Science regularly delivers brilliant insights that stretch understanding and reveal new worlds. Then again, it sometimes produces "insights" on the order of "people like eggs because eggs taste good", or "the sun cheers everyone up" – banal or tautological statements given a fresh sheen of authority by experimental data.

Some recent research on the kind of art that works best to cheer patients in hospitals is of this less-than-earth-shattering nature. Well-heeled US hospitals that decorate their corridors with cool contemporary art claim a scientific basis for their decor. They cite studies revealing that – guess what – patients are more likely to be cheered up by landscapes and soothing colours than by terrifying expressionist battle scenes. For example, one study concluded that "images of fearful or angry faces" should be avoided in hospital art. On the basis of such research, one American hospital that says it selects art that is "not disturbing, but uplifting and diverse".

I think two things are unhelpful about this supposedly scientific approach to the use of art in hospitals. First, the conclusion that happy art is more helpful than sad art is utterly banal and simply backs up common sense. And second, common sense may need challenging here as elsewhere.

The scientific field of neuroesthetics – which explores the biological basis of artistic experience – is quite new, but it has already advanced beyond the trite conclusion that nice art creates nice moods. Professor Semir Zeki of University College London, a pioneer in the field, examines difficult and complex connections between art and neurobiology. While Zeki believes strongly that the need for beauty lies deep in our biological nature, he is also interested in why we can respond – as we clearly can – to art that is not "beautiful" at all. For instance, he recently wrote of his appreciation of Tracey Emin's My Bed as a work of art that represents depression.

It seems to me that a rich approach like Zeki's is far more helpful than simplistic research that "proves" an image of a green tree is more likely to induce happiness and optimism than, say, Munch's Scream might do. Isn't there something patronising and untrue to the human condition in this urge to fill hospitals with jolly art? I remember accompanying my father for a medical test in part of an NHS hospital decorated with a bright mural of clowns and birds. It really didn't help. Why assume that all patients have infantile minds? Why assume that infants do?

There is another kind of evidence that may help to understand how art can help in facing illness: researchers should consider art history as well as neurology. Before the birth of modern medicine, hospitals could offer little in the way of actual cures. Even basic concepts of hygiene were beyond them. What medieval hospitals could offer was solace, and they often provided this through art. What worked for them?

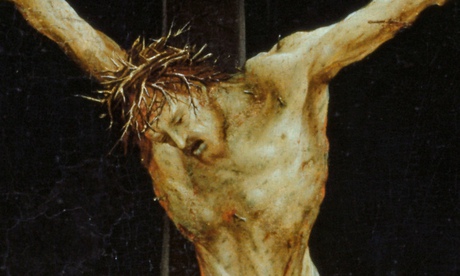

In a hospital monastery at Isenheim near Colmar in 1512-16, the German artist Matthias Grünewald painted a multi-part altarpiece that depicts the passion of Christ with disturbing intensity. Grünewald shows Christ rotting on the cross, covered in terrible scabs. It is a nightmare vision but probably looked familiar to patients, who often came to this monastic establishment to be treated for the ravaging disease ergotism. In later panels in his narrative, Grünewald does offer hope: his sick Christ is resurrected in bodily perfection and a brilliant spiritual light. Suffering leads to renewal.

Grünewald offers hope and bright colours – but he also portrays pain. To me, it seems that such realism matters if hospital art is to mean anything. Fantasy is fake: the mind knows that. Subjecting the patient to kitsch joyous propaganda that is transparently false may therefore incite despair. A sense of truth is the most powerful thing in art, in hospitals or anywhere else.