners also have mental health conditions upon entering prison.

This barrage of data is bad enough. "But what is really shocking is the lack of help," say Layard and Clark. It may not make for the most scintillating reading but it is hard to argue with their case that the failure to help those in mental distress is an injustice. Anyone with the slightest experience of mental illness knows how crushing these conditions can be; we should be thankful that the courage of some sufferers, in discussing the impact in public, is starting to end an irrational social stigma. It also makes economic sense, since helping people to recover from their problems generates immense savings for national economies.

If there is a flaw, however, it is their promotion of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). Clearly the treatment has a crucial role to play and the pair deserve credit for ensuring it is more widely available in Britain after proving to politicians that it is supported by scientific evidence. But while it can be more effective than swallowing drugs and gives back to people some control over their lives, it does not necessarily solve underlying problems, prompting concerns it sometimes offers a sticking-plaster approach.

Additionally, some of that evidence they proclaim in the title seems slightly rudimentary. A randomised trial of the employment effects of CBT in Britain is referred to more than once but it involved two groups of just 150 patients each, which means the 21% improvement rate attributed to the therapy amounted to 32 people after four months, surely too flimsy a study to bear such weight of argument. But these are minor quibbles for what is otherwise an important contribution to one of the key health issues of our age.